How come the Great Seattle Writer is an Englishman? And how did he turn his snug aerie on North Queen Anne Hill into a bully pulpit to preach the gospel of good sense and good taste to the nations, via the most respected publications in New York and London (plus Seattle Weekly and Playboy) and a string of best-selling, award-winning, uncategorizable books that mix fiction, memoir, lit crit, political polemics, history, Northwest art history, anthropology, and travel writing into a chimera-style quite his own?

And how is it that the most recent book by this “regional” writer— My Holy War: Dispatches From the Home Front (New York Review Books, $21.95), which he’ll read from this week at Town Hall (see box, p. 23)— captures snapshots of the entire American political experience from 9/11 through August 2005? My Holy War is a kind of diary chronicling the shocks of our epoch: the attacks, George W. Bush’s assault on American democracy, our traumatized attempt to fathom the Islamists’ motives and divine their next target, the weird mirroring of Islamofascists by U.S. neo-Puritans, the false dawn of Howard Dean, and Bush’s ugly second coming. And it’s all very specifically described through the lens of the Seattle body politic. Instead of theorizing about the national mood the day after the election in the manner of standard gasbag national pundits, Jonathan Raban reports the immediate reactions of his friends and neighbors; instead of passively accepting big-picture notions like the red state–blue state schism, he relies on his own research and ramblings to recast the problem as a conflict between Seattle and the Twin Peaks countryside.

Raban is not large—he’s lean as a strip of buffalo meat—but he contains multitudes of contradictions. He covers the world war from the Queen Anne home front. He’s a backwater media critic chronically sought out by media monoliths—when Frank Rich wants to bash Bush, he reaches for the well-wrought truncheon of a Raban quote. Raban is bookish to the point of donnish abandon, yet his most biblio-bibulous lucubrations are anchored by global shoe-leather reporting going back a quarter-century.

Pigeonholed by many as a travel writer after his reputation-making 1979 Arabia: A Journey Through the Labyrinth and 1981’s Old Glory, a quirky, snarky account of his trip down the Mississippi River, he is, in fact, far more esoteric than even the most literary of conventional travel writers, like Jan Morris (and far more reliable than the most esoteric, like slippery Bruce Chatwin). Raban proves that travel needn’t be a confining aesthetic ghetto: His fellow best-selling eccentric globe-trotter Bill Bryson intensely envies Raban’s ability to describe each new wave of the sea in language that’s precise, original, and poetically right, and the British author Adam Nicolson has called Raban’s 1999 Passage to Juneau “a kind of anti-Odyssey” wherein Penelope gives the hero the heave-ho—and adds that Homer is a travel writer, too. If anything connects Raban with the mainstream, it’s the way he fulfills W.H. Auden’s crack about the genre: “It’s in keeping with the best traditions/For Travel Books to wander from the point.” Raban does so gloriously, constantly changing tack, yet with a sailor’s unerring sense for the utterly idiosyncratic literary destination he has in mind.

He also loathes being dubbed a regional writer, and he’s right. Granted, he has nailed the Northwest sense of place as well as anybody ever—Mary McCarthy, Betty MacDonald, Murray Morgan, Tom Robbins, David Guterson, Timothy Egan, Bruce Barcott—in prose more subtly sinewy than any of them (with the possible exception of Richard Hugo). “But he transcends the regional-writer rubric the way Faulkner did,” says former Amazon.com literature editor James Marcus. “He finds all the human qualities in his own backyard.” Except Faulkner was ineradicably rooted in Mississippi soil, while Raban is stateless in Seattle. That’s why he can see things the rest of us overlook.

Adds Marcus, “The guy in his novel Foreign Land spends 30 years running a ship bunker in Africa—a kind of offshore gas station for passing vessels. In other words, his business is talking to people who don’t set foot on dry land. And when he returns to England, he promptly buys a boat himself, and only there, as we’re told on the last page, is he home and dry. Well, that’s Jonathan’s MO. When I interviewed him in 1996, you could actually see his boat from his house, anchored at one end of the Ship Canal. That seemed like a necessity to him—a means of escape.”

Raban was stateless to start with. He hesitates even to specify which patch of English turf he springs from—his upbringing was peripatetic, and when he gazed at a stream by one of his childhood homes, he fantasized it was Huck Finn’s river. When he followed in Huck’s wake, the place became Raban’s and his alone. “What’s unusual is to have a regional writer be an outsider all the time,” says Marcus. Lots of Brit expatriates yearn for home, but when Raban’s fictional Brit returns after decades in Africa, the foreign land in question was England. The running gag in his homecoming memoir, Coasting, is that his old haunts in England are an alien place. His sole home is the here and now, of which he makes the reader an instant honorary citizen in scenes lit with pinpoint lightning.

A natural-born nature writer, Raban is still more attuned to what history and literature have to say about the scene he records. Wonderful writers like Ivan Doig privilege us to see through the eyes of historical witnesses, but Raban has a more complicated binocular historical vision. In Passage to Juneau, his own voyage parallels the 18th-century one of George Vancouver. Raban sees with Wordsworthian alertness to nature, while meditating on the way the same scenes appeared to the unliterary captain and his officers, who saw it through romantic-poetry-tinted glasses. Raban plunges into his own life’s inside passage and the inner lives of his predecessors. He seizes the day and puts it in the context of the sages of the ages, whose books tumble off his boat’s shelves in storms. Too many Northwest writers unreflectively succumb to nature porn—peaks ‘n’ grass as tits ‘n’ ass—but Raban is after bigger game. He reminds me of what William Gass said of Proust: “He returned to his childhood the way a modern primitive returns to the woods: with his books, his bankroll, and a stash of pot.” In Raban’s case, make that tobacco and a very nice bottle of wine. He braves the wilds on waves, sand, and pavement, but he’s always ensconced in his portable library, the teak one and the one in his skull.

On the other hand, I’m not sure he’s ever left his dad’s house. “Jonathan’s father was a pastor,” says Seattle writer David Shields, who faxes his own prizewinning work to Raban for endless editing, “and I think of JR as writing/delivering secular sermons. Dark, discomfiting, ambiguous moral parables of/for our time.” Raban clashed with his math-minded, military-vet, Church of England dad in the rebel 1960s, but the good man left his stamp. In school, the headmaster called Jonathan “Raban, Son of the Cloth.” When father and son had grown-up reunions, Raban writes, the two of them awkwardly “bobbed and weaved like image and essence in a looking glass.” Most leftist political writers write about Christianity with arrogant ignorance. When Raban writes in My Holy War about “Pastor Bush” and the religious right, he knows religion better than they do.

As Raban entertainingly relates in For Love and Money: Writing, Reading, Travelling, 1969–1987, the most ingeniously stitched-together journalism collection I’ve ever read, he pursued an academic career, acquired titanic mentors (Philip Larkin, Robert Lowell), impulsively told academe to stuff his pension, and became a freelance literary critic specializing in American writers, especially deracinated ones. He topped his 1968 book Mark Twain: Huckleberry Finn with his Huck-redux travel book Old Glory, winning permanent financial support for any trek he cared to immortalize. After Arabia and England, he chose to explore four distinct U.S. locales from Manhattan to Seattle in greater depth for his 1990 philosophical travel book Hunting Mr. Heartbreak: A Discovery of America. In Seattle, he discovered a literature-minded Seattle Weekly writer. They married and divorced, but their daughter kept him here.

What a piece of luck for us! A major writer of our time is forced to study our past and chronicle our present. But I think it was a major break for his work, too. The satire of American eccentrics in Old Glory is priceless, but naive compared to his later writing about wanderings with a compass set from Seattle. It’s more in the proud tradition of Britons ribbing us without totally understanding us. Both Old Glory and 1996’s Bad Land won the Thomas Cook travel-writing award, but the latter also won the National Book Critics Circle Award. OK, the former also won the Royal Society of Literature’s Heinemann Award, but I still think setting out from Seattle east past Montana somehow anchored and deepened his work.

Next came Passage to Juneau, a still more personal masterpiece, and 2003’s Waxwings, a novel about dot-com boomtown Seattle—an innocent world that now seems as remote as Vancouver’s voyages. His only prior novel, 1985’s Foreign Land, made a modest noise. But long residence (officially as a “resident alien”) in a foreign land won him more honor at home: Waxwings was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize, England’s (and probably the English-speaking world’s) most prestigious. Instead of simply skillfully skewering American types the way he did in Old Glory, he skewers us—those dot-com zillionaires party-hopping Lake Washington in float planes were pretty funny—and also mildly mocks his snooty immigrant protagonist, who’s sort of a cross between himself and an attitudinizing, vaguely Andrei Codrescu–ish radio commentator on American affairs. The pre-Seattle Raban was closer to that guy, making dismissive literary allusions and sniffing like a moralizing pastor. Maybe being a quasi-Seattleite—or a sort of satellite orbiting Seattleites—gave Raban perspective on the immigrant’s dilemma or mellowed him a little. On the other hand, maybe it was just time that did it—Raban’s pastor dad went liberal as he got older, too.

Pastor Raban the Younger can still write, in My Holy War, a hell of a brimstone sermon about liberals in the hands of an angry Bush. He’s “a bit over halfway through” his second Seattle novel, which now signifies not the lost dot-com paradise of the ’90s but the purgatorial, barbed-wire-festooned, right-wing-mind-forged-manacled, permanent-terror-alert Seattle of the day after tomorrow. He’ll finish by April Fools’ Day and publish on Sept. 20, 2006. And there’ll be a third Seattle novel after that.

If Raban thereupon wraps up the Seattle chapter of his life, as he says he probably will (see interview, next page), he’ll have done enough. He’s probably the most protean, least parochial chronicler we’ll ever have. One day he’ll sail away, but he’s like a pirate in reverse—he leaves the treasure behind.

Putting Seattle on the Map

Jonathan Raban explains why his adopted city is the ideal place for righting wrongs, writing novels—and terrorist bombs.

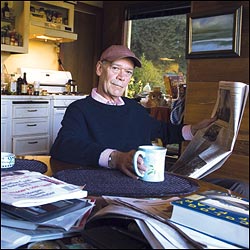

In his new book, Raban explores the “foreign” landscape of the post-9/11 world. (Rick Dahms) |

The following is an edited, condensed conversation between Jonathan Raban and Seattle Weekly’s senior arts writer, Tim Appelo.

Seattle Weekly: It seems to me that your work took a big turn right about 9/11.

Jonathan Raban: Yes, I think so. I think after 9/11 the politics of this administration could no longer be ignored. I’ve always been a somewhat political animal, though never for the far left, always sort of the wet center left. In 1989, the first year I ever visited Seattle, I published God, Man and Mrs. Thatcher. . . . I was in the same type of rage at society as I am now. I have to say I feel really nostalgic for the reign of Mrs. Thatcher, who seems so innocent compared with what’s going on now. But back then, I was in a state of total rage. . . . Consequently, it was pretty easy to move from England to the States. The liberal climate of Seattle seemed to be everything Thatcher seemed to be destroying in England.

The other turning point was when you moved here to write 1990’s Hunting Mr. Heartbreak.

Coming here was just accident. It seemed to me more like relocation than immigration. Tons of people move from, say, Boston or New York to here. The kind of leap they have to make is at least as great, if not greater, than the one I made coming from London.

Seattle isn’t big enough to be its own world. New York is provincial because you don’t need the rest of the world if you’ve got New York. I was bitter when forced to live in New York, and now I miss it. I’m always exiled. You don’t seem to be. You seem quite resident.

I do feel quite resident. I have one child who is now 12. She is my tie to this city. Whether I’d live here if she didn’t exist is an impossible question. I rather doubt it. I think that I’d probably be back in England, probably in London.

You write with a local point of view.

I think this is one of the big advantages one is sort of handed on a plate. From the perspective of London or New York or Washington, D.C., the temptation always is to adopt the assumption that you’re writing from the main center of the universe. The foreground is never questioned. People writing from Washington, D.C., don’t have to describe the architecture of Washington, D.C., before they start thinking about Iraq, but writing from the perspective of Seattle, you have to make plain where you’re coming from. You have to make plain the detachment, the provinciality, the preoccupations that affect the way that you think. So that Seattle itself has become, in this book, one of the central subjects.

If I were a terrorist, I’d take advantage of Seattle’s docks.

It’s the horrible proximity of the container port to the downtown. I once spent a gloomy Sunday afternoon with MapQuest: I started on the East Coast, through the Gulf, West Coast, seeing which container port was nearest to the city center. If you were setting off a bomb in a container aboard a ship, which port would you inevitably choose in order to get downtown from the docks? Most container ports are miles and miles away from the center. A good pitcher could throw a ball and hit Safeco stadium from Seattle’s container dock. If you were sitting in Indonesia wondering where to send your ship bomb, Seattle would look like a sitting duck.

I think Al Qaeda thinks of the U.S. as a montage of landmarks. That’s why they tried to blow up the Space Needle.

No, they didn’t. He just [planned to spend] the night in Seattle on his way to a much bigger target of LAX. Seattle’s narcissism had it that he was going to blow up the Space Needle.

We’re starved for attention, out on our floating patch far from America.

But not only from the rest of the United States, but out from eastern King County. Between liberal downtown Seattle and North Bend—it might be measured in terms of a thousand miles. We are just about exactly as far from North Bend as we are from anyplace you can name in Ohio. Our blue state–red state thing is complete fiction. It’s urban versus rural, and the moment you cross the bridge, either of the bridges over Lake Washington, you’re in Republican territory.

It’s a cultural divide.

There is a war in some ways more vital than Bush’s so-called War on Terror between countryside and city. When one talks about the great rift that sits at the center of American life, it is that urban-rural split. It is not that silly fiction of liberal activists who passed around that famous e-mail, you know, “The United States of Canada and Jesusland.” The blue coasts with the angry red heartland. It’s not that at all; it’s Seattle versus North Bend. London to Seattle was no great distance. Traveling from London to North Bend would have been a giant distance that would have turned me into an immigrant in a strange land, but Seattle has never really seemed that strange.

Did editors ever give you any whining about your local point of view?

Not at all, rather the reverse. Bob [Silvers, editor of The New York Review of Books, which published the essay on maritime terror] was saying, “All that stuff about Seattle was really interesting. We want more of that.” I tried to make Seattle real on the page for people who would be reading these pieces a million miles away.

To report the local polity’s reaction is reality-based in a way that the government is professedly not.

History will not be able to credit that after four years, a completely failed and inept invasion of Iraq, the worst foreign misadventure in modern times, that the Democratic Party ran last November under the flag of John Kerry. I mean how could this be? Last November’s election should have been a grand intellectual and ideological debate—and they ran John Kerry.

He’s the anti-Cicero. In the forthcoming second book in your trilogy of Seattle novels, I understand that there’s this frightening vision of the docks and Seattle as a security state.

It’s very much set in the middle of the War on Terror. And it’s not a trilogy. Because Seattle is a small town, it’s sort of inescapable to have one or two characters from Waxwings show up, like people do by coincidence, in the next book. Because that is sort of true to the nature of small towns and coincidences.

My Boy Scout camp counselor became Gov. [Gary] Locke.

Yes, exactly.

You said a cool thing once about Seattle being the size of London in Dickens’ time.

It was the critic Steven Marcus, I think, who long ago answered the popular complaint about Dickens’ novels being too full of coincidences by pointing out the demographics of London in the 1830s and ’40s. Its population was about 1.5 or 1.6 million—a huge city by the standards of that time, and I think the world’s biggest, but now no more than a mildly generous estimate of the population of Greater Seattle. Marcus argued (and backed up his case with statistics) that the chances of strangers bumping into each other, coincidences happening, were infinitely greater in Dickens’ little London. That’s why Seattle now strikes me as the perfect novel-sized city, made for plotty coincidences. More than that, Seattle has all of America’s heterogeneity and multicultural patchwork texture, but in a containable, describable space. I mean, you can see it all from the top of Queen Anne or Capitol Hill. How could one resist writing about this place?

But it’s not a trilogy?

They weren’t supposed to be a trilogy. That they were set in the Pacific Northwest was the only thing that bound them together. I thought, “This will probably keep me happily occupied in Seattle until my little Julia will go to college, and I sort of need to be writing about the Pacific Northwest as long as I’m here. Because this land will remain strange to me. I’m conscious of being a foreigner, which is a good thing. This is not my country, it’s not my culture, it’s not my accent, so there’s that constant rub between the inside of your head and the exterior world. It’s like sort of being perpetually traveling. I feel like I’ve been perpetually traveling for the last 15 years. Even the two travel books that I’ve published since I’ve been living here, Passage to Juneau and Bad Land, were both about the neighborhood. Seattle is as interesting as anywhere else in the United States, and novels have to be about someplace—why not Seattle? It’s relatively fresh terrain, it hasn’t been done by too many people before. America seen from and in Seattle is a different America than seen from and in New York or Mississippi. But no less valid. I think there is still a sort of sexiness about the Pacific Northwest.

You mean because of its pop culture?

People in England or people on the East Coast of the United States have an interest in Seattle and this region that Seattle tends to forget about. I met a woman in Missoula who regularly got her hair done in Seattle. Five hundred miles for a hair-cutting job. If you wanted to go to a major-league game, you’d go to Seattle. If you wanted to see a major theatrical production, you’d go to Seattle. When writing Bad Land, I moved a whole lot further east, to the border of eastern Montana and western North Dakota. I’d be in North Dakota and meet Mariners fans. Seattle is the capital city of a gigantic, underpopulated region, which stretches east past the Cascades, past the Rockies, and you can still feel the magnetic tug of Seattle when you’re a thousand miles east of here. So I think Seattle banging on about its own provinciality is tiresome.

Jeff Ament of Pearl Jam was bitter about his parents making him grow up in Missoula—or, as he put it, “Bum Fuck, Mont.”

Bum Fuck, Mont.? Missoula! Bum Fuck! Missoula is, as it were, Paris, Mont.

But the minute he could, he beat feet to Seattle for his career, and that’s an example of what you’re saying. And yet, Seattle doesn’t look beyond itself. Seattle is barely conscious of Bremerton. If you move to Bremerton, your friends aren’t going to come to your house for a party. There be dragons!

Bainbridge is part of Seattle, but Bremerton is out there somewhere. Bremerton is Seattle’s Jersey. Only there ain’t no bridge or tunnel to Bremerton.

I wonder whether there is some kind of continuity between modern Seattle culture and the original culture. I think Tom Robbins said that the Indians used to have longhouses to get out of the rain, and what were they to do but devise the greatest legendary culture, according to Claude Levi-Strauss. So what do we do? Put screens at the end of longhouses and watch movies. Are we following in footsteps of people we don’t remember?

I think that the one power that comes instantly to mind is that Indian villages faced on the water. And you regarded the nature that lay in back of you, the woods, as being full of danger, and you looked at the water as being kind of this street, with which you traded with other villages, using water as a town square. That, I think, has survived. And looking to trade by water is essentially how Seattle makes its money.

Seattle has a rich cultural past, but not much literary tradition. Why set a novel here?

I don’t think particular places each need their own literary tradition. The tradition’s in the language, surely, not the place. I’ve always been interested in the tradition of the city novel, from Dickens and Thackeray to Bellow and Martin Amis and many others. Doesn’t Bellow’s Chicago owe quite a bit to Dickens’ London? Trying to write about Seattle, I find the shades at my elbow aren’t local ones like Richard Hugo, whose work I much admire (who doesn’t?) so much as the writers I’ve been reading all my life—Thackeray, Dickens, Evelyn Waugh, Bellow, Malamud (whose The Assistant is a great city novel, and whose short stories set in Brooklyn knock my socks off). James’ Washington Square, Trollope’s London novels in the Palliser series. . . . I think these are as much a part of Seattle’s literary tradition, our English-language literary tradition, as any book with Pike Place Market in it.

If you’re a regional writer, where’s your region?

Where’s my region? I think many of us carry a sense of our own displacement with us as if it were a region. Being not from here is a way of being as distinct as being from Aberdeen, Wash., or Oxford, Miss., or Lower Grimsdike, Yorks. It’s partly why I liked living in London and like living in Seattle—both cities in which most people aren’t from there. I can never give a straight answer to the question of where I come from in England. I have to mumble something about how my parents moved around a lot (they did), and how I spent many more years in London than I did anywhere else, nearly always in the company of other people who “came from” elsewhere. And so it is here—one or two people I know are lifelong locals, but most are migrant birds like me. Perhaps I have a slight edge on my friends in being Brit to boot—a further degree of elsewhereness.

I wonder if your only real home is your boat, wherever it may be. Are you perhaps the anti–Philip Larkin? There’s a great scene in Coasting, your memoir about sailing around England, where you reunite with Larkin, your college mentor. After some drinking, you attempted to coax the 230-pound refusenik poet laureate, whom you once called a “shifting liquid cargo,” onto your boat. But besides wisely sizing up the odds that you would be able to save him if he fell off the boat’s ladder, he was aggressively rambling-averse and perversely rooted. He clung to his local habitation. Aren’t you the opposite? I’ll bet you couldn’t feel at home unless your boat was ever ready to free you from it.

Do you know his poem “The Importance of Elsewhere”? He was a migrant—Coventry, Oxford, Leicester, Belfast, Hull. I wouldn’t quite call Hull his local habitation. It was a temporary perch that accident solidified into permanence, of a sort. . . . Certainly, I’m a lot more physically and constitutionally mobile than Larkin was and have never remotely shared his famous loathing of “abroad.” I like abroad in both its senses—being on the move and being in a country foreign to me. In the intro to My Holy War, I wrote something about America never being more foreign to me than it is now—something that makes it sort of more attractive to me, not less, if I’m honest. It’s true that I used to see my boat as a sort of private floating state, but not any more. An occasional means of temporary escape is all. A vacation vehicle in which to potter around the Gulf Islands. . . .

[Later, Raban got to thinking about that line he used about Larkin’s “temporary perch that accident solidified into permanence, of a sort.” He e-mailed me: “I realise now that I was describing my Seattle. . . . “]