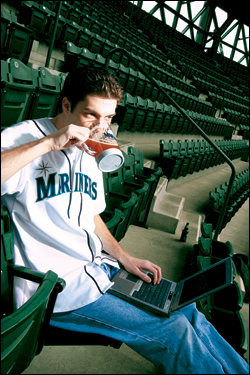

Derek Milhous Zumsteg is a 30-year-old program manager for Expedia.com, an affable Eastside resident with a cheerful affection for all things beer. He’s also one of the smartest baseball thinkers in America—a longtime author and analyst for Baseball Prospectus (www.baseballprospectus.com), the nation’s pre-eminent national-pastime think tank. And he’s also, through a daily Web log named U.S.S. Mariner (ussmariner.blogspot.com), the most prominent face of a growing Puget Sound blogosphere of suffer-no-fools Seattle Mariners analyst-fans, who are trying to reconcile their longtime love for the home team with a reluctant but rationally considered belief that their love won’t be returned in the form of a fluttering pennant. In their view, the 2004 edition of the Mariners, which opens the season against the Anaheim Angels next Tuesday, April 6, will win fewer games than last year—around 85—and will likely stand by a third straight year as their American League West archrivals, the Oakland Athletics, win a playoff spot. Yes, the A’s, with a budget of $43 million, will do better than the Mariners, who have a payroll of more than twice that. “They are always going to be able to find advantages that will beat the Mariners,” says Zumsteg, “because they’ll find them where the Mariners are not looking. Because they have to.” Zumsteg and the others say they can prove it. And they say there’s ample evidence that the Mariners don’t really care to hear about it.

“It is a wonderful thing to know you are right and the rest of the world is wrong.” Bill James wrote those words nearly 20 years ago in one of his groundbreaking series of annual Baseball Abstract books. The founding father of the objective performance analysis movement came to realize that baseball is the one game in which virtually every aspect of performance can be measured and value-weighted through the compilation and analysis of statistics, in much the same way a business can use data about sales and revenue, weigh them against market-force indicators, and make quarterly projections about expected future performance. He found that the statistics can be used to predict, with reasonable accuracy, what teams will win and which players will be effective. James also found, to his surprise, that the people who ran Major League Baseball organizations didn’t much give a shit.

Professional baseball is also unique in having and perpetuating a sepia-toned mystique that serves as a wall between those who have managed, played, and scouted the game and those who couldn’t hit a Pony League curveball. The insiders of this brandy-and-cigars social club, as Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game author Michael Lewis recently painted it in Sports Illustrated, are deemed to have special seat-of-the-pants wisdom about what makes good teams, good ballplayers, and good game strategy—a belief often enthusiastically reinforced by their gatekeeper friends in the mainstream media—that the rest of us simply can’t understand. As many a poet and pundit, from Walt Whitman to George Will, has rhapsodized over more than a century, greatness in baseball is measured not in spreadsheets but in the shape of a player’s body; not in statistics but in the sweetness of his swing; not in his platoon-split and park-effects assessments but in his proven character, experience, and leadership. Thus it was; thus it always shall be.

James drifted from contemporary windmill-tilting to writing about baseball’s past. But thousands have eagerly scrambled to fill his void, to take his theories and theorems forward and refine them until there were no questions about any aspect of a baseball play or a player’s performance that could not be objectively asked and answered. Sabermetrics, as the new-school study of baseball is called, is the namesake of the Society of American Baseball Research, which has nearly 8,000 dues-paying, proud-to-be-outsider members. And, quietly, James’ ideas did take root inside some baseball organizations, as the sport’s polarizing economy of scale forced smaller-market teams and others that are not the New York Yankees to adopt more aggressive business models, not only to survive but to stay competitive. The evolution of one such successful program, those hated Oakland A’s, was skillfully chronicled in Lewis’ controversial 2003 best seller, Moneyball. And James received the ultimate testament to his work when another adherent of his beliefs, the Boston Red Sox, hired him in 2002 as a senior adviser.

Sabermetric regimes are now in place in four major-league cities—Toronto and Los Angeles are the others—and even as other organization leaders sniff at A’s General Manager Billy Beane, the hero in Moneyball, and his perceived bragging about how he fleeced teams with bigger budgets in trade after trade (no less than semiretired Mariners General Manager Pat Gillick dismissed the book in a Seattle Times interview as being “in poor taste”), they are hiring statheads and showing other signs of quietly implementing distinctly Jamesian techniques.

But not in Seattle. And from the perspective of the Mariners, why should they? The “old-school” way, it can be argued, has done quite well for Seattle. The M’s won 93 games last year, and 93 the year before that, and more games—116—than any team in American League history the year before that. They have overflowing streams of revenue from everything from overpriced tickets to television and radio broadcast contracts. They have fanatically loyal fans, from Anchorage to Ashland, superior regional and Pacific Rim marketing, a well-stocked farm system, and the best international scouting organization in the solar system. And a gorgeous cathedral of a home in Safeco Field. Nobody is going to tell the Mariner front office what it has to do to win. Tell 66-year-old general-manager-turned- consultant Pat Gillick, who won a World Series title with the Toronto Blue Jays in 1993, that there’s a new way to build on his success? No way. Or tell new General Manager Bill Bavasi, old-school-baseball-family scion credited by some as the architect of the 2002 World Champion Angels, that computer geeks have come up with an approach that might make his beloved old-school scouts and development people less influential? Not bloody likely.

This not-at-all-evil empire is led by a stable and active ownership; its chairman and chief public face is former Nintendo of America Chief Executive Howard Lincoln. A good company man. The ultimate company man. If the characterization in Seattle Post-Intelligencer columnist Art Thiel’s recent book, Out of Left Field, is a reliable indicator, Lincoln is fiercely committed to surrounding himself with good company men inside the dugout and out, in pursuit of what the most recent off-season moves and Lincoln’s newspaper interviews have clearly established as a three-pronged goal: Make money. Hire people of good character with proven records of success on and off the field. And provide a fan-friendly, market-competitive product.

That’s precisely the root of the Mariners’ problem, Zumsteg says. He has no problem with making money, but he and fellow bloggers at U.S.S. Mariner—Grand Salami writer Jason Barker and amateur minor-league analyst David Cameron—say they can show that a bewildering series of personnel shuffling this off-season has shown something less than fiscal prudence. The Mariners love to point out that since the dawn of the new millennium, they’ve won 393 games to the A’s 392. But Oakland got those wins spending just $156 million, while Seattle invested $301 million in payroll over those same four years. And, to Zumsteg, “competitive” is a sneaky word. As any job seeker contemplating “competitive salary and benefits” knows, “competitive” is code for “as lame as everybody else’s.” And, in Zumsteg’s empirically established view, the Mariner idea of “competitive” is code for “at least as lame as we were before.” As he puts it: “They want to be competitive more than they want to win.”

Bill James, the founder of objective performance analysis in baseball, now works for the Boston Red Sox.

(Bizuayehu Tesfaye, Associated Press) |

This isn’t the usual reactionary sports-talk-radio blather. The rationale behind the statement is not emotional— the facts are there for anybody who cares to analyze them. Here’s how it works: Let’s say you want to know whether Raul Ibanez is likely to help or hurt the Mariners in 2004. The 32-year-old, who hit .294 with 18 home runs and 90 runs batted in for the Kansas City Royals in 2003, signed a three-year, $13.2 million deal last fall to be the team’s starting left fielder this season. You might say, as Bavasi did recently in an interview on the Baseball Prospectus Web site, that “we didn’t think there were any players out there that had the potential to provide production that he did for the deal we did. We felt he could do a good job of making contact and pulling the ball in Safeco.” Or you might start with the fact that the two most important offensive skills in baseball are the ability to get on base and advance base runners. How well does Ibanez do those things? While his “triple crown” stats for batting average, home runs, and RBI look good and have popular resonance, they don’t really measure his ability to produce offensively. Instead, take his numbers—triple crown, as well as walks and strikeouts (frequency and ratio, as well as totals)—measure them against those of other American League left fielders, average them, and weigh Ibanez against the average. Turns out he’s pretty excruciatingly average. Then, adjust his numbers for “park effects.” In averaging and isolating other readily available team-by-team and leaguewide data, it’s clear that hitters register much better numbers in Kansas City’s cozy Kauffman Stadium than in comparatively cavernous Safeco Field. A “park factor” formula developed from crunching those numbers shows that the disparity between hitting in Kansas City and in Seattle necessitates that Ibanez’s numbers take about a 15 percent discount at the Safeco Field door. Factor in what the average-and-isolate

statistical method has proven through history—that ballplayers develop toward a peak-performance period between the ages of 27 and 30 (aside from the occasional freak of nature, statistically speaking, like Edgar Martinez or Jamie Moyer). Add the fact that the players throughout history with statistics most comparable to Ibanez all entered periods of distinct performance decline in their early 30s. Those figures together can be distilled into a future-projection formula (Baseball Prospectus’ PECOTA system has proven the most accurate of about a half-dozen formulas out there) showing that Ibanez can be expected to hit about .264 with 15 home runs this season, less than that in 2005, and enough less in 2006 that he’ll be a $4.3 million budget blunderbuss. Bavasi has countered this by trotting out a little statistical analysis of his own: the fact that Ibanez hit .381 in 42 at-bats as a visitor to Seattle in the past three seasons—a statement that should have any statistical analyst worth his or her salt screaming, “Insignificant sample size!”

Then place that projection in a team context. At the time, the Ibanez deal not only gave the Mariners four starting outfielders—Ibanez, Randy Winn, Mike Cameron, and Ichiro Suzuki—but it blocked the path of advancement for the team’s top minor-league outfield prospect, awesome Aussie Chris Snelling. The method behind the Ibanez madness became more clear when the Mariners, unable to reach a deal with the perennial Gold Glove–winning Cameron, didn’t offer last year’s center fielder arbitration and let him leave as a free agent, subsequently shifting the decent but unspectacular Winn to center field. Zumsteg, working with more comparative and sophisticated metrics devised by Baseball Prospectus, looked at both offense and defense and calculated that the shift from a Winn-Cameron outfield duo to an Ibanez-Winn one would cost Seattle about 30 runs—weighted by the latest formulas as a net loss of about three games.

Seattle Mariners General Manager Bill Bavasi: “in favor of subjective projection.”

(John Froschauer / Associated Press) |

Add in the deal’s financial context. The Ibanez deal was a head-scratcher because it was the first major free-agent signing of the 2003–04 off-season, made before the value of the market was known. As it turned out, Ibanez’s signing was anomalous. Smarter teams waited for the market to calibrate itself before signing similar players to smarter deals. For example, former Mariner José Cruz Jr., two years younger, hit for more power and posted a far higher on-base percentage than Ibanez. The Tampa Bay Devil Rays— supposedly baseball’s most inept organization—signed Cruz for two years and $6 million. Were there other, less expensive options available of comparable quality? Look no farther than Snelling, who, despite his spate of injuries, still “projects” by any metric formula as a future star. The 22-year-old’s predicted 2004 stat line: .263, with Ibanez-esque midrange power. His price tag: the major-league minimum of $300,000. None of that seems to have occurred to the Mariners, who, at the time of his signing, prattled in the press about Ibanez as a “proven veteran” and “clubhouse leader” with “good character.” Says Zumsteg: “The Mariners paid an extra $2 million to $3 million a year for his ‘clubhouse presence’ and his ‘leadership.’ And that’s money they might as well have rolled up and smoked.”

All of this is demonstrable for anybody who cares to have it demonstrated to them—or work it out for themselves. (Do it yourself by getting the stats from www.baseballreference.com and the formulas and other data from www.baseballprospectus.com.) It’s also readily demonstrable that the Ibanez deal was hardly anomalous for the Mariners. Virtually every deal they made during the off-season, be it a trade or free-agent signing, blocked or dispatched a player with rising or stabilized value in favor of a more expensive player who demonstrated success in the past but doesn’t project well in 2004 or beyond. World Series star infielders Rich Aurilia and Scott Spiezio, two declining years removed from their shining moment on the national stage, replaced Carlos Guillen and blocked Double-A minor-league stud Justin Leone. Cringe-worthy third baseman Jeff Cirillo was shipped to San Diego for three near-worthless players—one of whom, pitcher Kevin Jarvis, has a $4.5 million salary that will almost certainly have to be swallowed by Seattle by the end of spring training. First baseman Greg Colbrunn, an ideal right-handed complement to lefty John Olerud, was flipped back to the Arizona Diamondbacks for fourth outfielder Quinton McCracken, who projects to be no better a player than loyal organizational soldier Jamal Strong, a well-developed reserve outfielder who has nothing left to prove—and will continue proving it this year at Triple-A Tacoma. The signing of former Mariner pitcher Ron Villone to guaranteed money, as well as the nonroster spring-training invitations to washed-up veteran pitchers Mike Myers and Terry Mulholland, posed a solid barrier against interesting organizational prospects like George Sherrill, Bobby Madritsch, and Matt Thornton. And so on and so on, from a wretched bench to pitchers who will suddenly seem more ineffective because the

defense behind them is not as capable of protecting them as last year’s. (Look for pitchers who put a higher-than- average percentage of balls in play, such as Ryan Franklin and Shigetoshi Hasegawa, to suffer elephantiasis of the earned-run average this season.) The Mariners, despite whatever politically expedient noises they’ve made in the press about their desire to field a championship-quality team, have chosen “proven,” past-their-prime players over less- expensive rising prospects at every turn.

It’s the ultimate old-school strategy, one that’s been tried and failed multiple times in the Mariner past. (Anybody remember how well Willie Horton, Richie Zisk, Gorman Thomas, Milt Wilcox, Glenn Wilson, Jeffrey Leonard, Pete O’Brien, Kevin Mitchell, Tim Leary, Felix Fermin, Heathcliff Slocumb, and Rickey Henderson worked out?) It says that objective analysis is not as important as subjective wisdom. The difference is that one can be proved; the other has to be taken on faith. Bavasi, when pressed on such subjects in interviews, says only, vaguely, that when push comes to shove—particularly when looking at farm talent—”you have to adjust the impact stats have in favor of subjective projection.” Zumsteg tries to fathom such regressive flat-earth stubbornness: “For a long time, doctors believed that the way to cure patients of illness was to remove humours from them, by bleeding or draining bile, and so forth. Among them, there were renowned surgeons and doctors. Would anyone want their spouse, or kid, treated by one of those surgeons today? Or would they want a modern doctor, armed with instruments and vast amounts of medical research, able to take X-rays and take MRIs, send out for lab work, and so forth?” Even Bavasi admits the Mariners have no governing organizational plan. As he told Baseball Prospectus: “Anybody that goes into any situation adhering to specific philosophies has a good chance to get burned.”

And Zumsteg’s contemporaries are only too unhappy to stoke the flames. “Is it pessimism to point out that the emperor has no clothes?” asks Peter White, a 25-year-old online editor who maintains his Mariner Musings site (www.all-baseball.com/marinermusings) from the Washington, D.C., area. “It doesn’t take a conspiracy theorist to surmise that the Mariners are more concerned with providing a profitable, family-friendly entertainment venue to the good people of Seattle rather than collecting flags to hang in the ballpark.”

Raul Ibanez: Was acquiring him smarter than promoting minor-leaguer Chris Snelling?

(SEATTLE MARINERS) |

Stephen Nelson, a 52-year-old self-employed environmental consultant who runs the Mariners Wheelhouse site (www.noslenblog.blogspot.com), posits the problem of the Oakland-Seattle rivalry in terms the business-minded Mariners might appreciate: “Suppose this were the real world, and a business one day discovered that one of its competitors had figured out how to provide an equivalent product or service for half the cost. That business would turn itself inside out remaking itself to meet the competitive threat. Company culture would never stand in the way of change, because it would be a survival issue. Baseball clubs, though, are monopolies in their operating areas. The various teams compete on the field, but not financially. The fact that the A’s are outperforming the Mariners on one-half the cost does not cause revenues to flow from the Mariners to the A’s. So the competition function that would ordinarily cause organizations to adapt is not present.”

And forced adaptation to the new school of baseball thinking, or, at least, integrating it into an old-school foundation, Zumsteg believes, is the Mariners’ only chance. Despite his fervent fandom—”Nobody loves the game more than those who want to understand it,” he says—Zumsteg thinks it would “almost” be bad for Seattle if the team were to win the pennant with the club’s current composition, under current operating culture. “I have to admit that I’m often torn,” Zumsteg says, “in that I love the Mariners and cheer for them as much as anybody, but I get so frustrated at times with what they do and why they do it that I want them to fail, and fail badly, so that they finally realize that there’s a better way.” If they continue to be moderately successful, he predicts that “in three years, they’ll be playing .400 ball, will be losing money, and won’t know what hit them: ‘We have such a great bunch of veteran guys! How could this happen?'” What won’t happen, the bloggers believe, is the dawning of enlightenment— at least not as long as Lincoln is running the show. Because the Howard Lincoln painted in Out of Left Field knows everything he needs to know already about how to successfully run a business—Hello! Nintendo!—so why does he need new knowledge? And that, the bloggers believe, will continue to be the Mariner stumbling block. As no less than Bill James put it last year to Slate: “There will always be people who are ahead of the curve and people who are behind the curve. But it is knowledge that moves the curve.”