Bill Condon is an old hand on Hollywood’s eccentric-sex beat. He earned a screenplay Oscar for Gods and Monsters, the brilliant biopic about director James Whale, who gave Frankenstein a queer-eye-for-the-undead-guy movie makeover. Now he unveils his naked-truth portrait of the big sexual enchilada in Kinsey (which opens Friday, Nov. 19, at the Egyptian). Alfred Kinsey (1894–1956) was the pioneering scientist whose epic study Sexual Behavior in the Human Male hit the nation like a sociological nuke in 1948. Who knew 95 percent of American men had violated at least one sex law on the books? Or that there were so many gay folks, virtueless virgins, and rural sheep-schtuppers?

Nobody, until Kinsey’s candid interviews with 18,000 indiscreet citizens blew the whistle on the American bedroom. The Kinsey Report, as a gob-smacked public called it, whisked the mild-mannered Midwestern professor to the best-seller list and the cover of Time. But when he released the 1953 companion volume on female sexuality, he got in big trouble. Who wanted to know that 62 percent of nice girls masturbated, or that most brides had achieved orgasm long before the wedding night by perversely diverse means Kinsey was only too happy to detail?

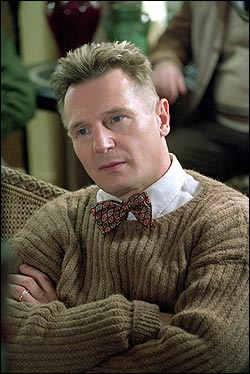

Writer-director Condon portrays Kinsey as anything but a disinterested scientist uncovering facts where they lay. He’s a hanky-panky evangelist. Liam Neeson is ideal to play the bow-tied, buttoned-down man who unbuttoned a nation. He blends towering monomaniacal passion with a cold remoteness, as the sex professor did. Condon depicts Kinsey as the spitting mirror image of his hellfire-preaching Sunday schoolmaster daddy (John Lithgow, far more moving than he was in his superficially similar bluenose-pop role in Footloose). Screwed over by his own repressive upbringing, Kinsey senior warns that the zipper is the devil’s invention, giving “speedy access to moral oblivion.” Son Alfred’s surveys gave Americans speedy access to the zipless fuck of their choice.

Laura Linney outperforms Neeson as Mrs. Kinsey, his former student and tireless academic ally. Not only did she help him professionally, she pitched right in putting Kinsey’s ideas into practice. Years after his death, the Kinsey Institute abashedly confessed that, yes, his circle was a nonstop orgy among nerds. (See T.C. Boyle’s recent novel The Inner Circle for a fictionalized treatment of the same promiscuous milieu.) Kinsey sampled both sexes and sundry oddball acts. Mrs. Kinsey, despite being a loyal wife (and remarkably homely—Linney fought the director to make her more so), hopped from bed to bed with mattress-back abandon. They would share conquests like tweedy forerunners of David and Angie Bowie. (Skyrocketing supporting actor Peter Sarsgaard sizzles as a Kinsey team researcher who found it a pleasure to work under both Mr. and Mrs. Kinsey.) Sex aside, she was the most beloved figure on the scene. Her social graces mitigated his clueless tendency to alienate people by talking at them like mere specimens to be studied. Fresh from starring as man and wife on Broadway in The Crucible, Neeson and Linney score the year’s most convincing portrait of a marriage, however peculiar.

Rich costumes, jazzy set design, alert cinematography, smart dialogue, and evocative period tunes delightfully transport us back half a century, and the huge cast does its stuff with brio. This brings up one of the movie’s two big problems. There are more than a hundred speaking parts. The countless interviewees singing the body electric overpopulate the picture. Many scenes are teases: When we walk into a gay bar frequented by Gore Vidal’s glittering cronies, we want to linger, listen, and watch. Condon whisks us in and out, as if conducting one of those quickie 12-capitals-in-six-days tours of Europe. There’s little sense of connection from one bit to another. Except for the climactic, virtuosically operatic monologue by Lynn Redgrave (Neeson’s aunt-in-law) as a lesbian saved from suicide by the Kinsey Report, and a particularly horrifying pedophile (William Sadler), few interviewees really get a chance to register.

Even Kinsey’s inner circle gets short shrift. Sarsgaard comes off as a bright boy toy with a nice tush but no motives. Chris O’Donnell and Tim Hutton sketch the perils of wife-swapping researchers so fast we barely know they’re there. Only the Kinseys are fleshed out, and less so than in a film without a cast of hundreds. When, late in life, he mutilates his own genitals, we can’t imagine why.

Condon’s film throws lots of stylish light on sex. But he leaves too much of Kinsey’s soul in the closet.