It’s a strange time for museums. Attendance is down across the globe. Blockbuster shows and mainstay exhibits aren’t drawing crowds like they used to. Yet museums are aggressively expanding at a furious pace. New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Minneapolis’ Walker Art Center, and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts are adding substantial additions. The Denver Art Museum has hired Daniel Liebeskind to build a massive steel spaceship of an expansion. And though the Whitney in New York recently ditched plans to pay Rem Koolhaas $200 million for its expansion, the museum is going forward with a more modest alternative.

Not to be outdone, the Seattle Art Museum has caught expansion fever. A lot of hoopla has attached to the Olympic Sculpture Park taking shape near the waterfront. And rightly so—it’s a breath of fresh air in a downtown starved for public parks. But the new downtown expansion, which was unveiled last year and will start to emerge this fall from the giant hole north of SAM, has received little fanfare.

Sure, there’s been dutiful media coverage announcing Brad Cloepfil’s design for the 12-story addition. And architecture critics have been mincingly supportive of the modernist structure, with its focus on views and seamless connection to the galleries in the current 1991 Robert Venturi museum. And yes, Washington Mutual has done SAM a huge favor by trading amortized leases and other freebies in return for a sweet deal on SAM’s prime real estate.

But there’s been little public enthusiasm for the next major civic building downtown after Koolhaas’ splashy Central Library. And that’s because the museum expansion is a functional, frugal, and profoundly uninspiring building. Simply put, this is a warehouse for art and visitors. It’s not going to cause architecture critics to gush like they did over Koolhaas’ fascinating but difficult-to-navigate library.

I’d love to see a show-stopping, signature museum that would finally live up to the promise that the underfunded Venturi design never quite met. But the museum’s plan for expansion, as boring as it might seem, is probably a smart move. “Our space needs are urgent,” says SAM’s executive director, Mimi Gates. “In order to bring great art to Seattle, we determined in the 1999 master plan that we’d need 300,000 square feet of exhibition space in the next 20 years.”

And the arrangement with WaMu has the added benefit of gradual growth. The first phase will open in 2007, providing 95,000 square feet of additional gallery space. Eight unused floors of the museum will be leased by WaMu as office space until SAM eventually moves in. “My colleagues are very envious of our agreement with Washington Mutual,” says Gates.

Despite WaMu’s involvement, the addition is not cheap: $86 million is the current price tag. The museum has embarked on a capital campaign to raise $180 million for the expansion, the sculpture park, renovations to the Seattle Asian Art Museum, and a $10 million endowment to cover increases in staff and overhead. The campaign has raised $113 million thus far.

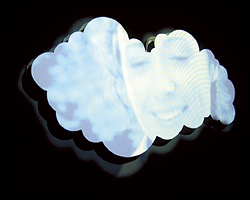

And Cloepfil’s design, as dull as it seems on the exterior, has a cleverly designed series of four light-filled, interlocking shells within its interior. So maybe it’s not so boring after all: a Miesian box meant to showcase a heck of a lot more art, with or without the adulation of architecture critics.

All of this is even more sensible when you consider a stark fact: Attendance at SAM has been declining in fits and starts since 2000. According to recently released figures, in the 2004 fiscal year (which ran from June 30 of the previous year to July 1 of this year) SAM brought in just 337,000 visitors. That’s the lowest annual attendance figure since 1999. Attendance took a jump in 2000 with a successful impressionism show that boosted numbers to 647,000. And 2003 broke the half-million mark. But other years haven’t kept that same pace.

And those 2004 attendance figures are especially troubling when you consider that this summer’s “Van Gogh to Mondrian” exhibit was supposed to be a crowd-pleaser. The museum will probably meet its attendance goals for that show, but just barely.

Which points out a strange dynamic: The museum is succeeding in raising funds from wealthy donors and foundations for its capital projects, but it’s finding it hard to attract the ticket-buying public. Who knows what’s going on— perhaps it’s indicative of the widening gap between the rich and the middle class. Maybe it’s declining tourism. Or art lovers dying off and being replaced by clubgoers.

To counter those declines, SAM has embraced the Wal-Mart approach: bigger box, more selections. But in addition to cold economics, the project helps the museum’s primary mission: displaying visual arts to the community. And heck, if you’ve got the capital, tripling SAM’s public space is going to be a good thing for art in this city.

Let’s just hope somebody shows up to see it all.

Andrew Engelson’s Fall Favorites

Transcendental landscapes

It might be a stretch to say that the Hudson River School—Thomas Cole, Frederic Church, and Alfred Bierstadt among them—invented the American wilderness. But what these early-19th-century painters did accomplish was to translate European notions of landscape and romanticism and fit them to the vast spaces of the North American continent. Influenced by Thoreau and Emerson, these New York painters shifted the popular view of nature from something to be feared and fought to something sublime and worthy of reverence. This collection of 50 important landscapes from Connecticut’s Wadsworth Antheneum features work by Cole, Church, Bierstadt, and several others. Opens Oct. 2. Tacoma Art Museum, 253-272-4258.

Celebrity skin

SOIL, the cutting-edge, artist-owned gallery formerly on Capitol Hill, becomes the latest venue to migrate to the new Tashiro Kaplan building near Pioneer Square. After a group show to mark SOIL’s opening, October brings a solo show, “Fame,” by Seattle artist Samantha Scherer. Scherer’s pen-and-watercolor paintings of celebrity body parts are very funny—in the past she’s done portraits of Tony Curtis’ belly and Condoleezza Rice’s scowl. As hilarious as Brad Pitt’s nipple might be, Scherer’s art actually delves into all sorts of deeper issues: How does the brain recognize faces? Why do we have a fetish for celebrity? And what exactly are Angelina Jolie’s lips made of? Opens Oct. 2. SOIL, 206-264-8061.

Evocations of empire

Spain in the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries was the world’s superpower, dominating the seas and never bothering with a silly “coalition of the willing.” One of the spoils of global empire and wealth was a flowering of science and art. Spain in the Age of Exploration is more than an art exhibit—this sizable collection will survey Spain’s 300-year golden age. It’s packed with scientific instruments (illustrating the Arab influence on Spanish culture), suits of armor, books, and other trappings of empire. But it’s the art that will draw most of us—and there should be a decent selection of work on view from Velázquez, Murillo, and Zurburán and one minor piece by Francisco de Goya. Opens Oct. 16. Seattle Art Museum, 206-654-3100.

Snow show

Saskatchewan-born artist Tania Kitchell has a very deep relationship with snow (considering the winters she must have grown up with, I guess she’d have to). Her understated photographs document one woman’s interaction with weather and environment—fleeting, staged, and open to the chaos of the outside world. In the past, she’s done things like hug large snowballs or record the winter steam of her breath. It sounds trite in the description, but there’s just something very sweet and quiet—like a fragile little Björk ballad—in Kitchell’s images. This is the first solo show by the Toronto-based artist. Opens Dec. 2. James Harris Gallery, 206-903-6220.