The time is long past when a museum had to be embarrassed about hosting a Norman Rockwell exhibit. He’s been respectable since at least 1999, when he received a benediction from New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl, who wrote, “Rockwell is terrific. It’s become too tedious to pretend he isn’t.” This isn’t put-on populism. Organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum, TAM’s visiting show American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell makes clear just how terrific he really is. In our own exhausted age of cultural recycling, riffing, and appropriation, Rockwell stands taller than ever.

Rockwell (1894–1978) is overfamiliar, but that’s only because he was so astonishingly good at what he did. As Eminem once observed of his own skills, “You ain’t even impressed no more, you’re used to it, flows too wet, nobody close to it, nobody says it, but still everybody knows the shit.” This show is full of shit you know: the grandma serving turkey, the boys fleeing past the “No Swimming” sign, the little girl staring in the mirror, etc. Some of it is cloying, but none of it is stale. The joy of Rockwell—magnified in the 44 original oil paintings on display—is in the absolute clarity of his vision. When a man rises to speak at a town meeting in Freedom of Speech, we can practically hear his endearingly awkward, folksy words. They’re clear from his honest face, his workingman’s hands, and the expression of an older man who listens with a twinkly-eyed mixture of respect and amused affection. There’s nothing of what we’re told great art is supposed to be about: no mystery, no shock of the new, nothing subversive, nothing of the sublime. The only awe is in the draftsmanship and the storytelling skill at work. The image is a complete Capra movie in itself.

Sure, Rockwell is sentimental, but so were Frank Capra, Charlie Chaplin, Charles Schulz, and Charles Dickens. And, like Dickens, Rockwell created cartoonishly obvious characters that are redeemed by being so full of life. It’s this savor of reality—just look how perfectly, hilariously recognizable the face of the yawning girl is in Day in the Life of a Little Girl—that makes him more than just the greatest illustrator from an age of great illustration.

Not that Rockwell haters don’t have a point. Who can look at that grandma serving the Thanksgiving turkey to her insufferably happy family (Freedom From Want) and not have at least a passing thought of ax murder? Are we really supposed to feel bemused affection toward a surly hick cop (Welcome to Elmville)? And wouldn’t it be awesome to set off a firecracker in the bedroom where a Ward-and-June couple are tucking in their kids (Freedom From Fear)?

But as Schjeldahl said, most of the time it’s too much work to resist Rockwell. It’s even harder to do so while standing right in front of his immaculate, light-filled canvases. Their surprising size—upward of three-and-a-half feet tall in some cases—makes the perfection of their surfaces even more dazzling. After the main gallery of the paintings themselves, the show continues in a smaller second gallery containing every cover Rockwell did for The Saturday Evening Post between 1916 and 1963. Zooming out from the rich details of the canvases to this expansive view of Rockwell’s career, it becomes clear in a stunning flash just how much sheer labor is represented by the 323 covers.

The show posits as its centerpiece Murder in Mississippi, Rockwell’s 1965 depiction of the murders of three civil-rights workers the prior year. Uncharacteristically dark, and not altogether convincing, it was painted partly as a form of penance for previously not having resisted the Post‘s policy of depicting blacks only as service-industry workers (it was done for Look magazine). Treated as a Very Significant Piece, Murder is displayed with documentation, source materials, and handwritten notes. (“If I just had a bit of Ben Shahn in me, it would have helped,” writes Rockwell of the left-leaning artist and contemporary.)

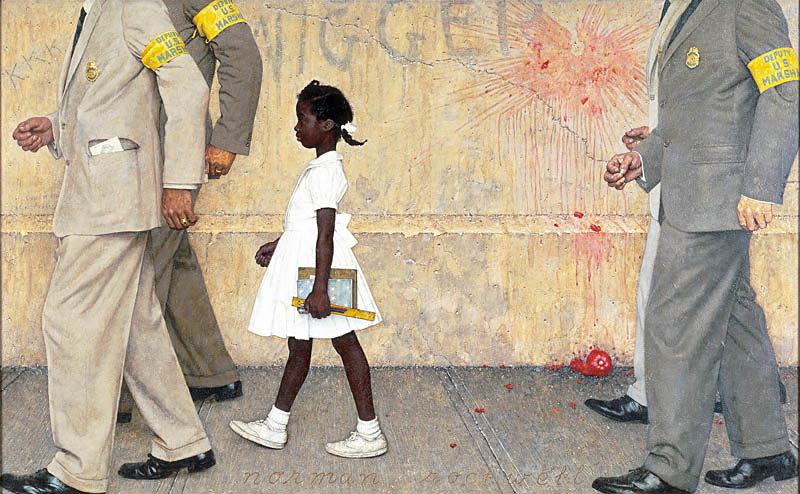

Far more effective is 1963’s The Problem We All Live With, which depicted for Look the first black student to attend a white school in New Orleans. (Its still-living subject, Ruby Bridges, will speak at the UW-Tacoma’s Philip Hall, 2 p.m. Sat., May 21.) Rockwell lavishes his full powers of tenderness on the frail 6-year-old Bridges, dwarfed by the federal marshals who escort her. Unseen is the mob of bigots who’ve thrown a tomato and scrawled an epithet on the wall behind her. This painting—which packs an intense wallop in person—shows that Rockwell’s sentimentality may involve nothing worse than an excess of common decency.