YOU KNEW A DIFFERENT Elliott Smith than I did, because we all knew different Elliott Smiths.

You knew him at a Heatmiser show in Portland, 1993. Your sweater was torn along the bottom. So was his. You knew two sides of a cassette tapeEither/Or on one, XO on the otherthat got you through an afternoon of sorting three generations’ worth of attic clutter and finding memories you didn’t even know you had. You knew him in Bostonyou called out a request for “Last Call,” and he shook his head and said that song had too many words (but he smiled when he said it). You knew Figure 8, hearing it over and over up I-5 on the long drive home from your parents’ house in California. He shook your hand and was friendly after a small show at a record storeyou knew him then. You began to think that maybe you didn’t know him when he performed his song from Good Will Hunting in an ill-fitting white suit at the Academy Awards. You knew him at the Showbox a few years back, starting and stopping painfully. He couldn’t remember the words, and you yelled them out for him, fan as director, feeding the actor his lines. You knew him when you went down Division Street in Portland and through “Alphabet Town” in New York City.

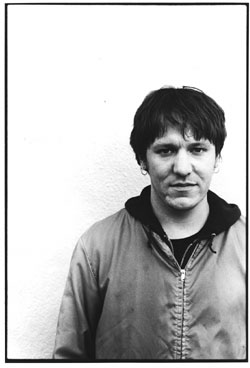

I knew Elliott Smith as a hunched figure on a stool in the mid-’90s on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, at Brownies on a too bright summer afternoon, and I remember thinking that it didn’t seem like the sun and Elliott Smith could be out on the same day. I walked up to him at the bar, just a stupid fan, and placed my hand too close to his, said hi. He withdrew a little, the first sign that I had come too close. I was already an invasion. I asked him about a cover he was doing quite often in those days: “Thirteen” by Big Star. A great song, we agreed. But he was uncomfortable, kept spinning his whiskey tumbler, the ice melting, his drink becoming weaker the longer I stayed. He scratched his head and pulled his wool cap down over his eyes, and I took my cue, thanked him especially for “No Name #1” because I always believed that the song was for me. And then I walked away.

Years later, with a jolt and the memory of a lonely drunk at a lonely bar, I thought maybe I knew him even better when I first heard “Everybody Cares, Everybody Understands” from his major-label debut, XO.

“You say you mean well, you don’t know what you mean/Fucking ought to stay the hell away from the things you know nothing about,” he sang.

As often as you felt like you should stay away, you were pulled inside. In a 2000 interview, he described himself to Rolling Stone as something of a nomad. “I just like moving around, just because, you know, you only live once,” he said. And you felt lucky that he called your town his. You knew him, living once.

In 1999, the British music magazine NME asked Smith what song described him best. His answer: “Success Can Only Fail Me Now” by his ex-bandmate Sam Coomes’ band, Quasi, with whom Smith frequently toured.

“It doesn’t have any words,” he said, “but that’s kinda the best part.”

Like the Quasi song, Smith’s death didn’t have any words. He left no note. But the way he apparently chose to go was quite a statement. A fatal knife wound is not easy to inflict. It’s no secret that Smith knew his way around serious drugs. An overdose would have been easy. Maybe too easy.

IT’LL BE AT LEAST a month or so before a toxicology report surfaces. At least a month before we can hear what he was working on before he died, what he could not complete. Web logs teem with fans’ memories. Every music magazine on the planet will mention his death, his birth date, his birth name, his Oscars appearance.

Over the next 12 months, suicide will take 30,000 Americans, and on any given day, 1 million Americans will be in treatment for drug or alcohol abuse. Sixteen percent of the American population will suffer depression debilitating enough to necessitate treatment.

And for years to come, we will ponder our romantic notion of the depressed, the sidelined, the afflicted, the maimed, the shy. We will wonder about suffering and whether it is truly necessary for good art. We will play the last track off of his last release because it is called, simply, “Bye.” And we will wonder if we ever knew Elliott Smith at all.