Seattle sci-fi insiders call it “Siffumhoff”: Paul Allen’s new Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame. When it opens in June, it will be more commonly known as SFM. Right now it’s under noisy construction in the Blue Potato section of EMP—the space formerly occupied by the Funk Blast ride at Experience Music Project. “All of these cases are just gonna be filled!” exults the jovially ursine Greg Bear, raising his voice above the shrieking saws and banging hammers inside the Potato. He is SFM’s board chairman, an adviser to Microsoft and the CIA, and a quintuple Nebula-winning author. “E.T. has just arrived. We’re gonna have the Alien Queen [from Aliens], all 18 feet of her, kinda hunkered down.” Since the case is 12 feet high, she’ll be crouched as if to pounce and devour visitors. Expect Harrison Ford’s Blade Runner spinner car, but not Anakin Skywalker’s podracer—it was too big. “Probably the centerpiece is Spacedock—you’re gonna have 25 spaceships from films and books . . . all lined up in glorious 3-D!” Viewers will be able to manipulate the digital models in virtual space, compare them for size, armaments, fuel capacity, top speed. “You’re in the viewport of the space station, and you’ll be watching Rama,” Arthur C. Clarke’s alien spacecraft, “90 kilometers long, the size of an asteroid!”

Bear is enthusing about an imaginary object that weighs 10 trillion tons, but he’s gesticulating mostly at empty space. At this point, about all you can see at SFM are glass cases, construction debris, a wall of glass bricks bearing the likenesses of sci-fi celebs, and oval portals between rooms. The portals are brand new but look scratched, dull, and scuffed. This is intentional and symbolic. “It’s ‘Wreck Tech’ architecture,” explains Bear, “the designer phrase for what you see in the Nostromo [spaceship] in Alien, or in the Millennium Falcon in Star Wars. That, basically, used-spaceship look. It’s been around a while, they haven’t been painted recently.”

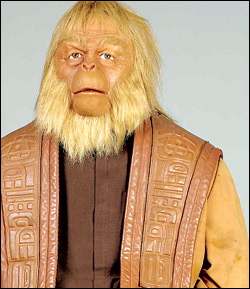

Wreck Tech is the key to the very identity of SFM. Speculative fiction has wised up since the wild-eyed optimism of its visionary early days, and SFM reflects the downbeat sensibility of today. Even though sci-fi fans can hardly wait for the next tech breakthroughs, some of which will be on view in SFM’s “Not So Weird Science” exhibit, they know that the future will be rough and tumble, not happy and shiny. Despite some forward-looking, hopeful exhibits, like “SETI Fiction and Fact,” which will explore the Paul Allen–funded effort to receive communications from actual ETs, SFM will essentially be, like any museum, retrospective. It will celebrate a past when geniuses could envision happier futures and it will chronicle sci-fi’s evolution into negativity, including the bleakness expressed in Planet of the Apes (the costume of Dr. Zaius will be on display). There also will be vistas of cities of tomorrow, as envisioned by The Jetsons, Blade Runner, and The Matrix. What’s fun about The Jetsons is how ridiculously unlikely their leisurely life is; the latter two flicks capture the modern sci-fi mind-set—awed by gizmos and cool ideas, but hip to the grim facts of future life. Today, we dance to a post-apocalypso beat: Tech does not improve human nature.

Thus SFM’s essential thrust is the opposite of the last big science-fiction extravaganza in these parts, the 1962 World’s Fair, which was all about the shiny, perfect techno-future that was supposed to have come true by now. The “World of Tomorrow” exhibit at Seattle’s Century 21 Exposition, writes University of Washington historian John Findlay in his definitive book Magic Lands, “left little room for pessimism. To Americans in 1962, the future promised to be orderly, efficient, and prosperous, as well as humane and enlightened and automated.” The most popular exhibit was the hopeful Hall of Science, which attracted twice as many people as the Space Needle. In the “World of Tomorrow” exhibit, folks got a glimpse of what technology would do: make workers so productive that their bosses would institute a 24-hour work week. News flash from Century 21: Increasing tech efficiency means you’re out of a job or a soul-drained slave to PowerPoint.

Sci-fi writers are no longer starry-eyed dreamers. “There’s a very strong barrenness that permeates recent depictions of the future,” says Jules Verne scholar Judith Adams. “Now technology [is] a killing thing. The way we use technology in our culture is as a way to destroy your peers, so you can be more successful yourself.” Aliens is about capitalists willing to feed humanity to monsters in pursuit of greed; the spaceship Nostromo is named after a Conrad novel about greedy self-destruction.

The most prophetic work of sci-fi turns out not to have been the rosy visions of the World’s Fair but the dark ones of Blade Runner. Now when a citizen gets his hands on some new technology, his first thought is not his thrilling participation with the nation’s future, like a 1962 fairgoer laying hands on John Glenn’s capsule. Today, we presume tech is our enemy. When Bear paused to introduce the journalists touring SFM to its new director, Donna Shirley, the NASA vet who helped put the first robot on Mars, he jestingly claimed she had occult governmental powers. Standing before the 25-spaceship exhibit, Bear said, “Shirley actually knows how to run the controls—just wave your hands like in Minority Report!” “Actually, there’s a kiosk,” said Shirley. “You put your thumb on it, and that’ll admit you to the computer system.” One of the journalists asked, “Is that connected to Homeland Security?” “No!” said Shirley.

SFM sounds like a gas, but it does prove one thing: The future isn’t what it used to be.