Until last week, Norm Maleng, the seven-term King County prosecutor, had never filed charges against Frank Colacurcio Sr., who, for 62 years—starting when Maleng was 3—has been on a path to becoming Seattle’s modest version of an organized criminal. “No,” Maleng said, strolling down an office hallway in the King County Courthouse. He had just charged Colacurcio and three others in the Strippergate case with nine criminal counts that included conspiracy. “It was always federal,” Maleng said. “Remember, it was back in the ’50s and ’60s, I think, the early ’70s, and it was federal, and if memory serves me, it was mostly income tax.” This time, it’s political money laundering. The latest charges are the result of a two-year city and state investigation into $39,000 that Colacurcio and others allegedly doled out in secret to the re-election campaigns of three Seattle City Council members.

Of course, Maleng, 65, knows the name Colacurcio. It was in all the papers. The nude-dance king, 88 as of last month, has been to prison six times—for criminal racketeering and tax skimming, among other weaknesses—starting in 1943, when the then-25-year-old Bellevue truck farmer served two years for carnal knowledge of a girl, 16. One of Maleng’s predecessors did the prosecutorial honors then. After that, Colacurcio moved on to the big time, U.S. District Court, up the hill. Maleng says that, of course, Colacurcio’s history did not play into the latest charges. “But,” he said, stopping in the hallway, “everybody brings to the table what they have done, if you know what I mean.”

The stripper king knows, though he never seemed to take his sentences too seriously. He once said the worst thing about prison wasn’t the time or the food but the women—there just weren’t any. Like his first crime seven decades ago, the latest crime of which he is convicted involves a woman: Unrelated to Strippergate, Colacurcio was recently found guilty in Seattle Municipal Court of groping one of the waitresses at Rick’s, his club in North Seattle. He is appealing. She is suing.

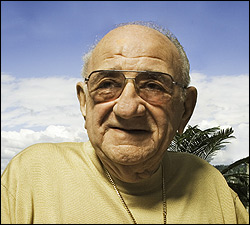

With this sort of experience, the graying, stocky Colacurcio knows when to pipe up or down. At his nice home with the pool at the north end of Lake Washington, he was answering the phone the other day and saying little about the charges Maleng filed over the campaign contributions. “Thing is, until this thing is over, I can’t talk about it,” he said when asked his reaction to the money-laundering charges against him, his club-manager son Frankie, 43, and two employees, ex–lounge musician Gil Conte, 71, and office manager Marsha Furfaro, 65. They are accused of washing a series of donations through the accounts of a dozen friends and associates and into the 2003 council campaigns of Jim Compton, Heidi Wills, and Judy Nicastro, who, Maleng says, were unaware of the conspiracy. “Really, you have to talk to my attorney,” Colacurcio said pleasantly. Attorney Irwin Schwartz, in a statement, said Colacurcio plans to fight the charges. His son, Conte, and Furfaro all pleaded not guilty on Tuesday, July 19. Colacurcio, said by his family to be recovering from emergency surgery, is set to be arraigned Aug. 1.

One of Colacurcio’s old family friends, former Gov. Al Rosellini, a political-money rainmaker who was thought to have helped pass along funds to the council members, was not charged. “There is no evidence of any criminal wrongdoing” by Big Al, says Maleng. Though the investigation continues, Maleng thinks he has the goods on the others, issuing 19 pages of charges and supporting documents. They outline an extensive probe into bank transactions and Colacurcio’s own business records, forming a long money trail that was blazed in search of a small favor from City Hall: a parking-lot land-use change at Rick’s. “It’s déjà vu all over,” says Tim Burgess, a former cop and ex–city ethics commissioner who remembers Frank back when. But, Burgess says, “it’s not about nude dancing or that stuff, it’s all about corrupt influence and using money to impact public life for private gain.”

The Colacurcios wanted the eight-stall lot rezoned for more parking at recently expanded Rick’s, on Lake City Way Northeast. The land use was approved, even after the contributions had been revealed in detail by the media (see “The Strip Club Connection,” July 23, 2003). The “conspiracy was centered around enterprises operated by the Colacurcio family,” Maleng says. Though the city’s elections probe hit a dead end, Maleng says he was able to bring criminal charges in large part by granting immunity to some of those involved—in one case, perhaps dividing a family. According to charging papers, and as first reported by Seattle Weekly in 2003, Furfaro’s daughters told investigators they were reimbursed for their contributions by their mother, the office manager at Talents West, Colacurcio’s strip-club employment agency. (Furfaro claims the funds tracked to her bank account came from a midyear “bonus” from the Colacurcios.) Others who may have donated Colacurcio-provided cash include John Rosellini, son of ex-Gov. Rosellini, says Maleng. While not charged, the Governor, as the elder Rosellini prefers to be called, was at a Tacoma casino with Colacurcio and a third man when one council contributor, longtime Tacoma civic figure Stan Nacarrato, was reimbursed. Nacarrato, now 77, can’t remember which one gave him the money, Maleng says.