THE DIVINE COMEDY

THE VELLS Crocodile Cafe, 206-441-5611, $12/$10 adv. 9 p.m. Fri., Jan. 24

I CONFESS, I’M JEALOUS of Nick Hornby. We have similar, highly personal, approaches to writing about pop music, and thus sometimes I can’t help but feel envious that his musings spawn best-sellers that get turned into major motion pictures, while mine are, well, buried in the back of Seattle Weekly. Consequently, I was reluctant to purchase Hornby’s new collection of reminiscences, Songbook (McSweeny’s Books). But then one night, I was browsing at Bailey/Coy Books with a $6 store credit to burn, and oops, it happened.

Much to my chagrin, I enjoyed Songbook, particularly the piece concerning “I’m Like a Bird” by Nelly Furtado. Furtado’s music may make me curl up like a pill bug (then again, I loved Mandy Moore’s “In My Pocket,” so perhaps I shouldn’t throw stones), but regardless, I was suckered in by Hornby’s opening paragraph. He began by saying he appreciates people who dismiss pop as “trashy, unimaginative, poorly written . . . ,” etc., because he also recognizes most of it as such.

“I know, too, believe me, that Cole Porter was ‘better’ than Madonna or Travis, that most pop songs are aimed cynically at a target audience three decades younger than I am, that in any case the golden age was 35 years ago and there has been very little of value since,” he continued. And that was a sentence that made me cheer, however much I dissented with the pro-Furtado essay that followed.

You see, after years in the trenches, I’m getting fed up with folks who hold up Porter, Rodgers and Hart, and a select few other antiquated composers as the standard-bearers against whom contemporary songwriters must be measured. Because the truth is, there are still folks writing material of equal, or superior, caliber. Living, breathing artists—some with full heads of hair—who still manage to attain some commercial success. Folks like the Divine Comedy.

Don’t be embarrassed if you only associate the name the Divine Comedy with Dante’s epic poem. While this British ensemble, led by Neil Hannon, have been active since the early ’90s, only a couple of their albums have been released in America. (The 1999 retrospective A Secret History is a great place to start before shelling out big bucks for the imports.) And although Hannon crafts some of the most literate lyrics ever committed to record, the Divine Comedy have scored honest-to-god chart hits overseas. I remember seeing them open for Robbie Williams at a stadium-sized Dublin venue in 1999, and the crowd actually sang along with “National Express,” Hannon’s tongue-twisting homage to travel by British rail. Meanwhile, in the U.S., the only civilians who can parrot that kind of verbal dexterity with ease are the Eminem wanna-bes on TRL.

One of the biggest obstacles that prevented Hannon’s rich baritone and savvy songwriting from reaching American ears for years was purely logistical. The Divine Comedy’s classic lineup was seven members strong. Hell, their 1997 mini-LP, A Short Album About Love, featured a 30-piece orchestra. In short, the Divine Comedy were not the kind of band that could tour our vast nation in a van for six months until they built up some buzz.

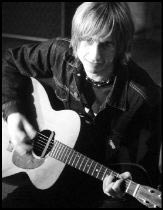

All that changed in 2001. Hannon said he got tired of being seen as the “suit-wearing little man with big voice trying to be Burt Bacharach.” Although Regeneration (Nettwerk America) didn’t represent Hannon’s attempt to, as he memorably sang in one cut, “Dumb It Down,” for their seventh album, the group ditched the flutes and flgelhorns for a more trad rock sound, shaped by producer Nigel Godrich (Beck, Radiohead), and traded in their tailored threads for jeans and sneakers. Just before the U.S. release of Regeneration, Hannon decided to pare back even more and dismissed the other six members of the band. When the Divine Comedy finally toured the States extensively, in the spring and summer of 2002, it was as a solo act.

Although Hannon’s hair has gotten longer, and his band smaller, a couple key aspects of the Divine Comedy have remained the same. First, he continues to write stellar songs, as evidenced by the new tunes (“Boise,” “A Mutual Friend”) featured at his Moore Theatre warm-up slot last March. So hopefully, when he plays the Croc this Friday, he’ll treat fans to more recent selections from his forthcoming album, due later this year.

Also, after much consideration, Hannon has decided to keep working under the Divine Comedy moniker. In a message on his Web site, the artist conceded that after a decade-plus of gigs and records, the name boasts a certain degree of brand recognition. “Besides,” he concluded in the same post, “Neil Hannon is a sucky name for a pop star.”

I disagree. “Neil Hannon” is a hell of lot better “Nelly Furtado.” And I mean that in more ways than one.