When you find yourself getting emotional over a footstool with a bandaged leg that’s meant to represent a crippled boy, you may correctly suspect that you are watching a chamber theater production. Smaller casts, distilled scripts, and simpler sets are the trademark, as are lower budgets. But low budgets don’t necessarily mean lesser quality. Some theater companies are actually choosing to do leaner productions as much for the artistic challenges (and rewards) as for financial considerations. After all, if they can get you to weep over a wooden Tiny Tim, you know the play you are experiencing has accomplished something unique.

At the moment, a number of pared-down productions are filling Seattle’s stages: Seattle Shakespeare Company, which presented a pocket Othello last season, is launching into a Chamber Richard III for January 2006. Book-It Repertory Theatre abridged Cervantes’ sprawling Don Quixote to 10 actors for a fall run, and Strawberry Theatre Workshop is currently retelling Dickens’ A Christmas Carol with just three actors (and the aforementioned stool) in Greg Carter’s adaptation, Fellow Passengers.

So what’s up? Is Seattle theater suffering a budget crunch that’s making companies trim their casts and sets and offer Equity status to furniture?

Myra Platt, co-artistic director of Book-It, which has been adapting novels the stage for nearly 20 years, thinks the chamber format itself is a recurring trend. Yet, she says, “I definitely see a trend of theaters needing to find shows with smaller casts. Usually it’s artistically motivated, and the reward is obviously financial.” After all, she adds, theater “is still a business, and you have to make certain business choices.”

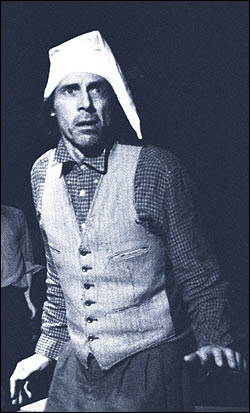

Actor Todd Jefferson Moore agrees. “Theater is really hurting now financially. Chamber productions keep the costs way down. Actors’ salaries are by and large the largest part of the budget.” Yet, Moore also believes that there’s much to be gained from such productions artistically. He should know—he is currently performing in Fellow Passengers, and rehearsing for the title role of Chamber Richard III. This style of theater, says Moore, “is leaner and more interesting, more engaged than these big Shakespeare productions.” And Moore enjoys the challenges of shows that keep the actors onstage often nonstop. “I’m one of those actors who likes to stay busy, rather than hanging out backstage smoking a cigarette.”

When he took on Seattle Shakespeare’s Chamber Richard, director Gregg Loughridge asked artistic director Stephanie Shine, “What does this mean? Are we doing it with four music stands in a bar in New Jersey?” But Loughridge soon developed his own understanding of chamber. “To me, it means scaled down. We’re doing a 14- or 15-person play—maybe more—with only seven people. We’re doing it with a limited set and an audiovisual component, so some characters are virtual.”

Because the story has been transported to a contemporary corporate setting, Loughridge uses office technology to cover for casting limitations—e-mail, video, and PowerPoint productions convey plot points and even some characters. “Necessity is the mother of invention, and out of it comes wonderful things.”

While he acknowledges that it’s “fun to be overwhelmed by a beautiful set and production,” Loughridge finds the smaller show interesting: “In some ways, it’s very liberating. It boils things down to essentials.

“The audience has to forgive you for things that are missing,” adds Loughridge, whose show creatively conveys a “missing” battle scene, a king, and a couple of murdered children. “But the story is still a good one.”

Currently, at least four different versions of A Christmas Carol are onstage in town. Greg Carter, Strawberry Theatre’s artistic director, knows that “ACT is doing [a show] before 400 people a night, paying $40 a ticket, about eight times a week. We need to give the audience something else. We owe them the unexpected.”

Strawberry Theatre uses various clever devices and a wonderfully odd array of props in its attic set to captivate its audience. It also has a wonderful cast. And that’s another important facet: To pull off these demanding shows, you need talented and versatile actors. The company had originally budgeted the show for 11 performers. When it decided to tell the tale with just three voices, it was able to afford three experienced character actors—Marty Mukhalian, Nathan Smith, and an Equity actor in Moore—without adjusting its budget.

Telling a story with a stage full of actors and elaborate props also has its disadvantages, says Carter. “I think it’s too easy. You don’t have to keep track of anything.” A play with just a few characters playing multiple roles and fewer props “forces the audience to imagine what they’re looking at, just as you would in a book. It will keep you more involved if you have to fill in the gaps.”