Considering that opera is an art form based wholly on the suspension of disbelief, it’s odd that it has so little truck with surrealism. It’s only a small step away: Since everyone’s already singing, why not acknowledge the artifice and embrace that otherworldliness for theatrical effect? Ravel made a move in this direction with his 1925 one-act The Enchanted Child—a young boy throws a tantrum, and toys, animals, and other fantastical beings come to life and confront him.

For the Seattle Opera Young Artists’ annual spring presentation, director Peter Kazaras takes this fairy tale one notch further by setting it in that modern-day garden of Fellini-esque grotesques, the New York City subway, even more surreal as set against Ravel’s fragrant, ethereal music. Riding home from school joined by a girl in a squirrel head, the boy (at the performance I attended, an excellent David Korn) meets a gallery of commuters, from a bag lady to an extravagantly Mohawked punk. There’s no plot; each of these characters gets his or her moment, and at the end the chastened boy learns to behave. It’s great fun, genuinely touching and lovely as well as imaginatively trippy.

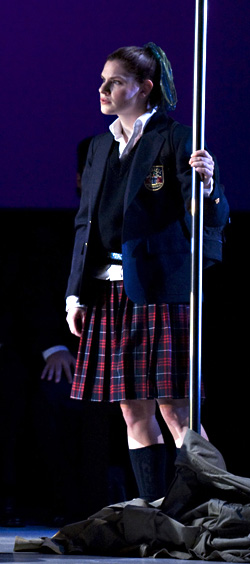

If ever there were a timeless subject for satire, it’d be greed, with hypocrisy not far behind, and so Kazaras’ 700-year updating of Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi, the second half of this double bill, succeeds effortlessly. The rich Buoso Donati dies—during a soccer match to which his Eurotrash relatives are glued—and when they discover he’s left everything to a monastery, they enlist the shrewd title character to forge a new will. As played by Joshua Jeremiah, Schicchi is a Guido in sunglasses and track suit. If the satire were more specific, more recognizable to the audience, it’d be even funnier, but the characters sing constantly about Florence and the Arno; the time can be changed but not the place. (In a clever touch, Gherardino, the youngest Donati, wears the same school blazer and iPod as Ravel’s enfant.)

Puccini gave his young ingenue lovers the only two excerptable arias in this tight-knit ensemble opera. “O mio babbino caro” is the one everybody knows, and the role of Lauretta is quadruple-cast to give as many sopranos as possible a crack at it. The performance I saw was Ani Maldjian’s night, and she skillfully drew from the audience the requisite collective sigh without pulling us out of the story. Marcus Shelton, as her fiancé, Rinuccio, sings his ode to Florence with heroic panache. One mark of the Young Artists productions is an ease and flexibility, both physical and mental, among the cast that looks like it might come from musical-theater experience. It serves them well for both Ravel’s dry wit and weirdness and Puccini’s broader caricatures, and I hope that as their operatic careers progress, it doesn’t get bred out of them.