Alan Corkery Hahn

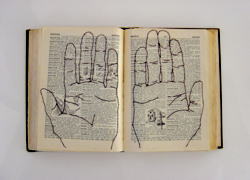

I once came across an arcane old library book, 19th-century journalist Edmund Lepelletier’s highly inaccurate biography of poet Paul Verlaine, to which a previous reader had added heated commentary in the margins. To my surprise, I agreed with my predecessor’s amusing fury—and the normally solitary experience of reading became an activity shared with an anonymous friend. This is the sort of interaction local artist Alan Corkery Hahn, 37, explores in his own book-defacing/enhancing (depending on how you look at it) art. Using thread given him by a stranger on a train from Venice, Hahn carefully hand sews cursive words and images directly onto the pages of old texts. As with that annotated Verlaine bio, Hahn’s playful embellishments forgivably break the taboo of defacing books by being cleverly engaging. After originally investigating bookbinding as a UW art student, says Hahn, “I found that my interest stemmed not from the craft of bookmaking, but from the interaction between the reader and the book, and the evidence of that reaction. . . . I found that the book (an object designed specifically for the hand—to be touched, handled) was a perfect repository for the human touch.” These “modified” books are also quite whimsical. The Thing contains a blade of wheat and the words: “The least/most thing” with “least” and “most” crossed off, diminishing a superlative declaration to a humbler statement. In Dictionary (pictured), two open hands are stitched across two dictionary pages, seemingly holding all the definitions from “morning” to “mouse,” as if vocabulary and knowledge could be cupped like a drink of water. In Wonderland, Hahn has added to a printing of the classic Lewis Carroll story the words “this was my grandmother’s/then it was mine/Now it’s yours.” Here was one instance Hahn hesitated: “(It) was a book handed down to me from my grandmother. It’s apparently a very rare edition of Alice in

Wonderland printed in Gregg’s shorthand. I suspect it was worth more as a collectible book than it is since I made my interventions in its pages. I held onto it for a long time before I finally decided [that] if I really wanted to participate in a dialogue with the book (from the author, to previous owners, to me, to the art viewer), there was no better place than the pages of this heirloom book.” SUE PETERS