From a humble, one-room schoolhouse in Lilliwaup, Wash., on Hood Canal, Mike McGrady attained the very pinnacle of the writing profession by aiming for the pits, giggling all the way. Today, he’s a retired newsman living in his hometown, who just finished a book about an actual opera singer turned double agent during the Cold War. But McGrady’s real fame came from a book that was fiction with a vengeance. In 1966, appalled by the best sellers of Jacqueline Susann and others, he challenged his colleagues at Newsday, where he was a distinguished editor and writer, to perpetrate a book so mindlessly crass it could not fail. “There will be an unremitting emphasis on sex,” he warned. “Also, true excellence in writing will be quickly blue-penciled into oblivion.”

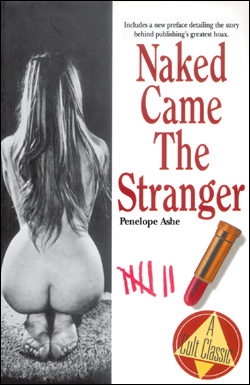

Though his Newsday publisher, Bill Moyers, refused to write a roman-à- clef chapter about his sexy ex-boss, Lyndon Johnson (who once boasted, “Ah had more women by accident than JFK had on purpose!”), two dozen Newsday men and women rose (or sank) to the occasion. Using the pseudonym Penelope Ashe, an imaginary “demure Long Island housewife,” they cranked out a chapter apiece of what became Naked Came the Stranger, a fiction rife with ice cubes applied to prostates and couples flagrante delicto at the Throgs Neck Bridge tollbooth.

Published in 1969, the book was a sensation, selling an estimated several million copies. (Gonzo publisher Lyle Stuart is an eccentric who refuses to divulge sales figures.) This January, the book was reissued in paper (Barricade Books, $12), offering new readers a chance to acquaint themselves with its satiric smut. Stuart—the publisher of the original and the reissue— remains coy about its dollar gross: Up to $1.2 million (in today’s dollars) was subsequently split 25 ways. The contributors missed out on the bigger money in film and paperback revenues. “We signed the worst contract in world history,” says McGrady. Still, the wage wasn’t bad. “If you did one hour’s work, it was very good pay.”

More important, they made shit-lit history. “It was on The New York Times best-seller list for 25 weeks or so,” says Stuart. “[It] probably got as much publicity as any book I ever knew.” Partly, it was the sex: Few books had any back then, and America’s airwaves were yet to inundate the citizenry with images of nipples and naughty talk. In 1969, everybody was suddenly starting to have sex like crazy, and the news was bound to escape into print any minute.

Naked happened at the right minute. Though the book’s sexual adventures were invented, Billie Cook, the sexy young Jacqueline Susann look-alike hired to pretend to be author Ashe, said its faux revelations sounded much like what she’d heard when she worked for a maid service. The book’s sales were partly the result of the same sort of lascivious curiosity that made The Nanny Diaries hot more recently. Naked wasn’t so much erotic as deliciously indiscreet.

Then, the paperback sales (and revenues) swelled even higher when glamorous Ashe was exposed as a hoax by a couple dozen grubby newshounds. The news media went berserk. McGrady juggled his fellow journalists more vigorously and skillfully than the book’s heroine did her numerous boxer, doctor, gangster, and rabbi inamoratas. “He kept promising everybody an exclusive,” cackles Stuart. “Newspapers were calling from all over the world. Walter Cronkite flew out in a helicopter to do interviews. You couldn’t spin the dial without seeing or hearing one of the 25 authors.”

The timing was right for a more melancholy reason, too. “It was the tenor of the times,” says McGrady. “Vietnam was being drummed into us every day.”

Everybody went on to greater things than Naked—not that anything wouldn’t constitute a step up. Contributor George Vecsey wrote Coal Miner’s Daughter and 18 other books, then became a top New York Times sports reporter. “He wrote my favorite chapter, because it was fairly clean—the one chapter I didn’t have to apologize to my mother about,” recalls McGrady. Despite his unsullied pen, Bill Moyers lost his Newsday job in large measure because of the Naked hoax. “I wrote Bill a note saying, ‘Gee, I’m really sorry to have been responsible for your leaving Newsday, but it’s the best thing that ever happened to you, because you got into television!’ It made his life.”

McGrady went on to write A Dove in Vietnam, a book serialized in The Seattle Times and many other papers, which sold “like, 23 copies.” He later penned two books about Linda Lovelace, the porn actress whose Deep Throat could be seen as a successor to Naked in the nation’s cultural/sexual history. These books told of the monstrous ordeal Lovelace endured on the dark side of the sexual revolution he had earlier lampooned.

McGrady’s favorite of his own books, though, is the out-of-print 1970 Stranger Than Naked, or How to Write Dirty Books for Fun & Profit. It’s the story of the making of the Penelope Ashe book and a much better read than Penelope’s. It’s also been optioned by Working Title, the British outfit behind comic adaptations including About a Boy and Bridget Jones’s Diary.

It’s ironic that such a notorious publishing hoax should be affectionately reissued at a time when journalism is consumed with self-recrimination over the exploits of Jayson Blair, Stephen Glass, and Jack Kelley. Yet Naked was confabulated in a spirit much different from today’s hoax- artists: Those ’60s pranksters were not looking to advance their own careers by duping their editors with too-good-to-be-true copy; they were simply trying to spoof the world of crap novels by out-crapping them—and they succeeded beyond their wildest dreams.

McGrady doubts a book like Naked would ever create such a sensation today. “People [then] knew they could go out and buy something that was sorta forbidden fruit. Now what’s forbidden?” We lack the sexual ignorance that made the Naked authors’ fantasies so delightfully absurd. Every college-newspaper sex columnist knows more about erotica than married reporters did in 1969. Carl Hiaasen, Dave Barry, Elmore Leonard, and company tried to reprise the satiric orgy in 1996’s Naked Came the Manatee, but it sank like a stone off the coast of South Florida. Reading Naked today, we can all sensuously drift back to a time when concupiscence was still big news, boozing reporters ran the newsroom, and a nonexistent yet demure Long Island housewife stepped out of her housedress and flashed a more innocent America.