Yelling, chaos, arguing. The dinner-table dynamics play out like warfare, insults thrown like forks from hand into heart. Billy is stuck in the middle, trying to make sense of the dysfunction. His family love each other “like a straight jacket.”

ACT’s Tribes, by English playwright Nina Raine, follows the story of Billy, an oral deaf man born to a chaotic and dysfunctional hearing family. They struggle to communicate and listen to him thoughtfully and intently, in denial of his deafness and taking no interest in learning American Sign Language. An oral deaf person who himself never learned ASL, Billy encounters Deaf culture for the first time through a new love, Sylvia. He delves into ASL, communicating to and confronting his family members on the ways they have failed him. Tribes interlaces narratives of the hearing and Deaf communities, questioning the meaning of belonging.

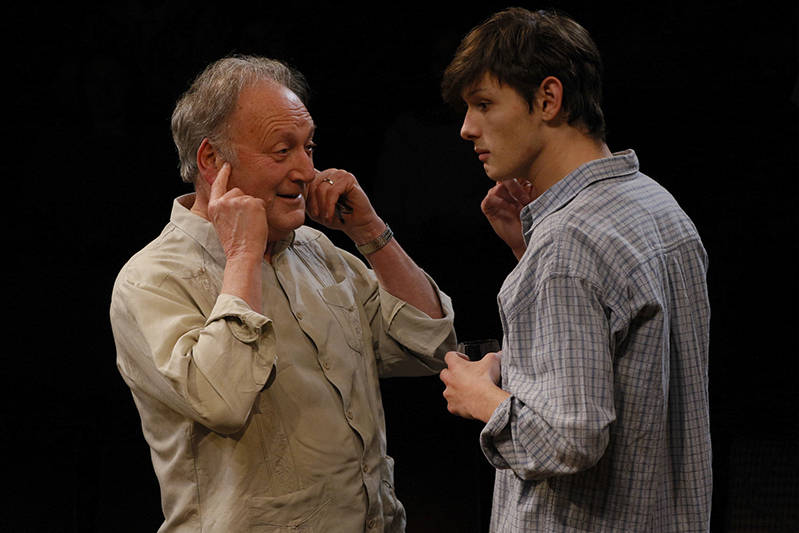

Each child in the family is at a crossroads. Dan, Billy’s brother, is directionless and ungrounded, easily influenced by the discouragement of his father, Christopher. Plagued by voices in his head, Dan’s mental and physical state deteriorates throughout the show, which the audience can track through the accumulation of grime on his clothing, a testament to Rose Pederson’s attentive costume design. Adam Standley’s portrayal of Dan’s complex duality—an academic writing a thesis on the limitations of language while battling depression, struggling to find language that feels like his own—is poignant. “Language is radically indeterminate,” Dan says. “How do you convey a nexus of feeling with words?” This theme, the limitations of spoken language as opposed to sign, is explored throughout the play.

Everything in Billy’s life changes when Sylvia collides with him outside a restroom at a college party. The lighting is dim, and the deep bass of dance music is present in the background. Their chemistry is automatic. In their first few minutes together, Sylvia signs to Billy, drunkenly informing him of the drama she’s dealing with on the dance floor. As she does, her words are projected onto a piece of molding hanging from the ceiling. Billy gazes at her with a half-smile, not understanding anything, having been brought up lip-reading. He comes to learn that Sylvia is a child of deaf parents and is slowly losing her hearing; she introduces him to ASL and the Deaf community. “When I met her—something just clicked in my head,” Billy later tells Dan. From this point, he’s submersed in the Deaf community, finding solidarity and support.

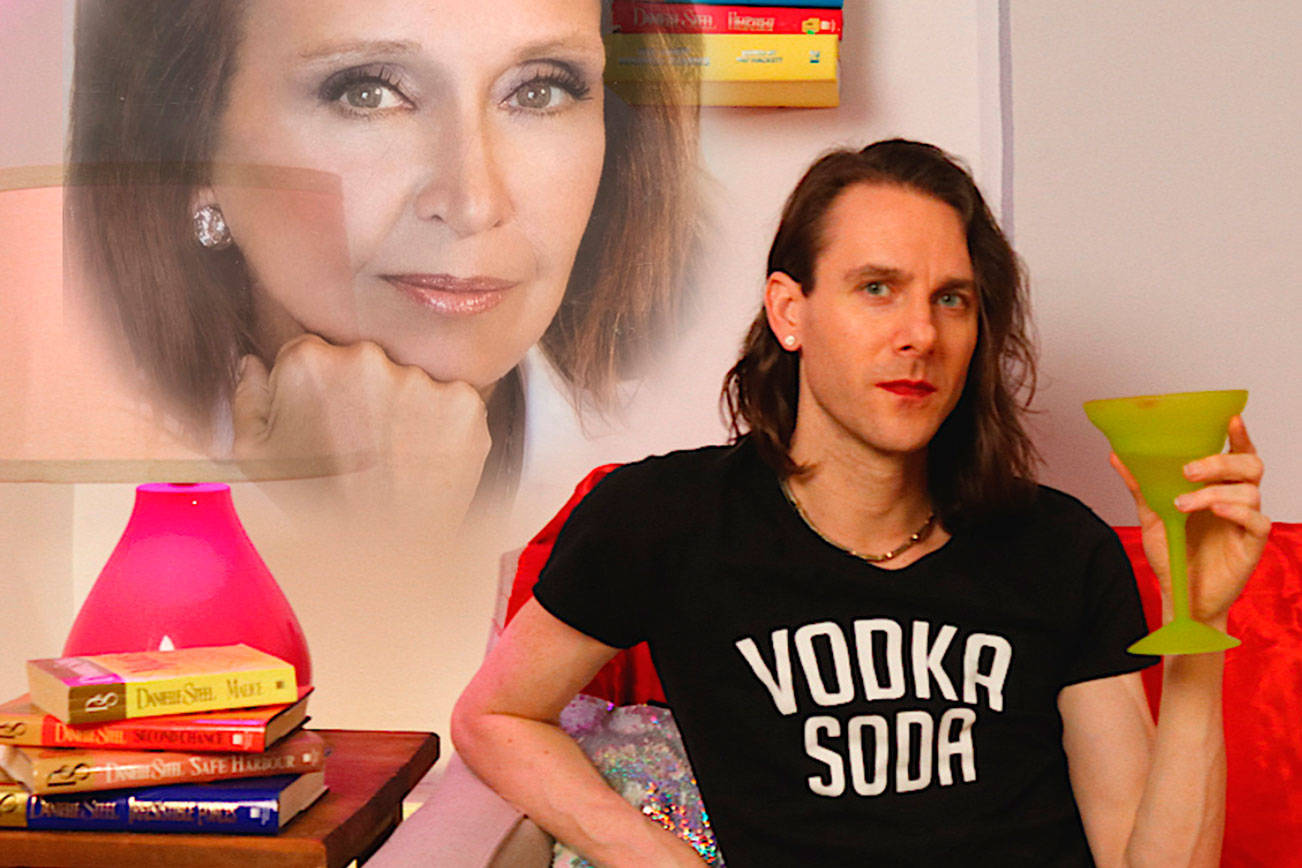

The strength of ACT’s varied communication platforms is central to the success of Tribes. The work of sign master Ryan Schlecht, in combination with the newly implemented Figaro system (a personal closed-captioning device any audience member can obtain) and the translation of ASL to text via projections, all interweave to support the play’s transmission to both Deaf and hearing communities. Schlecht worked with the interpreters and actors for the ASL-interpreted shows, confirming the accuracy and clarity of their translations from spoken English. The production’s accessibility is creative and artful, genuinely supporting both director John Langs’ goals and the play’s themes: to bring the two communities together.

Lindsay W. Evans and Joshua M. Castille, as Sylvia and Billy, uphold the play’s dramatic rhythm and pacing. It’s a rare opportunity for hearing audiences to witness acting through signing. In Tribes’ final scene, Dan struggles to communicate in speech his love for Billy; the only way he can is to sign. As they embrace, their arms cross upon each other’s backs in the sign for love—a moment that reverberates to the core of familial love in a way that saying “I love you” cannot. Tribes, ACT, 700 Union St., acttheatre.org. $15–$68. All ages. Ends March 26. stage@seattleweekly.com