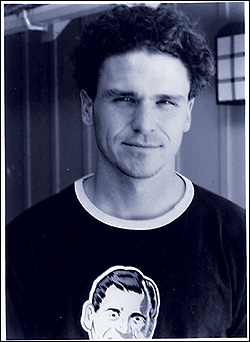

Keep it short. That’s the best advice any editor can give to a writer, and it’s probably also one of the signal criteria in two recent anthologies bearing the stamp of Dave Eggers and his McSweeney’s literary cartel. Attention spans are short enough so far as readers are concerned; we want our subjects tailored for bus or subway rides. The contributors evidently feel the same way in Created in Darkness by Troubled Americans: The Best of McSweeney’s Humor Category (Knopf, $16.95), since much of their work here may have been created on PalmPilots, cell-phone text messages, envelope backs, or in self-addressed e-mail hidden behind a decoy spreadsheet at work. It’s humor-on-the-fly, meant to be read almost at a glance, the stepchild of stand-up and channel surfing.

No surprise that lists are a staple (as on the McSweeney’s Web site from which they’re culled); they even get their own separate section. The 70-odd writers collected in the book probably all revere Letterman’s top-10 lists like Moses’ stone tablets. An entire generation has now grown up without the “A man walks into a bar” setup and proceeded straight to the part where everyone tries to one-up the original punch line. So we have “Not Very Scary Movies” (e.g., Friday the 11th), “Rapper or Toiletry?” (Cool Breeze), and “Films About Tough Jews” (Casino and The Ten Commandments . . . that’s all there is). From industrious local list maker John Moe, there are “As a Porn Titler, I May Lack Promise” (American History XXX), and “Cancelled Regional Morning TV Shows” (Tulsa Kills Itself), and Music Industry Trends Not Yet Overexposed (Gangsta Polka), among others.

The long-form stuff is more hit and miss. At the top is Jeff Alexander and Tom Bissell’s goof on DVD commentary tracks, in which Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky analyze the first Lord of the Rings movie. (Chomsky: “I think the Hobbits are criminals, essentially.” Zinn: “So is Frodo the Mohammed Atta figure in this story?”) Greg Purcell riffs nicely on an insane old Ezra Pound railing against modern culture. (He begs Billy Wilder to cast Charlton Heston, not Jack Lemmon, in a planned adaptation of The Aeneid.) As usual, Neal Pollack is not funny.

Throughout, you get the sense that the Web is not only the intended publishing outlet, but also the preferred research tool, as in the list “Good Westerns, Not Porn.” Thanks to the miracle of IMDb.com, we can ascertain that there really was a movie called Rimfire back in 1949. With a cute, random premise and broadband, it turns out that you, too, can be a writer. Now just make sure you’ve got that spreadsheet ready to hit Alt-Tab in case your boss walks by.

MORE WORK is required in The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2004 (Houghton Mifflin, $27.50), also edited by Eggers. The two dozen selections here include bigger names (like Christopher Buckley, David Mamet, and David Sedaris) and come from sources like The New Yorker, The New York Times, and Esquire—not your puny little Web sites. And you can bet these contributors aren’t working day jobs to support their prose.

Comic-book artists including Sammy Harkham (“Poor Sailor”) also make the cut, which helps break up the somewhat overearnest collection. Most are fiction, and most I found rather weak. Current cultural connections make the nonfiction stuff more interesting. Michael Paterniti’s “The Fifteen-Year Layover” helps shed some background light on the Steven Spielberg–Tom Hanks movie The Terminal. But it also makes the case that the actual Iranian expat self-stranded in a Paris airport would’ve made for a more worthwhile documentary.

Michael Hall’s “Running for His Life” nicely personalizes the Hutu-Tutsi genocide in Burundi from the perspective of distance runner Gilbert Tuhaboyne, now living in Austin, Texas. We learn how he narrowly escaped being burned alive, despite horrific injuries, then earned a track scholarship in the U.S. The compelling story of this one immigrant, uneasily settled but embraced by his new community, shows how conflicted this country is about its foreign policy and immigration policy. Most Americans simply turned the page when it came to the ’90s horrors of Burundi and Rwanda, though over 1 million died, yet they’re profoundly welcoming to the individual lifted out of the newsprint. One wonders if Iraq will be any different.

For political reasons, the sharpest entry in the book is Mamet’s language essay “Secret Names,” which proceeds logically from the linguistic taboos and investitures of nicknames and pet names to an Orwellian analysis of political speech. It’s a short distance from the Sultan of Swat to the Department of Homeland Security. Of America, he argues, “None of us has ever referred to our country as The Homeland. It is a European construction, as Die Heimat, or The Motherland, or Das Vaterland. And as it rings false, we, correctly or not, will question the motives of those who created it for our benefit. As we do the ‘coalition of the willing.'”

All we need is a list of such dubious phrases, and it’ll probably make it into next year’s McSweeney’s humor anthology.