I’ve just left One-Eyed Jacks, the Crocodile-size music venue in New Orleans’ French Quarter, when I stumble upon a quintet of scruffy street musicians who are ambling through a horn-driven, carnivalesque dirge that would not sound out of place on a Neutral Milk Hotel record. I’m particularly struck by the saw player, a waifish young woman taking furtive sips from a canned beer and dragging her bow across the rustic instrument. “She’s one of the best saw players in town,” says her affable, crusty, punk bandmate, nodding his head in admiration as she conjures wisps of ghostly sounds. “Ha!” she laughs dryly. “That’s just because I’m one of the only ones left!”

As evidenced by the saw player’s black humor and the palpable sense of sadness that lingers almost everywhere, this city is still making the painful adjustment to life since Katrina brutally altered its social, political, and physical geography. However, over the course of a 36-hour stop in the city last weekend, I encountered plenty of hopeful signs as well, thanks to journalist Alison Fensterstock and promoter Lefty Parker, two of the most generous, frank, and passionate ambassadors a local underground music scene could ask for. The couple offered me a whirlwind tour of the bars and clubs that have survived to support their community—and helped me understand how NOLA musicians could rebuild the environment that has fostered so much historically significant art.

Fensterstock is the music columnist for New Orleans’ alt-weekly, the Gambit Weekly, and has lived in the area for 10 years. She evacuated to Alabama the day before the storm hit, thinking she would be able to return in a few days, but ended up shut out for months. Parker stayed around much longer, determined to defend and protect the Circle Bar, a tiny punk club where he had booked bands like ? and the Mysterians, the Hold Steady, and even Seattle’s own Spits for years. Because it was located mere blocks from the postapocalyptic spectacle at the Superdome, the physical dangers grew increasingly troublesome. “It wasn’t until I realized that I would most likely be shot on the street soon that I decided it was time to go,” says Parker as he navigates his car through side streets lined with boarded-up businesses as we drive toward the club. When Parker did return to the Circle Bar last fall, he booked what he says was the city’s first post-Katrina club show, a record-release party in October for his band the Interlopers, with bills featuring Quintron and Miss Pussycat, the Oblivians, and Alex Chilton coming together shortly thereafter.

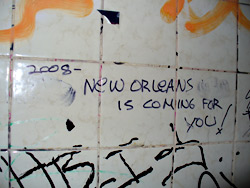

When we arrive, the cozy space exudes all the comforting touchstones of any good punk dive, including a liberally graffitied bathroom and nearly flammable cocktails. While the sizable crowd dances drunkenly to the DJ’s Saturday night soundtrack of the Sonics, Undertones, and Black Sabbath, Parker and Fensterstock fill me in on some of the more disheartening and occasionally surprising side effects of Katrina on their scene. She sees a potential blow to future generations in the shrinking ranks of local high-school marching bands. “Marching bands are the training grounds for so many local musicians,” she explains. “And there just aren’t enough kids here anymore.” On the upside, Parker notes how shifting attitudes and a fresh sense of creative flexibility can create new growth. “There are a lot of supergroups forming, actually,” says Parker. So many musicians that you would never imagine working together are playing in new bands now because they lost half their bandmates. People are a lot more relaxed about lineup configurations from show to show, which keeps things pretty interesting.” He also sees a deepening natural camaraderie between the older roots-rock scene and budding young punks, cross-generational pairings that he deliberately tries to bring to some of the club’s more diverse bills.

And of course, there’s the stubborn tenacity of the punk-rock spirit. When we stop for a nightcap at the Saint, a hedonistic lounge co-owned by former White Zombie bassist Sean “Shana” Yseult, Fensterstock points out that even though there are countless literal and metaphorical roadblocks to rebuilding NOLA, she has unwavering faith in the ability of people to soldier on, even when they’ve undergone spirit-crushing defeat. “There was an initial sense of ‘charging the mountain’ immediately afterwards, and some people got tired and eventually gave up, which is understandable. But the people that are here now are really even more committed than ever.”