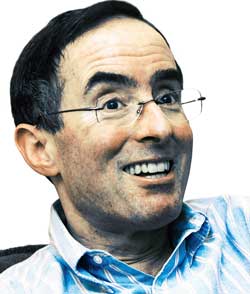

MICHAEL KINSLEY is sitting on a couch in his Madison Valley house, discussing the experimentation that has marked his Internet brainchild, Slate magazine. “I really want you to see this,” effuses the normally calm, reasoned Kinsley. He jumps out of his seat, runs upstairs, and brings down a Tablet PC, Microsoft’s wireless, state-of-the-art laptop. He wants to show me how you can print out the Internet publication as if it were a weekly magazine, incorporating everything posted on the site over seven days’ time. What’s more, you can choose from an array of formats, including ones that divide text into columns, just like a conventional print publication. He fiddles for a while with the Tablet, unable to bring up the option he wants. “Come on, I got a reporter here!”

Finally, he gives up and takes me up two flights of stairs to his book-lined office, where his desktop computer sits. After a series of clicks, the text arranges itself in proper column format. Then, he notices a function that says, “It speaks.” He clicks on it. An automated voice begins slowly reading the text. “I mean, I didn’t even know that!” Kinsley says.

This is the man who knew nothing about the Internet before he hit the Northwest seven and a half years ago? The highbred, intellectual, and slightly nerdy creature of the East Coast media establishment? Kinsley has changed. Thrust into the technology-obsessed culture of Microsoft, under whose auspices Slate has operated, Kinsley has turned into what Josh Daniel, a former editor at the magazine, calls “a gadget geek.” Now a communications manager for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Daniel recalls going into the magazine’s offices many a morning to find that Kinsley had been up late into the night “playing with some Excel spreadsheet that he wanted to do something really cool with on Slate.”

The effort has paid off. Slate is a rare publication in the online world: It is alive. Remember Suck? Feed? The Industry Standard? For all the predictions that Internet journalism would supersede traditional media, it is the Web that offers a storied tale in media casualties. For the most part, the Internet publications that have made it to the top of the heap are those riding the coattails of mainstream media outlets such as the The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Time magazine. Of course, Redmond-based Slate has been carried comfortably in Microsoft’s incredibly deep pockets, a factor that cannot be overestimated in understanding why Slate has thrived while its peers have died. That does not, however, diminish the publication’s standing as the fourth-most widely read entity on the Web, appearing on the screens of nearly 5 million computers every month, according to Nielsen//NetRatings. Slate‘s archrival, Salon, in comparison, attracts 1.7 million monthly readers (measured by unique computer addresses) to its free content, according to Nielsen, and just 62,000 to content available only to paid subscribers, according to the most recent publicly released data. (It should be noted, though, that Slate attracted less than half as many subscribers as Salon has now during a brief, dismal foray into paid circulation five years ago.)

Slate heads into 2004 poised for growth. It’s got a new broadcast jointly produced with National Public Radio, called Day-to-Day. Featuring snippets from Slate writers, it promises to increase the magazine’s brand recognition beyond the Web.

What’s more, this is a presidential election year. With a heavy political bent, the magazine typically sees its readership increase by half in the months leading up to a Big Kahuna election. The magazine is gearing up. It recently came out with a book, The Slate Field Guide to the Candidates 2004, taken from dispatches on the site. (When Howard Dean says, “I’m here to represent the Democratic wing of the Democratic party,” for example, he really means “any candidate to my right is a sellout.”)

On the Web site, you can read constant campaign updates that drill down into the blow by blow. Why did Al Gore endorse Dean? Slate‘s chief political correspondent William Saletan wanted to know in December. Wasn’t that inconsistent with Gore’s professed desire, post-Florida, to let voters, not politicians, decide elections? In the run-up to the New Hampshire primary, writer Chris Suellentrop entertained farcical reasons for John Kerry’s baffling ascension—”the candidate who uses the most superlatives is now guaranteed victory,” “the candidate who receives the worst introduction speech of the campaign wins”—before concluding, “I’m left with one answer: He’s taller.”

On the Red West Campus of Microsoft, Slate Publisher Cyrus Krohn, left, and Editor Jacob Weisberg. (Adam Weintraub) |

A Must-Read for Some

That’s Slate all over: analytical, running through the A, B, and C of possible explanations, reflecting the Harvard law student that Kinsley once was—but also funny. “It’s got whimsy, which is very hard to get in prose,” says Paul Glastris, editor of the small but esteemed political magazine Washington Monthly, where many of Slate‘s writers got their start. When The Atlantic writer William Langewiesche came out with his much anticipated, three-part series on the aftermath of 9/11 at the World Trade Center, a feature on Slate let you click to hear him pronounce his name—a wink at the verbal convolutions happening at select dinner parties across the country.

Slate is sophisticated fare for people in the know. “We’re not a primary news site,” says Jacob Weisberg, who succeeded Kinsley as editor two years ago. “Slate is not a place to go to find out what’s happening. It’s a place to go when you already know what’s happening.” Preferably, one might add, what’s happening in New York and Washington, D.C.—clearly the places that matter for Slate no matter where its headquarters is. What Slate gives you is an original take—usually contrarian—delivered with style, intellectual vigor, and, critical for its medium, timeliness.

It has proved to be a winning combination. On the buzz-obsessed East Coast, there is a sense among the media elite that this oddball national publication, on the Web and from the Northwest, has arrived. “Everyone I know reads it,” says Washington Monthly‘s Glastris. Timothy Noah, author of Slate‘s news-breaking Chatterbox column; well-known political blogger Mickey Kaus; editor-turned-muscular-press-critic Jack Shafer—all are widely read Slatesters in the nation’s capital, according to Glastris. His colleague at the Monthly, founding editor Charles Peters, recalls that the other day Washington Post media critic Howard Kurtz was razzing Kaus for declaring that Kerry didn’t have a chance. “At least Howie had read the stuff,” Peters says.

It makes sense that this crowd reads Slate. Politically, the magazine is slanted left but open to the right in precisely a Washington Monthly or New Republic kind of way. But for that reason, too, it doesn’t turn off conservative readers. Tucker Carlson, the conservative co-host of CNN’s Crossfire (Kinsley, incidentally, used to occupy the liberal chair on the show), proclaims Slate‘s campaign pieces “awesome”—both useful and smart. “They do what The New Republic does,” he says, “except they do it every day.” Carlson has written for Slate, as have fellow high-profile conservatives David Brooks and Andrew Sullivan.

While the political junkies are reading Slate, what’s more striking to New York Observer media critic Sridhar Pappu is that he increasingly hears Slate cited by a variety of commentators, even entertainment reporters. Editor Weisberg has stepped up Slate‘s cultural coverage, causing Pappu to quip in a recent article that Slate was becoming “more hip—more like, well . . . Salon.”

It’s an endless comparison: Slate and Salon, the Web’s two pre-eminent magazines. But it’s a telling one. While Slate has been more inventive with the online medium, Salon has been more inventive with subject matter. The San Francisco– based magazine has reached beyond the usual “important” subjects to write about everything from sex to motherhood to pop icons—often in a personal, emotionally revealing way. Slate has focused on subjects that excite the chattering classes—written in a personal way but rarely in a revealing one. While Slate expertly dissects the world, Salon, more often, goes out to report on it. (Full disclosure: I’ve written for Salon.)

Membership Cards

Whatever their respective strengths and weaknesses, it is Slate, not Salon, that is winning the Darwinian battle of Internet publishing. Not only are its readership numbers far bigger, the magazine is finally approaching profitability, while Salon has long been in deep financial trouble.

At the same time, Slate sees itself as comparable not so much with Salon or other Web publications as with such prestigious print titles as The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and Harper’s. “We’re a member of the club,” says Kinsley, who has continued to write for Slate after stepping down as editor. “What kind of member, you could argue about. Junior member, you might say. An affiliate member because we’re on the Internet? I don’t think so, but maybe. But whatever, we are certainly the only Web site that is a member.” While you might argue about whether Salon belongs as well, Slate‘s club status doesn’t come as a surprise, given that most of its staffers came to the magazine with a membership card in hand. “It’s easier to think of who isn’t from The New Republic,” says Slate‘s Noah, mentioning what was once the “It” magazine for Beltway types. Harvard University and Washington Monthly also show up with striking regularity on staffers’ résumés.

In the ruthless game of who really matters, though, there’s always someone who thinks you don’t make the cut. “They don’t exist in New York,” media critic Michael Wolff of New York magazine declares flatly of Slate. “It’s a very rarefied piece of media. In some sense, it’s media for media.” It’s a harsh comment, and Wolff has reason to dislike Slate given its scathing review of his book, Burn Rate: How I Survived the Gold Rush Years of the Internet. But Wolff gets at the insiderish quality of Slate.

In Wolff’s view, people look at the magazine because they know somebody who writes for Slate, or because they’re interested in hiring somebody who writes for Slate. He allows that Slate has developed as a blue-chip talent pool, most noticeably for The New York Times. The Gray Lady has hired such former Slatesters as op-ed columnist Paul Krugman, TV critic Virginia Heffernan, “ethicist” Randy Cohen, and editor Jodi Kantor, who was all of 27 when the Times handed her the reins of its Sunday Arts and Leisure section. Nevertheless, Wolff says, “Just because you hire from there doesn’t mean you read the damn thing.”

What, then, about Slate‘s 5 million computer screens per month? It’s an impressive number. The New Yorker, the pinnacle of literary journalism for almost a century, has not quite a million print subscribers. The New York Times, arguably the best newspaper in the world, has a Sunday circulation of 1.7 million. If Slate‘s numbers look too good to be true, Wolff contends that they are. When looking at Web readership, he divides by a full 100 because of what he calls “a whole set of behaviors” in addition to actually reading—inadvertent clicking, for instance, or clicking due to momentary interest.

Even Kinsley concedes that some of those 5 million might be passing through Slate for all of 10 seconds. Many get to Slate without having actively sought it, after clicking on a link from MSN.com or MSNBC.com, Microsoft sites with mass audiences. Slate articles linked on those sites, courtesy of its relationship with the world’s dominant software power, are unquestionably a central reason for the voluminous traffic.

Former Slate freelancer Rob Walker, now with The New York Times Magazine, recalls that when his advertising column was highlighted on MSN, “the volume of e-mail would just explode. It was interesting. You’d get a different kind of reader, maybe more of a drive-by reader. On those days, I’d get a lot of e-mails like, how stupid it was to write about advertising. … It wasn’t really a Slate kind of person.”

What’s a readership number that more accurately reflects Slate‘s loyal following? By Wolff’s measure, only 50,000. By Kinsley’s, somewhere between 500,000 and a million. If the chasm between the two estimates seems deep, it’s a reflection of how much there still is to learn about this frontier medium.

The Kinsley Report

On the day before New Year’s Eve, I go to see Kinsley in the house he shares with his wife, Patty Stonesifer, a former Microsoft executive and co-chair of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It’s a graceful house fronted by a columned porch. The bespectacled Kinsley arrives at the door wearing khakis and a pinstriped shirt and leads me downstairs to a sitting room overlooking a patio and an orderly garden.

Kinsley, 52, gave up Slate‘s editorship in 2002, in part for health reasons. He has Parkinson’s disease. On medication now, he looks more vigorous than he has in a while, neither as wan nor as thin. “I feel fine,” he says, noting that he’ll most likely die of something completely unrelated to Parkinson’s. Though he’s taken himself out of the pressure-cooker role of editor, he’s writing more than ever. He’s emerged as a sharp, if reasoned, critic of the Iraq war, skeptical of the weapons-of-mass-destruction rationale and disturbed by what he called an “eerie nondebate” among the American populace about the merits of war.

We meet just after Kinsley delivered a radio segment about Wal-Mart for Day-to-Day; he has a radio microphone in his upstairs office—”the one piece of gear that impresses people in Seattle,” he says. His take on Wal-Mart was classic contrarian Slate. Dipping into the controversy that followed a Los Angeles Times series on the cost-cutting, low-paying mega- box retailer, Kinsley defended Wal-Mart. “People shop there because they like it,” he tells me. “I like it.” The Harvard-bred, Microsoft-paid journalist then rattles off the Seattle-area Wal-Mart locations, including Rainier Avenue and Lynnwood.

We turn to the subject of Slate‘s early days. His arrival in the Northwest caused gasps in political and literary power centers, which have their own kind of provincialism. Was this influential journalist, once editor of The New Republic and Harper’s, really moving to a place associated with flannel shirts and fish? (Newsweek famously put Kinsley on its cover. He was wearing a yellow rain slicker and holding a giant salmon.) Kinsley, who understood that technology was creating a new power base in the West, recalls that he was out to prove a point. “My goal when I came out here was to show, if possible, that the economy of the Net made this kind of magazine journalism easier to do on a profitable basis.” The Net, he believed, would allow publications to escape burdensome paper, printing, and distribution costs—and thereby also escape the need to rely on the indulgence of some millionaire, like his former boss, Marty Peretz, of The New Republic.

“We’ve done that,” he says, referring to Slate‘s announcement last spring that after seven years it had finally turned a profit in the just-finished fiscal quarter. (Technically, because of accounting rules that pertain to Microsoft, Slate couldn’t actually use the “p” word but spoke of revenues exceeding expenses.) “I think this is a major achievement.”

The magazine got quite a bit of press when it hit this milestone, in media ranging from The New York Times to The Guardian of Britain. Alas, Slate Publisher Cyrus Krohn admits that the profitability did not hold. The magazine went on to have one more profitable quarter before finishing 2003 with two unprofitable ones. Slate is, however, reaping a boom in Internet advertising, and Krohn waxes optimistically that sustained profitability is nigh.

“Oh well, I guess I’ve been living in a dream world,” Kinsley says when I break the news to him. He says he hasn’t seen the latest numbers. “Two quarters is not good enough. We had sort of decided it had to be four contiguous quarters. … But, you know, it’s not bad.” He notes that The New Republic has been going for almost 100 years and remains unprofitable. “The New Yorker loses money every year.”

Still, Slate hasn’t fulfilled its original premise. And, Kinsley concedes, the question remains: Where did that money go? The money, that is, that Slate is not spending on paper, printing, and postage, or for direct-mail marketing or (apart from a brief, unsuccessful attempt to charge readers) subscription services. “It remains a puzzle. I think part of it was that we were like—and we shared this with other Web sites in the ’90s—a magazine that had to invent and make its own paper. You know, we had to do a lot of stuff that you can now go to CompUSA and buy.”

Slate developed its own publishing software, which controls the way readers and editors see and interact with the Web site. “Anything we needed to do in terms of multimedia, we had to design ourselves,” Kinsley says. Comic frustrations resulted. At one point, Kinsley got it into his head that he wanted to have ever-changing theme music whenever a reader opened Slate‘s home page. “We couldn’t do it,” he says. The only method the magazine could devise entailed having the reader click a button that said “hear music.” Slate tried this clumsy method once before ditching it. For the rights to the music that one time, Kinsley says, “we paid some unbelievable sum, like $3,000.”

All this experimentation required people. “We had six developers working for us at one point and desperately needed more,” Kinsley recalls. Luckily, Slate had a first-class talent pool at the ready in Microsoft. It also had the opportunity to root around Microsoft for emerging technologies that would be useful. While Slate has always staunchly denied that Microsoft has had any journalistic influence, it concedes that in terms of technology, there has been a mutually beneficial relationship. While Slate has had first crack at developing products, the magazine has served as a test bed for Microsoft’s publishing and readability tools.

Kinsley became fascinated with the technology in part, he confides, because “it’s sort of fun.” More importantly, though, he acknowledges that the Web carries certain limitations, primary among them the necessity of reading on screen (unless you print). “So to make up for that, you ought to maximize the things you can do that they [the traditional media] can’t.”

Lots of Links

How well has Slate succeeded? To webophiles, the magazine doesn’t seem particularly innovative. “Slate is a traditional magazine that’s on the Web, with very few of the things that are most different about the Web,” says Dan Gillmor, a technology columnist at the San Jose Mercury News who is writing a book about the intersection of technology and journalism. “I don’t think it needs to be that innovative,” he hastens to add, noting that he’s a fan of its high-quality journalism. But for cutting-edge Internet journalism, he looks to sites where the content is “becoming less of a lecture and more of a conversation, where the former ‘audience’ is an integral part of the pieces.” He cites Slashdot.org, the self-proclaimed news site for nerds, written largely by readers. Obviously, that’s not what Slate‘s about, although, as Gillmor approvingly notes, the magazine has a feature called Fraywatch, which is essentially a blog that highlights the best material in Slate‘s reader forum.

Steve Outing, who writes for the Poynter Institute’s blog on online journalism, E-Media Tidbits, recalls one Slate feature that won an award from the Online News Association for creative use of the medium in 2002. Called “The Enron Blame Game,” it displayed a graphic that prompted you to click on any one of the numerous players in the Enron scandal—say, Kenneth Lay—whereby all the people he blamed would be highlighted. Otherwise, though, Outing can’t think of too much else on Slate that is innovative. He sees more creative content on MSNBC.com, which he says is full of such “information graphics,” including ones that use audio narration to explain material. “Even The New York Times is getting into a lot of alternative storytelling” online, Outing says. “You might see an audio-narrated slide show,” with the writer or photographer talking about each picture as it appears. Slate‘s Weisberg proudly notes that the magazine is experimenting with art criticism using slide shows and captions. But when you think about it, there’s no reason why such captions-as-criticism couldn’t work just as well in print as on the Web—assuming you could devote enough expensive paper and ink to do them justice.

Nonetheless, as Online Journalism Review columnist Mark Glaser points out, “Some of the really simple things Slate has done have really paid off.” And it starting doing them, if not first, then at least relatively early in Web culture. For instance, Glaser points to a popular Slate feature called Today’s Papers, which looks across the media landscape to highlight noteworthy stories. In itself, that wouldn’t be so noteworthy; clipping services provided media summaries long before the Web. The crucial thing is that Slate provides links to all those stories, so you can read the referenced article instantly. When Slate started doing this seven years ago, it was revolutionary, not only because of the technology, but because Slate was willing to send people away from its own site. Glaser says, “There have been a lot of arguments at media companies: Do we really want to have links to all these other sites?”

Now, Glaser says, “A lot of other people have copied what they’ve done.” Glaser says he had Today’s Papers in mind when he worked at the now defunct Industry Standard and started its online roundup of technology news, called Media Grok.

Slate uses links exceptionally well in the rest of the magazine, too. While many online publications still add links as afterthoughts, Slate often integrates them in ways that truly deepen a piece. Chatterbox columnist Noah is particularly adept at this. In December, when U.S. Rep. Nick Smith, R-Mich., was busy backpedaling on his claim that he had been offered a bribe to vote for President Bush’s Medicare drug bill, Noah linked to a previous radio interview the congressman had done that clearly affirmed the bribe attempt.

Speaking by phone from his Washington, D.C., home, Noah recalls that he first got excited about links because of the “transparency” in reporting they offered. “When I started doing the column, it was the height of Monicagate,” he says, referring to the Monica Lewinsky scandal. “And it was a high point in public distrust of the press. There was this famous Steve Brill piece about deplorable sourcing in all the stories. So I was thinking about ways in which I could demonstrate some sort of accountability—and links became a handy way to do this.” He links frequently to documents, especially, he says, when he thinks “readers will be inclined to think I’m full of it.” Readers do scour the documents, frequently calling him on the carpet for differences in interpretation. “I love that,” he says.

Another simple online device that Slate has maximized is e-mail. Everybody uses it now. It’s the “killer app” of the Internet, says Weisberg. Yet few online publications use the voice of e-mail—combining, as Kinsley says, “the reflectiveness of writing with the spontaneity of talking”—as extensively as Slate. The magazine has developed a number of e-mail driven features—the Breakfast Table, Dialogues, Diaries—that enable fascinating people to share what’s on their minds in an informal way. In one Dialogue, for example, noted brain scientist Steven Pinker debated the concept of human happiness with psychology professor Martin Seligman. In another, this month, liberal hawks like Christopher Hitchens and Thomas Friedman reflected on whether they still supported the Iraq war.

That informal e-mail voice has carried over into the rest of the magazine. One of Slate‘s highlights over the years was author Michael Lewis’ brilliantly funny dispatches from the Microsoft antitrust trial in 1998. While the rest of the media diligently chronicled the complex ins and outs of the case, Lewis riffed on the personalities and dynamics he saw. “Today Microsoft’s lawyer John Warden established beyond a shadow of a doubt that employees of Netscape (‘Netscayup‘) have funny names,” he wrote one day.

While links and e-mail have shaped Slate‘s journalism, the magazine has evolved to take advantage of yet another tool enabled by the Web: speed. But it is one that presents a critical tension. Can a magazine like Slate, whose raison d’être is thoughtfulness, churn out material in keeping with the instantaneous standards of the Web? Weisberg, who has been pushing writers to work faster, insists it can.

Warp-Speed Journalism

I meet with Slate‘s new editor in the Microsoft enclave for “content” products known as the Red West Campus. The low-slung building that houses Slate looks like all the others in Redmond, with no sign of the magazine’s presence. From the lobby, you can see through glass doors to a banner that welcomes you to Microsoft and promotes “Innovation in a Wireless World.” Everyone floating in and out is wearing a Microsoft badge. Slate occupies only a small corner of the building. Fifteen Slatesters work here, another 17 work mostly in New York and D.C. The business and technological guts of the enterprise are here, but its editorial center of gravity has shifted East with the move of a few key people and the appointment of Weisberg, who is based in New York.

The geographic shift underscores Slate‘s mind-set from the start. It was here because Microsoft was here, and that was it. For all the ballyhoo about Kinsley migrating here, the magazine never integrated itself into the local intellectual culture. With the exception of publisher Krohn, who is a member of the Washington News Council, Slatesters haven’t mixed much with local journalists or political figures. In fact, says Shafer, who for a long time served as Kinsley’s deputy editor, “it was always the plan that Mike and I would move back. . . . There is something about working in Seattle that’s akin to floating in an archipelago out in the Pacific. You are several days behind the latest news and gossip coming over the mojo.” In 2000, Shafer returned to D.C. More surprising is that Kinsley became a Northwest convert and stayed.

While living in New York, Weisberg periodically visits Redmond to meet with other staffers, which is why he is here now for a few days. One of Slate‘s first hires, Weisberg came from New York magazine and served as Slate‘s chief political writer before taking over as editor. He has since been riding a wave of success. Readership has doubled since he took over, a fact he attributes in part to the momentous news that has been occurring and in part to Slate‘s increased emphasis on subjects like television, food, travel, and art. Other than that, he has not radically changed Kinsley’s vision for the magazine. He confesses he is a “Kinsley disciple,” having worked for Kinsley at The New Republic.

An affable but to-the-point 39-year-old, Weisberg discusses Slate‘s increasing emphasis on timeliness. “When we started it,” he says, “we had in our heads the model of a weekly magazine. Mike really thought that what the Internet would do is give us an innovative delivery system—you’d be able to get a weekly magazine right away. You’d be able to get it in a variety of formats. But mentally, we were still thinking The New Republic, The Economist—a weekly magazine. It took us a while. But we’ve come to something entirely different. The best description is a daily magazine, although in some ways we’re more like a wire service.”

This quickening of Slate‘s metabolism, as one writer puts it, came about after the magazine was caught behind the curve. That was in August 1997, when Princess Diana died. While the Net exploded with the news, Slate‘s site stayed dead for a week. Like East Coast weekly magazines, Slate had shut down the office for the last week of August and everyone had gone on vacation. It wasn’t the most important story in the world, perhaps, but it served as Slate‘s wake-up notice to pick up the pace.

The magazine began to post new material every day, then several times a day. Now, Weisberg says, the running joke is that “the magazine isn’t the type of publication to react immediately and write thoughts off the top of our heads—we wait an hour.”

“Everything that you know about writing tells you that you do sacrifice something by trying to be so quick,” Weisberg acknowledges. “Yet my own experience as a writer, and I think that of a lot of writers here, is that the things you write in a very limited amount of time are not worse but in fact better.” The spontaneity of Web journalism, he maintains, more than compensates for the lack of time to think.

More than anybody else at Slate, Mickey Kaus practices this warp-speed form of journalism. He writes a mostly political blog called Kausfiles, which, like its peers, serves to publish thoughts as fast as they can be written down—or, as Webbies like to say, in real time. To get his musings on the Web as quickly as possible, Kaus is not edited. With a click of the mouse, he posts his own material along with a promotional teaser on Slate‘s home page.

Probably the first blogger from the mainstream journalism world, Kaus says that he had hoped that by getting in early, he could influence the national debate. In the next day’s coverage of an event, Kaus hoped, the mainstream press would have to respond not only to the event itself but to what he had to say about it. “It’s not clear that’s really ever worked,” he admits, speaking by telephone from his base in Venice, Calif. But he thinks he has an impact at least on second-day stories.

Kaus also believes that he and his fellow bloggers have played central roles in keeping stories alive after the mainstream press has moved on—for example, former U.S. Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott’s approbation of onetime segregationist Strom Thurmond, and the doubts about erstwhile New York Times editor Howell Raines in the wake of the Jayson Blair scandal.

At the same time, Kaus says, he’s recently confronted the fact that speed is a limited virtue. Shortly before Al Gore gave Howard Dean the nod in December, Kaus heard a rumor that a big endorsement was in the works. “I had a little item, ‘Gee, there’s some secret endorsement in Cedar Rapids,'” he recalls. He couldn’t get any more specific than that, though he had spent a whole day trying to track down the players in order to get the word out 24 hours before everybody else. “What did I contribute?” he asks. Scooping the competition, he adds, is “fun while it’s happening but doesn’t have much lasting value.”

Can Slate deliver lasting value in the few hours it gives itself to write stories? Much as Weisberg insists that speed does not necessarily affect quality, there are some things you just can’t do in a limited amount of time. You can’t write comprehensive pieces that dig deeply into a subject. You can’t do investigative reporting beyond the nugget or two you can find out in a day. You can’t craft a sprawling narrative that takes you into somebody’s life. These are all things that other members of the club—The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Harper’s—routinely deliver. Slate only occasionally has such ambitions, and it does so by chipping away at larger stories in serial dispatches, like David Plotz’s multipart chronicle of a sperm bank seeded by Nobel Prize winners.

But then, trying to blend thoughtfulness with speed, Slate truly is a different kind of club member, a creature of its medium. As Washington Monthly‘s Glastris says, Slate has “fresh but perishable content.” Slate is the place to go to chew over the latest currents of thought, or when something happens and you want to figure out why, or how, or whether it’s a good thing or a bad one. Around the magazine’s offices, staffers like to quote the late journalist A.J. Liebling: “I can write better than anybody who can write faster, and I can write faster than anybody who can write better.”