The Village Theatre manages to smoothly achieve what so many other performing-arts groups struggle with. Not only do they balance shameless crowd-pleasers (Show Boat, The Importance of Being Earnest, Neil Simon) with novelty, but they nurture new work and make it a selling point. The company’s biggest triumph in this department is Next to Normal (with book and lyrics by former Village associate artistic director Brian Yorkey), which went from Issaquah in 2005 to Broadway, earning 11 Tony nominations and three wins, including Best Score.

A first draft of Chasing Nicolette debuted in Philadelphia in 2004 and ran off-Broadway the next year. It was then fine-tuned at Village Theatre’s annual Festival of New Musicals, where it made a splash last year. It’s now been brought back for a full production. With its brisk sense of fun and ensemble cast of 10 rewarding roles, high-school drama departments, especially, are going to eat this show up.

As source material, book author Peter Kellogg seems to have found perhaps the earliest prototype of the American musical’s favorite boy-meets/loses/wins-girl plot: Aucassin and Nicolette, a medieval troubadour tale about a Christian nobleman and a Muslim slave (who’s really a princess in disguise, of course). Among the other theatrical archetypes here is Valere, the beleaguered, lives-by-his-wits, plot-driving comic servant, traceable from the Greek comedies of Plautus (and updated in the character of Pseudolus in Sondheim’s A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum) through commedia dell’arte (with a stop at Mozart’s Leporello) and up to… well, servant characters have kind of gone out of fashion in pop culture (anyone remember Shirley Booth’s Hazel from ’60s TV?). It’s the sort of role master clowns like Zero Mostel would have played 50 years ago and Nathan Lane 10. As Valere, the excellent Nick DeSantis didn’t make me miss either of them.

The fairy-tale, troubadour flavor is preserved by Kellogg’s decision to author the whole thing in iambic-pentameter rhymed couplets. At first I was impressed by the cast’s ability to keep this lengthy and intricate book zipping along—in sheer number of syllables, it’s surely the equivalent of three Rodgers-and-Hammersteins. But about halfway through Act 1, I realized the nimbleness of the actors’ pacing was enabled by the dialogue’s formal meter: If the words you speak allow you to settle into an easy, regular rhythmic groove, you can whip through pages and pages of them and still keep it all sounding perfectly natural and unhurried. Kellogg’s rhymes, too, now and then approach Sondheim’s, or W.S. Gilbert’s, in cleverness.

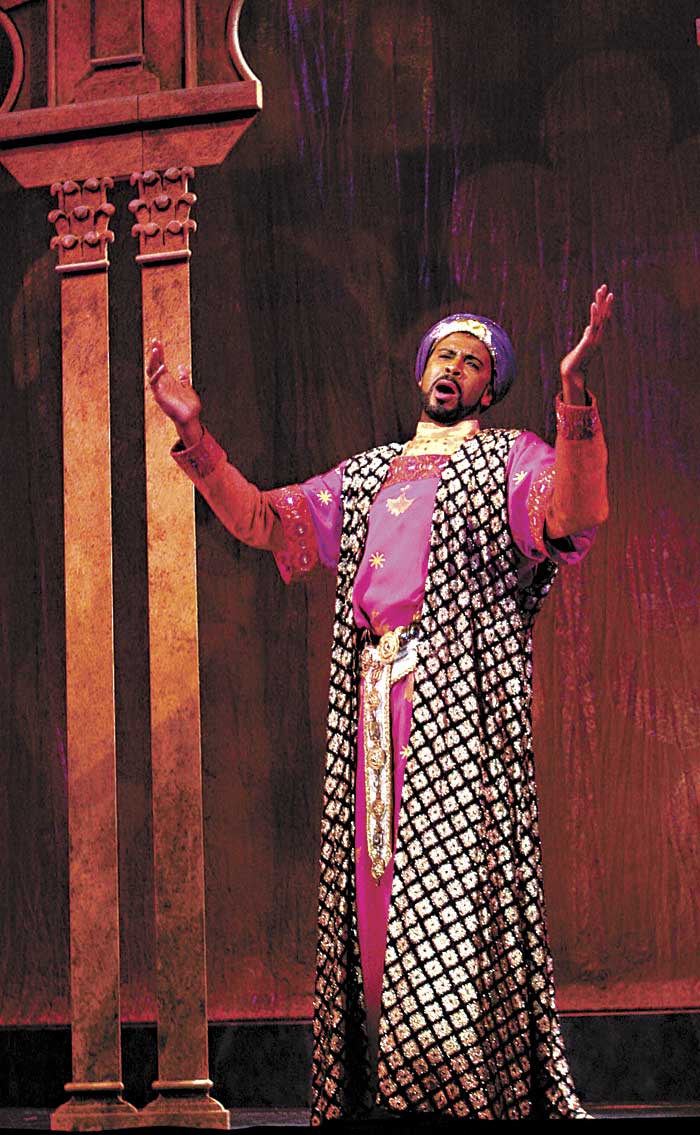

David Friedman’s songs are perky and catchy, mesh comfortably with the lyrics, and offer star turns for the leads—which Tanesha Ross, as Nicolette, takes particular advantage of, with her blooming, acrobatic soprano just on the border of opera, as does Timothy McCuen Piggee, a classic leading-man baritone, as her father the King. (Not that it matters how strong the voices are, given how overmiked this production is. And Village Theatre’s not a large house to begin with.) Welcome touches of medieval color include recorder and lute in the pit (thanks to Bruce Monroe’s orchestrations) and hints of open-fifth drones and Gregorian-chant modality. But these are jewelry, rather than the music’s body, heart, and brain; the songs lack the distinctiveness and personal profile of the words. In every style and no style, the score’s rarely more than functional.

Scott Fyfe’s tripartite revolving set spins us quickly from convent to dungeon and southern France to Carthage. Aside from the opening number, in which the characters bemoan high taxes, religious conflict, and other plus-ça-change tribulations (surprise! It’s 1224, not 2009), the subtext stays subtext. That Kellogg chose not to hit us over the head with the Christian/Muslim thing—which could have brought the show some buzzy, politically relevant cachet, but which no one over age 8 will need to have pointed out to them—seems, paradoxically, like a rather sophisticated decision. We’re adults; we can handle a little fluff.