As anyone familiar with deaf culture knows, talking about sign language as a monolith makes about as much sense as talking about spoken language as if English and French were indistinguishable. Generally speaking, if you want to learn English, you need to be immersed in English, not French.

And if you want to learn the sign language called Signing Exact English? According to a petition submitted last week to Superintendent of Public Instruction Randy Dorn, you should be immersed in SEE, not any old sign language.

The petition was signed by 200 parents, teachers, and interpreters, according to Denise Templeman, a Seattle parent who spearheaded the effort. Templeman, whose deaf son Nathan is now 12, was galvanized by her experience with Seattle Public Schools. When she moved to Seattle about six years ago from California, Nathan had almost no language, spoken or sign. He had a cochlear implant, a device that can allow deaf people to process spoken language by sending signals to the brain. But it wasn’t working properly. And the problem had held up his learning of sign language too.

Templeman soon found a haven for Nathan at the Northwest School for Hearing-Impaired Children, a private school that focuses on SEE, a language that closely follows the grammar and vocabulary of English. In contrast, the more widely known American Sign Language uses a different word order, and sometimes expresses what would be a phrase in English with just one sign.

Fans of SEE believe the similarity to English better prepares deaf children to function in the aural world, and makes it easier for them to read and write. Templeman adds that SEE is also useful for people with cochlear implants, because the signs match the aural signals.

For Nathan, it worked. At his private school, he became a prolific reader and writer. “We knew there was a smart kid in there,” Templeman says. But Templeman thought there should be a public-school option for her son too. When she inquired with the Seattle district, she says it offered Nathan a placement in its deaf program at TOPS, a K–8 school on Capitol Hill. She says she visited the classroom, but found a “chaotic” program. Teachers were signing only key words, and in ASL, not in SEE.

She is not the first person to complain about the program. A Seattle Weekly feature story last year (“Deaf Jam,” March 9, 2011) focused on the plight of a deaf boy named Tino Udall, who has cochlear implants. Udall’s parents wanted an education for their son that helped him use the implants to learn spoken language, and found the TOPS program unable or unwilling to do so. The district argued it was offering spoken language in the classroom. As for Templeman’s lament, spokesperson Teresa Wippel says she needs more time to investigate before commenting.

Templeman battled with the district over whether it is required to teach in SEE, taking the matter all the way up to the U.S. District Court. Judge James Robart agreed with the district that it did not have to, saying that under state law, public schools can teach deaf students in any sign language, and need not be limited to an “individual’s particular sign code.”

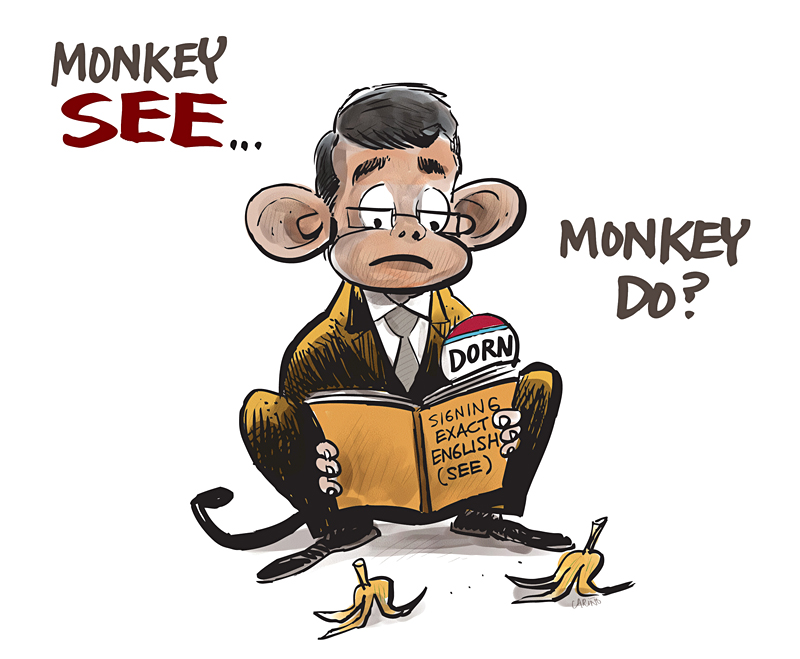

So now Templeman and her supporters are taking the matter up with State Superintendent Dorn. Noting that Templeman’s case is not isolated—that throughout the state “children who have a hearing loss are held back educationally because public-schools personnel do not provide a communication system that provides full access to the English language both visually and auditorily”—the petition asks Dorn to establish a regulation that would require districts to teach SEE to children who use the language at home.

Dorn has 60 days to respond.