Crave

Little Theatre; ends Mon., Oct. 3

British playwright Sarah Kane was plagued by harrowing introspection and self-loathing and worries about the world until she finally hung herself by some shoelaces at the age of 28. And, sorry to disappoint the estimable Harold Pinter and her many other defenders, but the supposed pinnacle of her pain is a wank of a work that barely qualifies as a play, or even enough reason to spend its scant 45-minute running time in a theater.

Man, does Washington Ensemble Theatre (WET) make the most of it, though. Crave had its Seattle premiere nearly three years ago in VIA’s chic, snarling, but unavoidably empty production at the East Hall Theater that efficiently left no reason for anyone to want to see it again; WET sloshes into the text undaunted, beginning with a technical excellence that is—almost— reason enough to submit yourself to what is essentially Kane’s extended, obsessive-compulsive suicide note.

Scenic designer Jennifer Zeyl, whose ardent inspirations have previously been the company’s saving grace (witness the winsome, grassy playhouse of the otherwise insufferably precious Handcuff Girl Saves the World), officially deserves a raise for her efforts here. A long, wide rectangular window slides open on an imposing black wall just enough to reveal the upper bodies of the ensemble—Mikano Fukaya, Marc Kenison, Lathrop Walker, and Marya Sea Kaminski (whose panicked, despondent face could wrench the stoniest heart)—trapped between three white walls that are covered in some ungodly transmogrification of those popcorn-covered ceilings so popular in the 1970s. Jean-Paul Sartre must be snickering wherever he is, waiting to shake Zeyl’s hand for so cunningly capturing a peep-show purgatory with no exit. As lighted by Jessica Trundy to play off the pale of both the set and Heidi Ganser’s smartly colorless, antiseptically formal costumes, this eerie void looks as though it’s seconds away from either burning up or solidifying into an eternal frost. When, halfway through, the unseen floor of Zeyl’s nebulous cavern fills with water, casting wavering shadows of illumination on the walls and drenching the actors to their skin, you wish that what the performers had to enact wasn’t as shallow as the pool in which they are so eagerly wading.

Director Roger Bennington is smart enough to use the environment for all it’s worth, though, posing his people in silent, sullen, austere stage pictures before breaking them off into the kinds of spastic physical extremities that most sensible people fear when they hear the words “experimental theater.” Bennington is determined to make something of what he’s got, and he does—the actors convincingly come at us like souls in torment, ranting and railing against the world, themselves, and each other. They’re crying out Kane’s sometimes stirring and rhapsodic but more often monotonous laundry list of random despair, while flailing about in an angry ecstasy: “Nothing. Nothing. I feel nothing.” “No one can hate me more than I hate myself.” “The heart is going out of me.” “I hate these words that won’t let me die!” The actors drop out of sight, then return shaking and dripping with water. (A sharply choreographed sequence of their wet heads bobbing in and out of view comes brave millimeters away from knocking at your funny bone; it looks like synchronized swimming.) You’ve got to hand it to everybody involved for thinking that Kane had Something to Say.

And she did—but it’s too often pretentious, and only superficially intense, and, sadly, better shared with a sympathetic therapist than strung together into a “script,” nonlinear or no. STEVE WIECKING

Once On This Island

Village Theatre; ends Sun., Oct. 23

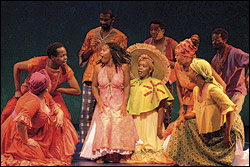

Almost everything that should make for heart tugging in Lynn Ahrens and Stephen Flaherty’s (Ragtime) Broadway musical is in full supply—star-crossed lovers, romantic sacrifice, enraging racial inequities, the enduring salvation of storytelling. And director David Bennett, who staged an elegantly unfussy My Fair Lady for the 5th Avenue in 2003, has at his disposal a fresh cast of singers to put it across. Yet the show feels flat and can’t sustain its brief hour-and-a-half running time. Ahrens’ book, based on Rosa Guy’s novel My Love, My Love, is a Caribbean take on Hans Christian Andersen’s plaintively beautiful The Little Mermaid, but the Village Theatre’s listless version doesn’t quite muster even the simple colors of the Disney cartoon.

At first it looks—and, especially, sounds—as though it will. In a vibrant prologue bursting with Deb Trout’s bright costumes, dark-skinned orphan Ti Moune (Alexandria Gray) is rescued from a flood by four gods, who place her in the hands of a loving older couple, then continue to play with her fate when she falls for a privileged young mulatto from the other side of the island. Desperate to nurse the wounded, unconscious Daniel (David Devine) back to health, Ti Moune (Lisa Estridge), now a grown woman, promises Papa Ge (Ty Willis), the God of Death, her soul in return for Daniel’s well-being—and what she wrongfully assumes will be a life lived happily ever after.

This is four-hankie material, with the Ahrens/Flaherty score alternately aiming for tears of sorrow and celebration. The voices here deliver—Charlie Parker fairly glows as Erzulie, the Goddess of Love—but, rather disappointingly, the bodies do not. One of the motifs of the show is a happy, soulful “We Dance,” and, well, they don’t. Though Bennett has his villagers catcalling as if they’re really whooping it up, they’re moving not nearly enough—and not very well. Those that can, do, but it’s clear that Bennett chose singers over anything else; Timothy McCuen Piggee, in commanding voice as Agwe, the God of Water, has two large left feet that leave him trying to distract us with flourishes of his sea-colored cape. When Ti Moune is supposed to astonish some rarefied guests at one of Daniel’s parties with a joyful release at the center of the dance floor, Estridge’s unimpressive boogie makes it hard to comprehend what all the fuss is about.

Even with more capable practitioners, however, Chris Daigre’s choreography wouldn’t fill in the rest of the fluid, magical universe that Bennett has tried to create. The numbers all look the same—rhythmic circles swaying to the beat— and don’t have the lift of the buoyant, passionate vocal work. As the heroine’s adoptive parents, T. Edwin Pettiford and Faith Bennett are, in their songs, suffused with an evolving, organic emotion that Daigre’s contributions lack (their weeping farewell to a daughter they’ve made their own is the evening’s high point).

Estridge, though an attractive, powerful singer, is another liability. Her wide-eyed, high-pitched, nasal affectation of youthfulness doesn’t register credibly; she’s too old to play an ingenue, and overpowers the character’s supposed innocence.

If you close your eyes, you can hear suggestions of this Island‘s ample wonders. Once you open them again, unfortunately, most of the magic fizzles. STEVE WIECKING