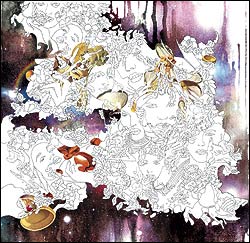

DYKEHOUSE

Midrange

(Ghostly International)

Midrange makes mid-’90s miserablism into a picture book. Where Slowdive wailed their guitars and the Jesus and Mary Chain spread distortion like honey over Tin Pan Alley hooks, Mike Dykehouse wanders through slow- simmering shoegazer with a curator’s eye— taking some of this and a little of that for a one-off exhibit of the genre’s best. The Vangelis-style aeroglide into the album’s sweeping synth pop is Dykehouse’s sci-fi overture, landing amid the Echo and the Bunnymen–style psychedelia of “Signal Crossing.” Fans of Dykehouse’s 2001 Dynamic Obsolescence, a more traditional electronic album along the lines of Boards of Canada, can be mock- horrified that Dykehouse apes Bilinda Butcher’s and Kevin Shields’ (both of My Bloody Valentine) vocals as if swallowing the prepubescent style whole. As with Shields, sex is both a mess and a sacrament, and the acid-stretch guitar sound of “When You Come,” like MBV’s “Cupid Come,” serves as a bed for the singer. The difference is that when Dykehouse sings in the present tense, it sounds like the loving happened long ago. Perhaps making Midrange helped him dredge memory from a time of innocence. Such sentimentality could be poison were “Chain Smoking” not the album’s fulcrum. This Magnetic Fields–style cynic-pop song includes the line “When we made out in your backyard/I tried to undo your pants and ended up crushing your plants.” Somewhere in Kalamazoo, a woman is blushing. DAPHNE CARR

LOLA RAY

I Don’t Know You

(DC Flag/Red Ink)

Now that every rap star with a hit in rotation has been awarded his own major-label vanity imprint, record-biz honchos are beginning to invite guys in pop-punk bands to wade through the towering piles of unsolicited demo CDs clogging mailrooms coast to coast. Blink-182 drummer Travis Barker just released a CD by a California screamo outfit called the Kinison on his Atlantic-distributed LaSalle Records; this debut by New York’s Lola Ray comes courtesy of Benji and Joel Madden, the twin brothers who front Good Charlotte and now run the Sony-linked DC Flag. It’s easy to hear what the Maddens liked about the disc, which Lola Ray singer-guitarist John Balicanta slipped Benji when Balicanta tagged along as his manager loaned Benji an acoustic guitar: Like those platinum-plated punks, Balicanta uses cleaned-up guitar fuzz as a way to make weepy emo-boy sentiments safe for the mosh pit, and he sports a fascination with zippy ’80s new wave that brings the mosh pit to it. Unlike Good Charlotte, Lola Ray aren’t very funny; Balicanta evokes “the end of the world” in “Automatic Girl,” and files a report from “the bottom of a wishing well” in “Plague (We Need No Victims).” But when they aim for wound-tight teen-dream drama, as in “She’s a Tiger” and “Charlit Movie Star,” Lola Ray speak eloquently for the young girls and hopeless boys wading through towering piles of unsolicited angst. MIKAEL WOOD

DOCTOR ALIMANTADO

Born for a Purpose

(Greensleeves)

One of the greatest reggae songs ever recorded, “Born for a Purpose,” could have been written for a mugger or a boss. “If you feel like you have no reason for living,” it began, “don’t determine my life.” In fact, Doctor Alimantado was singing to the driver whose bus hit him on Kingston’s Orange Street in 1976—back when wearing dreadlocks in public could get you run over. But the simple power of the chorus, with its slow “House of the Rising Sun” progression, was so universal that Johnny Rotten later claimed it saved his life, and the Clash name-dropped “the Doctor who’s born for a purpose” on London Calling. The 1977 singles anthology named for Alimantado’s song, and bookended by versions of it, became my New Orleans soundtrack in 1995, the year I confronted both a mugger and a boss. “I am here for a purpose,” sang the recuperating Rasta. And so, I decided, was I. Long out of print and now reissued on Greensleeves, this is the reggae album to confound your expectations of a “reggae album.” Unlike Alimantado’s other classic ’70s compilation, Best Dressed Chicken in Town (which showed him cheerfully shirtless on the sleeve, in shorts with a broken zipper), it wildly leapfrogs studios (pristine Channel One, insular King Tubby’s, shacklike Black Ark) and styles (lovers’ rock, talk-over, dub). Its uniqueness comes not so much from Alimantado’s equal skills as crooner and DJ (what Jamaicans call a rapper) but from his habit of being both at once, and blurring the mixture in dub. He disappeared into obscurity in the ’80s after Born. Maybe his purpose all along was to leave us with this album. PETER S. SCHOLTES