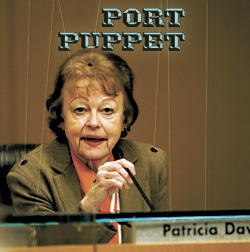

It’s fitting that in squeaky-clean Seattle, the most disreputable elected official is a part-time public servant, former citizen activist, and 72-year-old grandmother.

But don’t underestimate her impact. Working a mere 20 hours a week, and collecting just $16,800 a year in salary and per diem, Port of Seattle Commissioner Pat Davis has managed to amass an unrivaled record of bungling, back-dealing, and questionable behavior.

The job of commissioner, ostensibly, is to be the public’s eyes and ears at the Port, which employs 1,800 people, generates $12 billion in related business regionwide, and this year will collect nearly $80 million in property taxes from King County residents.

But for Davis, closed doors and a rubber stamp appear to have been the preferred tools of the trade. She’s been especially accommodating over the years to former Port CEO Mic Dinsmore, whose policies she regularly supported and for whom she tried to supply a highly generous retirement package. (The plan was abandoned last year when it became public.)

The retirement flap was just one in a series of recent Port scandals, from sexually explicit e-mails traded among Port cops to no-bid contracts handed out at the airport. In the wake of a scathing state audit in January, the Port’s activities under Dinsmore are now being investigated by the U.S. Department of Justice for potential criminal wrongdoing.

Habitually uncontrite, Davis has presided over it all. She also had a hand in Seattle’s biggest black eye, the 1999 World Trade Organization meeting that left the city smoldering. Those who’ve worked with her puzzle over whether she’s conniving or clueless, but Davis has proved to be a cunning politician, building the alliances and securing the backers she’s needed to survive. Indeed, she’s held her job longer than almost any local pol currently in office.

But Davis may finally be getting ready to hang up her rubber stamp. Most Port observers think she won’t bother seeking re-election next year. (Davis declined to speak to the Weekly.)

But that’s not good enough for at least one local activist. Chris Clifford has made it his mission to give Davis the boot, but he first needs permission from the state to get a recall vote on the ballot, and Davis has fought the effort all the way to the state Supreme Court. If Clifford wins, he’ll have six months to collect approximately 150,000 signatures. If he loses, the controversial commissioner will get to depart into the sunset, like a jet lazily lifting off from Sea-Tac’s pricey new third runway.

Long before she got caught stitching outgoing chief executive Dinsmore that golden parachute, Davis was a member of the League of Women Voters and the leader of a citizen group called Port Watch. She was also an outspoken advocate for increasing public scrutiny of the Port, and for protecting Seattle’s shoreline for marine-dependent uses. Davis, the daughter of a Wenatchee apple rancher and a school teacher, who raised her three children in Seattle, was a good fit for what is largely a group of amateur public officials. Married to an associate professor of pediatric dentistry at the University of Washington, she spent decades managing the books for her husband’s part-time private practice while volunteering on the boards of organizations like the Seattle-King County Economic Development Council, the Trade Development Alliance, and the International Women’s Conference.

In 1985, she became the first woman elected to the Port Commission. It wasn’t long before she became commission president, overseeing a quasi-governmental agency that controls Sea-Tac Airport, the giant container facilities along Elliott Bay, and numerous other swaths of the Seattle waterfront.

It also wasn’t long before Davis, the reformer, became something else—a cheerleader for the wishes of Port tenants, real estate developers, and the Port chief executive. At the behest of Dinsmore, she helped pass the policy at the root of the practices that have come under scrutiny by a recent state audit, which found millions of dollars in sloppy Port spending on everything from credit cards to no-bid construction contracts.

Normandy Park resident Helen Kludt, who has long opposed Sea-Tac expansion efforts, and who held a fund-raiser at her home for Davis when the candidate first ran for office, still marvels at the transformation. “She was an entirely different Pat Davis than she is today,” Kludt says. “It seemed like after she got into office, there was a flip-flop. She just went along with the big boys.”

Davis’ days as a yes-woman, and the Port Commission’s abdication of its oversight role, began together with the quiet passage of something called Resolution 3181. The change was pitched in 1994, two years after Dinsmore took control and a time when the Port, in its quest to help Seattle’s waterfront become more “world-class,” was getting more involved in real estate development. The idea was to allow Port staff—about 20 policy analysts and operations personnel—and the chief executive to bypass commission approval for everything from property transactions, capital projects, and lease agreements to work contracts and use of idle Port funds.

The resolution was approved unanimously and without debate by the commission while Davis was its president, according to meeting minutes. It essentially gave Dinsmore free reign to do what he wanted with Port projects, as long as they cost less than $200,000.

“It gave Dinsmore everything,” says Fred Felleman, Northwest consultant for Friends of the Earth, an environmental nonprofit that keeps an eye on port pollution. “The commissioners neutered themselves.”

It was just the first, and biggest, step in a long tenure of accommodation. Even when commission approval was needed, Davis was there for Dinsmore, giving her endorsement for the Port’s massive waterfront development, northwest of Pike Place Market. It includes the Bell Harbor International Conference Center and the Bell Street Pier, which have sucked up large amounts of public money with little return, and World Trade Center West, in which the Washington Council on International Trade (WCIT), a nonprofit group that Davis led from 1994 to 2001, leased prime office space at discounted rates—a deal some say smacked of favoritism.

She voted with the commission to let yachts dock at Fishermen’s Terminal, and continues to be a vocal advocate for the Odyssey Maritime Discovery Center housed at Bell Harbor that’s drained nearly $5 million in public funds since it opened in 1998. She has also pushed for a big mixed-used development on a piece of Port property just north of downtown in an area called Interbay, a plan that has angered the City Council and others who want to preserve Seattle’s dwindling industrial-zoned lands.

“We think it should be a combination of manufacturing, industrial, and some office, but not a biotech center,” says John Kane, chair of the Ballard Interbay Northend Manufacturing and Industrial Center action committee. Kane, who ran for the Port Commission in 2005 (though not against Davis), objects to the Port agenda that she has supported. “They’re not real estate developers,” he argues. “It’s a seaport and an airport, and that’s what they should be doing. Let the market take care of the other stuff.”

Davis even supported the Port’s most extreme development idea: a proposal by Nitze-Stagen to turn the giant container yard at Terminal 46, in the shadow of the stadiums, into an urban village. She backtracked on the issue after pressure from the longshoremen’s union.

Explaining Davis’ initial support for the plan, Jack Block Jr., an ex–commission candidate and former executive board member of the longshoremen’s union, says the chief executive liked the idea. “She was close to Dinsmore and lost sight of what the Port was meant to do,” he says.

Kane’s impression of Davis is that she sees the Port Commission as more of a board of directors that’s following the lead of a CEO. “The day-to-day decisions, I think from her point of view she would say that’s what the CEO is there for, and the commissioners are there to approve budgets and to make sure things are going the right way. I think Pat’s a supporter for what the CEO wanted.”

Preservationist and executive director of the Kalakala Foundation Art Skolnik says Davis’ affinity for the former chief executive was hard to miss. “She doesn’t have an opinion other than Mic Dinsmore’s opinion. If he wanted something, she’d be there to give him the vote,” says Skolnik, who fought for years—unsuccessfully—to moor the historic ferry Kalakala on the pier that houses the Odyssey museum. “[Dinsmore’s] technique was to treat commissioners like little diamonds and pearls. They wouldn’t want to go sideways on him so that he would take it away.”

Dave Gering, executive director of the Manufacturing and Industrial Council, who’s long disagreed with Davis on the proposed Interbay development, describes Davis as “a good human being” who went “way too far in following the lead of the Port’s staff and the Port’s consultants.

“It’s disappointing because I do think highly of her,” he says. “I’m not questioning her integrity. I’m not questioning her intellect, but she’s had a thread of errors in judgment.”

At a February Port Commission hearing, Davis sat cross-armed, her lips pursed, as new commissioner Bill Bryant discussed the commission’s post-audit move of putting a moratorium on large construction projects until contracting reforms are in place.

“I think we all agree we need to establish a new culture at the Port,” he proclaimed, prompting Davis, dressed in a turquoise blouse and black jacket and wearing gold-rimmed glasses and a moon-shaped brooch, to demand the floor.

“We need to make clear that we’re not going to bring this place to a halt. There will be a terminus to this [moratorium]. I’m not sure what you have in mind,” Davis said, shooting Bryant a defiant look. “Just so long as it’s not reported that the Port has shut down.”

Commissioners agreed to lift the moratorium about a week later with the caveat that it could be reinstated at any time. The panel plans to revisit the Port’s progress in shoring up its business practices in June. However, despite the ongoing federal investigation—and being in the uncomfortable situation of having to undo policies that she’s the only one still around to answer for—Davis acts as if it’s business as usual. Her tone during the meeting is of someone who wants to make sure this tiresome business of reforms and audits is wrapped up in short order, preferably before the beginning of the construction season.

Those who have observed Davis for years say patience has never been one of her virtues, particularly when it comes to newly minted commissioners trying to change the status quo.

One memorable example occurred in early 2006 during one of the first meetings attended by freshly elected commissioner John Creighton. Commissioners were asked to approve leases related to a $130 million plan to swap the cruise ships downtown for containerships, moving the pleasure boats to a terminal in Magnolia. The new cargo terminal was slated to be operated by longtime Port tenant Stevedoring Services of America, or SSA Marine. The deal included a 30-year lease with SSA for the new cargo terminal and extensions of leases the Seattle-based firm has at two other Port docks. SSA leases the terminals so it can manage container operations for the companies that ship the goods. The leases, the size of phone books, had been delivered to the commissioners just a few days prior to the meeting. Creighton, a corporate lawyer, requested something radical—time to read what he was asked to approve.

Felleman, of Friends of the Earth, was in the audience. He says what happened next was classic Davis. “I’ll never forget; Pat got up there and said, ‘We’ve got a client on the hook [referring to SSA]. We need to close this deal today,'” Felleman says. “Pat was adamant. She was basically saying, ‘Don’t look too closely. We’ve got this deal done.'”

Creighton confirms Felleman’s memory of the meeting. He calls it a “classic example” of what happens when there’s resistance to rubber-stamping. “The attitude I was confronted with was, ‘That’s nice, John, we understand there’s a large learning curve, but you don’t want to be the commissioner that sees Cosco [Chinese Overseas Shipping Company] leave to Tacoma.'” Creighton says. “But I also didn’t want to be the commissioner who approves a $130 million lease that we shouldn’t confirm.”

The commission, under the thumb of Davis, ended up approving the design work for the terminal swap that day and passed the remaining pieces of the leases a few months later. The project, however, despite Davis’ urging that commissioners shouldn’t delay, is about a year behind schedule.

Davis’ extracurricular activities have been, if anything, more troublesome. It was as leader of the advocacy group the Washington Council on International Trade that she made one of the most fatefully bad decisions in the history of Seattle: inviting the WTO to hold a 1999 conference in our fair city.

In a December 1998 letter, Davis promised the controversial group that “our corporate community” and “Seattle’s community [stand] ready” to host the event. She was wrong on both counts.

She was undeterred, even by stories of the riots that followed the organization’s visit to Geneva in May 1998, which Davis famously told the local press “just didn’t register” as she was extending the welcome mat for Seattle and surmising that security would only run in the neighborhood of $1.5 million.

Less than a year later, the WTO answered Davis’ invite and an underprepared Seattle was left smoldering, shattered, tear-gassed, embarrassed—and holding a $9.3 million bill.

The city’s WTO Accountability Review Committee later called the process of inviting the event to Seattle “haphazard and careless” and admonished Davis for giving three versions of who she said would pay for the event. According to the report, Davis said initially that “major corporations” would chip in and next promised that the city would pick up the tab. Finally, contrary to her earlier statements and her letter to the WTO, Davis told the panel that she believed the federal government would pay the balance of the security costs.

The review committee concluded that no city officials were shown the invitation or knew about the bid before Seattle was chosen to host the WTO—a decision made about a month after Davis sent her letter. The report noted that the letter had no “cc” on its face and that Davis “did not even follow basic business procedure” in failing to send copies of the bid to the affected governments.

Ultimately the panel recommended sanctions against Davis that included written censure, or at the very least the promise that the city would “not do business with Pat Davis or the WCIT for a period of time.” Other public officials were, of course, held culpable for the WTO fiasco. Mayor Paul Schell and Chief of Police Norm Stamper both paid with their jobs. But Davis quietly went back to her jobs as both Port commissioner and head of the council.

Davis’ close relationship with Dinsmore, and his ties to the deep pockets of campaign donors, has helped sustain her 23-year political career.

She was most recently re-elected in 2005, when one of her largest donors was Citizens for a Healthy Economy, a PAC made up of Port tenants, developers, and business owners, which gave $10,000 directly to her campaign and spent another $90,000 on things like polling and mailers, with Davis as the primary beneficiary.

Seattle Weekly‘s George Howland Jr. reported in May 2006 that the group had been advised by Dinsmore to contribute money to Davis. One e-mail, obtained through a public records request, referred to a plan to conduct polling on her behalf. Though Dinsmore confirmed talking about a poll with PAC organizer (and real estate developer) Robert Wallace, he denied campaigning for Davis.

The e-mail from Wallace to Dinsmore also talked about the upcoming election: “As [Nitze-Stagen principal Frank] Stagen and I were discussing today, our friendship with you is costing us a lot of time, money and political capital. But we’re all on the side of angels, and this is pretty important stuff. I’m actually feeling optimistic about our chances in November.”

To which Dinsmore replied: “You are such a great………… You will be repaid in another life…………. Have a wonderful week and THANKS!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!”

Fletch Waller, who worked on the campaign of Davis’ opponent that year, former Microsoft executive Jack Jolley, remembers being floored by Dinsmore’s bravado. “It’s a major question when the CEO is campaigning on behalf of one of the members of his board of directors to which he’s accountable.” Jolley managed to raise almost $200,000, but got only 47 percent of the vote.

One of the contributors to the PAC was John Oppenheimer, a longtime friend of Dinsmore and president and CEO of Columbia Hospitality, which has a multimillion dollar contract with the Port to operate the Bell Harbor conference center and the World Trade Center. “I’m supportive of anyone who wants to volunteer their time for public service,” he says, explaining his support for Davis.

Under Davis’ watch, Columbia Hospitality was awarded these contracts without competition, and operation of the publicly owned waterfront facility has, until recently, gone without financial audit or management scrutiny.

Oppenheimer, a short, jovial man known for his big personality, was at a February Port Commission hearing testifying against a proposal to terminate the Port’s agreement with his firm for operating the Odyssey. The commission ultimately voted to end Columbia Hospitality’s involvement by year-end and put out a request for proposals for a new tenant/operator for the space. Even until the final vote, however, Davis was agitating on behalf of Oppenheimer’s firm, arguing that if there must be an RFP, it should go out as soon as possible to help Columbia Hospitality better plan for future booking at the rest of the conference center.

Dinsmore, Davis, and Oppenheimer were aligned not only on Port business, but also on vacation. They all own summer homes on the banks of Lake Chelan in Central Washington. According to property tax records, Davis purchased hers first in 1996, followed by Dinsmore in 2002 and Oppenheimer in 2004. Asked about his relationship with Davis, whether they socialize at Chelan, Oppenheimer offered: “not very much. I know she has a home there.”

Another contributor to Davis’ 2005 campaign, Kinzer Real Estate Services, secured a $550,000 consulting contract for the Port’s proposed Interbay development a month after donating $5,000 to the Citizens for a Healthy Economy PAC in May 2005. Kinzer Real Estate also gave $500 directly to Davis seven days after the contract was inked and another $500 to the commissioner in both November and December of 2005.

Davis has also been a loyal caterer to the needs of SSA, which gave her more than $10,000 in 2005 and gave the PAC another $10,000. In addition to the lease change Davis helped muscle through, she voted in favor of a $10 million bridge between SSA’s terminals 25 and 30 in October 2005 after collecting thousands in donations from the company—something that seemed unseemly to former commissioner Alec Fisken, who lost his seat to Bryant last year.

“There was no change in the lease at all,” Fisken says. “I complained. I said, this seems like a pretty fancy favor.”

But Kane, the former commission candidate, cautions against the assumption of a quid pro quo.

“I don’t think Pat’s like that,” he says. “When I ran for Port commissioner, a lot of different kinds of people gave me money.”

The Dinsmore retirement brouhaha began with a 2006 memo, signed only by Davis, that promised the former chief executive his $339,841 salary and benefits for up to a year following his departure from the Port. Davis offered the severance under a policy designed to compensate Port employees whose jobs were being eliminated (not to pad the retirements of high-ranking officials). Nonetheless, the memo said the benefits were to assist Dinsmore in his “transition away from the organization.”

When news of the deal surfaced last spring, the other commissioners were outraged. They said they knew nothing about the planned payout and chastised Davis for acting unilaterally and without a public vote. Commissioners Creighton and Lloyd Hara privately called for her resignation.

While the Port’s ethics board later found there had been no official wrongdoing, it was largely because there’s no provision in the ethics code to cover Davis’ actions. Dinsmore opted not to seek the payment the day before the commission ultimately voted against giving it to him.

Enter Clifford, citizen activist and high-school teacher, who began his quest to recall Davis a few weeks later. He’s got to prove wrongdoing to get a vote on the ballot and has already won the blessing of the King County Superior Court. Davis and her attorney, K&L Gates’ Suzanne Thomas, have appealed to the state Supreme Court. Clifford has asked the court for an expedited review of the case and hopes to see a ruling this month.

Davis maintains that she didn’t do anything wrong and argues that she and her fellow commissioners discussed the payout during a closed-door executive session. In her declaration to Superior Court, Davis says she has “nothing to hide,” and “fully supports” sunshine in government. She also takes a swing at the other Port commissioners, saying, “Unlike some of my colleagues who at least initially denied that there had ever been any form of meeting in which these issues were discussed, I have been accurate and consistent in addressing the controversy that has arisen,” according to court documents.

She told KING-5’s Robert Mak in April 2007 that it’s “common in companies, other places” for people to be “let go with a year’s salary.” She again emphatically denied acting alone. “I wouldn’t do anything unilaterally,” Davis says. “I’ve been here for 20 years. Honesty and integrity have guided me. I’d never do anything illegal.”

Meanwhile, the Justice Department continues its criminal investigation of the Port following the state audit that found Port staff got too cozy with contractors, violated competitive-bidding laws, and wasted nearly $100 million of taxpayer dollars during Dinsmore’s tenure. The audit, released late last year, charges the commission with complacency, saying that it provided “insufficient oversight over contracting practices,” and recommends the commission “reassert its responsibility for Port management…and take back much of the decision making responsibility that has been delegated.”

Clifford says his recall effort is as much about kicking Davis off the commission as it is a pre-emptive strike on her legacy.

“She’s hoping for the Pat Davis Pier,” he says. “But when your name gets put up and there’s a whole lot of signatures collected for your recall, there’s not going to be a whole lot of statues that go up in your honor.”

Indeed the Port has a tradition of naming things to honor former commission members. There’s a park in West Seattle named after Jack Block, who at 28 years was the panel’s longest-serving member; a pier at Shilshole Bay Marina named after the late Henry Kotkins; and a fountain and children’s pool at Bell Street Pier named for Paige Miller.

She may not get the “Pat Davis Pier,” but the 23-year commissioner, like it or not, will have left a legacy of another sort: audio taping of all Port executive sessions, and efforts by state legislators to mandate audio taping at municipalities statewide— insurance to guard against future closed-door shenanigans like the Dinsmore parachute.

Davis’ tenure has also spawned a whole new crop of so-called reformers, eager to put their stamp on a new era of improved Port accountability.

Port commissioner Gael Tarleton, for one, is leading the review of Resolution 3181. “It created a culture where the staff was accountable to the CEO and not to the commission,” she says. “Changing the language is one step in the process. Changing the culture is going to take a little more time.”

Tarleton won’t talk specifics about Davis, saying only that she’d rather “leave it up to the voters to decide her culpability.”

Early supporter Kludt, for one, thinks Davis isn’t conniving. “I had a feeling that she was being pressured by other people and just [rolled] over,” she says. “I think she basically probably was a nice person, but I don’t think she was a person who knew how to stand up on her own.”

Former commissioner Fisken says that he still can’t tell “whether she’s naive or scheming” even after four years of sparring with Davis. “She’s a mystery.”