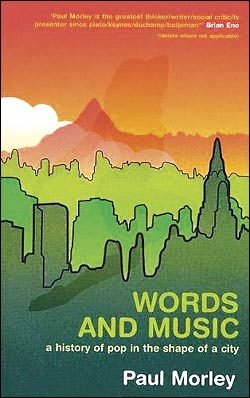

“L.I.S. and T. are the first four letters in ‘listen,'” Paul Morley declares near the end of Words and Music: A History of Pop in the Shape of a City (University of Georgia Press, $24.95), his wonderful mess of a book. Morley is an obsessive list maker, and a great listener. As a pop critic in the U.K. in the late ’70s and early ’80s, he produced some extraordinary experimental writing—extraordinary mostly for the substance beneath its postmodernist playfulness: an unbreakable grip on sound and its history, and slippery insights into the slipperier matters of image that make sound and its history, as such, impossible to grasp firmly.

Then he slipped inside the machine he’d been documenting and co-founded the Zang Tuum Tumb label with producer Trevor Horn in 1983. (The Art of Noise, of which Morley was something like a member, was essentially the image of a group without a group.) Morley assembled ZTT’s daffy, confounding liner notes, and he’s written a few essays about other musicians over the last 20 years (notably his North Star of music and conceptual art, Brian Eno), but not a lot. So Words and Music is his return to mapping the sound and vision of pop and antipop, mostly from the inside of a car he imagines speeding down Kraftwerk’s autobahn. The words spill out like he’s been saving them up for decades.

The book is nominally about Kylie Minogue’s hermetically invulnerable pop song “Can’t Get You Out of My Head” and Alvin Lucier’s infinitely degradable experimental-music landmark “I Am Sitting in a Room”: opposite terminal points on a continuum for which Morley proceeds to propose a few hundred alternate pairs of opposite terminal points. Lucier’s presence in the book is gradually diffused, like his voice on his recording; Kylie, though, stays front and center—Morley suggests that Words and Music might have started its life as a conversation about an authorized Kylie bio.

He speeds her car through a hailstorm of references to records he can’t possibly assume his readers have heard, with occasional digressions: an interview with Jarvis Cocker; six pages of one-clause paragraphs about (but not directly mentioning) Manic Street Preachers that all begin, “As Welsh as . . . “; and a weirdly adorable assessment of his own place in the hierarchy of music criticism (“I remember the moment I knocked out Nick Kent, with a flash of inspiration about Devo, and the moment I dismissed Charles Shaar Murray, with a double whammy of insight regarding Joy Division and U2”).

The Minogue/Lucier narrativedoesn’t exactly have a resolution: Mostly, it’s an excuse for Morley to riff and vamp, to show off his chops as a writer. A love scene involving Kylie and the Japanese assault-noise master Masami Akita, aka Merzbow: “Masami loves the way she smells, like metal petals embedded at the centre of the moon . . . their kiss is remixed—for him, by Autechre; for her, by the Pet Shop Boys. . . . ” On Captain Beefheart: ” . . . [F]or starters imagine the blues, only green. Imagine rock and roll, only it’s more wriggle and jerk. Imagine jazz, possibly quite free, only it’s jazzzz, and it’s freeeeee, or, to be more scientifically accurate about it, zazzjzz and eerereef.” There are out-of-nowhere rhymes, alliterations, and brilliant rants about New Order’s “Blue Monday,” covers of “Satisfaction,” and the Michael Jackson/Lisa Marie Presley wedding (“for $300 million you would be able to buy the marriage, frame it, and hang it on your wall”). Morley is the crazy limo driver; you can tense up, or you can sink into the upholstery and go where he’s going.

One recurring feature of Words and Music is a time line of human evolution, naturally featuring as its pinnacles the birth of Kylie Minogue and the release of “Can’t Get You Out of My Head.” By the early ’60s, it’s a relatively straightforward chronology of adventurous pop and other landmarks of modernity. Then 1963 includes, between the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” and the Surfaris’ “Wipe Out,” the White Stripes’ Elephant, with a little essay about how important it was and how earth-shattering it sounded in 1963, and how great it still sounds now. Well, of course.

At the end, Words and Music collapses into a slippery mound of lists: favorite-record charts and descriptions of books Morley might have written but didn’t (“1,100 words on each of 121 songs that explain why Kraftwerk are Kraftwerk and just how and where and when their influence spread and turned”), riddled with typos and errors and records too fantastic to exist. Most of Morley’s lists, though, aren’t just showing off the breadth of his collection and taste. Every record he pulls down from his shelf is something he desperately wants you to listen to, because it adds incrementally to the scale of what he’s talking about. That’s what he means by “the shape of a city,” and why he’s drawn to the postmodern 20th century and its mosaics of fragments. A top-10 list is only itself; a list of 100 records is only a snapshot; but if the lists and lists of lists get big enough, then you have to observe them from a distance, and when you get far enough away, they become a man-made landscape, sculpted and crawling with life, so big that the only way to begin to understand it is to start listening right now.