Things are always darkest not before the dawn, but just before they go completely black. At least that’s the gist of Dying City, a psychodrama that doesn’t so much unfold as coil, python-like, around everyone in proximity. Actors and audience alike are pulled closer with each revelation, but the bond is anything but pleasant.

Christopher Shinn’s 2006 potboiler about an Iraq War widow confronted by her late husband’s identical twin is a spelunking expedition into the depths of personal trauma and the measures survivors will take to cauterize their wounds. Kelly (played by SPT artistic director Shana Bestock) is a shell-shocked husk of a woman, given to bleary-eyed hours spent staring at TiVo-ed episodes of Law & Order and The Daily Show. Before her husband’s deployment, she poured herself into her counseling career and her marriage, and now she’s pretty sure she was severely mistaken about both.

When her late husband’s gay twin, Peter (Chris Maslen), shows up at the door, she’s cordial and indulgent as he blathers on about his budding career as a movie actor (he’s about to be “famous,” he confides in a near-whisper) and the hissy fit that sent him storming offstage mid-performance in a local production of Long Day’s Journey Into Night. He’s vain, he’s lost, he misses his brother Craig, and he seeks the solace of the one person he believes misses him just as much. Too bad, then, that Kelly would rather not reminisce, and it turns out that Craig (also played by Maslen in a series of flashbacks) did the worst of his dirty work far from the battlefield.

Bestock plays Kelly with a zombie-like exhaustion. Her eyes are hollow and vacant, her body language distant, and she raises her voice like a woman who never learned how. It’s a shame that when she is required to react to the most devastating plot twist, her energy level doesn’t rise to match. She’s defeated before she has reason to be.

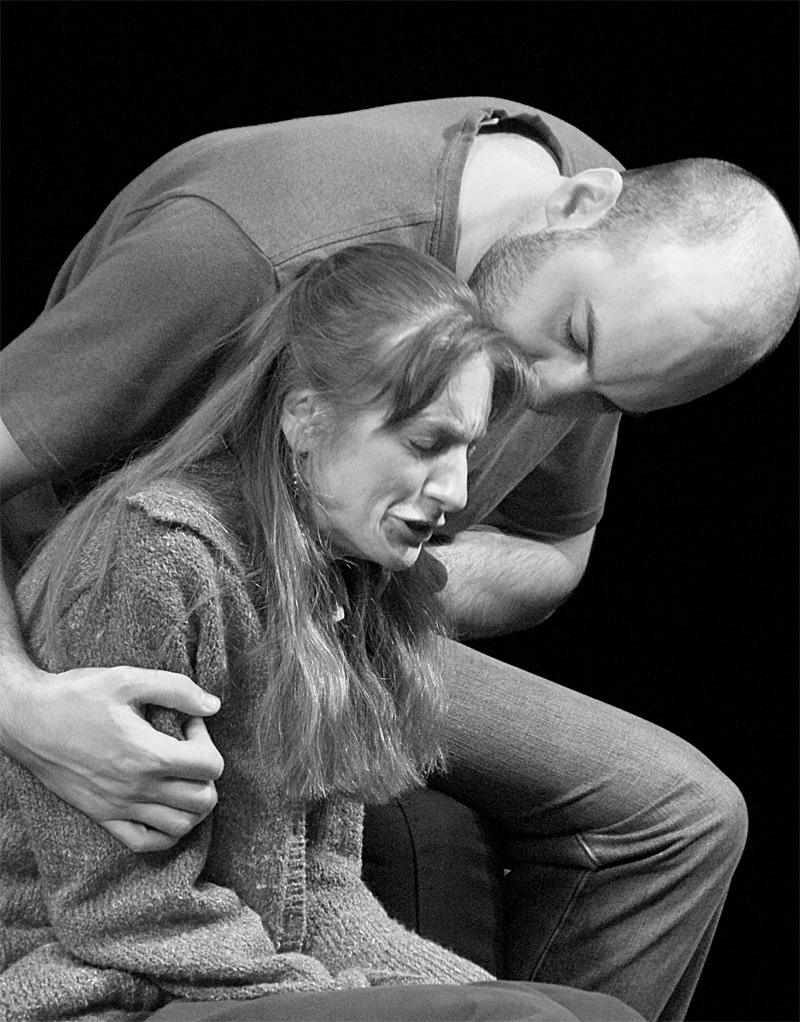

Maslen, on the other hand, is pitch-perfect throughout. As gay Peter, he’s got just enough twinkle and affectation to be believable without slipping into Perez Hilton territory; as Craig, he’s a bundle of repressed urges and self-loathing. There’s surgical precision in director John Vreeke’s staging; he allows nothing to interfere with these characters circling one another in ever-tightening spirals.

In less than 90 minutes, you’ll see much of what the nation has gone through since 9/11. It’s hard to believe that this week marks the beginning of the eighth year America has been at war in Iraq. That’s twice as long as the World War II engagement that Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg are commemorating right now in HBO’s miniseries The Pacific. More than that, the contrast between wars couldn’t be more pronounced. We have no war heroes anymore. People come and go from Iraq almost without notice. Some die, others are maimed, and many carry scars invisible to the naked eye. Outside of a few campaign speeches, there isn’t much talk of service or the sacrifices made by those who go and those left behind. And while countless pieces have been written about the expense of our War on Terror, Shinn argues that we’ve yet to learn the true cost.