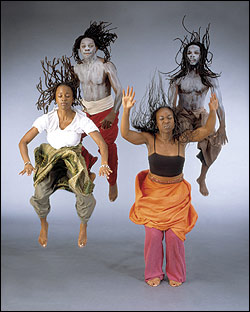

Facing Mekka, which Rennie Harris and his Puremovement company will perform at the Moore Theatre (Fri., Jan. 28–Sat., Jan. 29; 206-292-ARTS), took about six years of work. Fitted between other obligations, it was originally designed to take up where Harris’ Rome and Jewels left off. That revisioning of Romeo and Juliet, seen in workshop form at On the Boards, drew connections between Shakespeare’s text and the competitive structure of break-dance, but the new piece turns away from that perspective.

“Originally, Mekka was the place where Rome would end up—I thought that was going to be it,” Harris explains. “But as I got further into Mekka, it became a totally different work. [It] became the idea of facing the truth within yourself. Our problems are not with other people—our problems are with ourselves. Until we figure that out, we won’t be able to move forward spiritually.”

Despite its title and the ironic fact that it premiered the first week of the Iraq war, Mekka isn’t about specific world events. Harris had planned the dance as a grand investigation of the roots of hip-hop, with trips to Africa and references to other fusion styles like capoeira, but in the end, it became a more personal project.

“It got on paper because [people] wanted to know: ‘Rennie, what do you want to do next?'” he recalls. “So that became a narrative to raise money for the piece. But I decided, ‘I don’t want to go to Morocco, I don’t want to do all that stuff, I just want to create the work.’ Hip-hop is a natural extension of African dance and culture, and I just want to get into the memory of it—I’m going to deconstruct it, so when you see it, it’s going to challenge anyone to tell me, ‘Is it hip-hop?'”

“What is hip-hop?” is a tender question for Harris. The stereotype, emphasizing the physical thrill ride, can sometimes overwhelm the meaning of the work.

“Because people have already been conditioned to think they know what hip-hop is, all they see is tricks,” he bristles. “That’s what they go to see—the virtuosity. But when I performed the solo Endangered Species in Seattle, no one talked about it. No one talked about March of the Ant Men. These are works that are specifically not virtuoso works, but they are strong works. I never really think about the physicality of it first, because it’s never really about that for us—it’s the pure joy of reaching ecstasy in a dance. People don’t understand that hip-hop became a kind of rite of passage for some people: I’m standing on one hand because my mind, body, and soul are physically in tune; if I wasn’t spiritually right, I couldn’t do what I’m doing. So, on some level, [the dancers] have to be in tune with the universe to be able to do what they do.”

In Mekka and in Lorenzo’s Oil, his solo on the same program, Harris is trying to do what most artists do—communicate something profound to his audience—but the fact that he comes from the hip-hop world gives him a set of preconceptions to work against. Although the expectations have irritated him enough to think about giving up (“I’ve tried to quit four times already! I’m frustrated with people and their need to think there’s never enough”), he still finds enough inspiration in the work to persevere.

“People applaud when they see one of the guys do something on the floor— it may not be dynamic, but as soon as that happens it’s, ‘Ooooh!'” he says. “Which is cool, but I can’t make people see what we see. That’s why I had to give that [idea] up—they came to see what they’re going to see. When Rennie Harris Puremovement evolved in 1990, that allowed me to do what I wanted to do. As long as I’m inspired, I’ll keep doing it.”