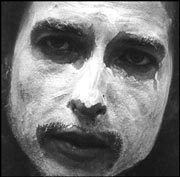

HENRY ROLLINS

Moore Theatre, 206-682-1414, $21-$23.50

8 p.m. Fri., Jan. 10

“TO ME,” SAYS Henry Rollins, “the way to really get close to the material is to go at it from almost an insane or an absurdist angle. If you just go for the straight facts, you know, they kind of come up to meet you with a fist in the face. It’s like the idea of us getting into a war with North Korea. I can’t see it happening, but the way for me to internalize it is to envision these old guys running around the war room with hard-ons, looking for some payback for when they had to bail out of Pusan in the ’50s. Or Donald Rumsfeld’s thing: ‘Yeah, we can handle two wars! Absolutely two wars! How ’bout fuckin’ three? Come on, you motherfuckers, we’ll start two half-wars over at your house, and we’ll have another one on the White House lawn right now, bitch!'”

To quote at length from Rollins’ interview-opening diatribe would be to give away the store—he is, after all, about to embark on a 50-date spoken-word tour—but suffice to say that 30 minutes in Henry Rollins’ phone presence plays like a mini-concert unto itself. As well it might: The man who once self-deprecatingly billed himself as the Big Ugly Mouth now has almost two decades of talking shows to his credit.

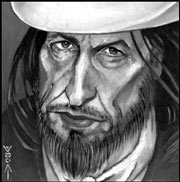

It was a practice that was very nearly without precedent in the mid-1980s, when Rollins began making solo speaking appearances between gigs with Black Flag, L.A.’s standard-bearing hardcore punk outfit. Rollins’ talking shows of that period were much like his lyrical work—brooding, intense set pieces, rooted in a nearly maniacal and always unsettling self-awareness. Detractors who dismissed him as a hypermasculine poseur aimed extremely wide of the mark, seeing only the thousand-yard stare and the tattooed biceps and missing the raw, red heart beneath. At his best, which was remarkably often, even the very young Henry Rollins was a word artist in the vein of ’60s iconoclast Brother Theodore, whose ferociously delivered monologues about life in the modern city gave voice to a culture’s largely unspoken feelings of frustration and alienation. If his shows often made for uncomfortable listening, it was because Rollins—like the Beats—believed that all topics, including his own considerable pain and rage, were suitable subject matter for public discourse.

After two decades in the trenches, Henry Rollins hasn’t lost his anger or his formidable timing. His marathon speaking shows, however—which frequently run to the three-hour mark—have gradually become less self-antagonizing, more finely attuned to the possibilities of survival through damage, and not simple damage itself.

“That’s how you try to keep your head through it. You want to stand there and be able to laugh—not at it, and not with it, but close to it. Like one parking lot away from it. Otherwise you become a Wolf Blitzer type: ‘Well, the Amurrican people,’ blah, blah, blah.

“You look at Dr. Strangelove,” he continues. “That, to me, is the perfect movie—perfectly cast, perfectly written, perfectly directed—and says a lot more about war than even a film like Apocalypse Now or Full Metal Jacket. With the exception of Peter Sellers as the young R.A.F. captain, who’s the only one trying to hold it together, everybody in that movie is completely insane. And recognizing that absurdity allows you to get close without getting shut down, to where you can no longer get the material or really assess it.”

HENRY ROLLINS has always kept a full work slate, but perhaps the most remarkable of his recent projects is the Rise Above compilation album, whose proceeds benefit the defense fund of the West Memphis Three, the trio of Arkansas teens who were convicted of murder in 1993 under exceedingly dubious circumstances (see the group’s official Web site, www.wm3.org, for a full recounting and updates).

Rise Above features 24 Black Flag songs performed by the Rollins Band and guest vocalists such as Chuck D., Iggy Pop, and former Flag vocalist Keith Morris, and represents the first time Rollins has performed Black Flag material since the group’s breakup in 1987.

“I thought it would be fine,” Rollins says of the album. “I didn’t think it was going to come out that smokin’. The record really whups that ass—but it’s great songs, well played, sung by cool people. You can’t lose. But we all were kind of surprised. We just kept listening to each playback, going, ‘O-kayyy . . . I guess that worked.’ But it’s Greg [Ginn’s] and Chuck [Dukowski’s] writing. They wrote some great songs.”

Likewise, a series of sold-out shows at the Whisky a Go Go brought Rollins together with former bandmates Morris and Kira Roessler. “We opened with ‘Nervous Breakdown,’ and Keith walks on. People damn near shit. We go into ‘Annihilate This Week,’ which Kira was a big vocal part of, and she comes out onstage—no one in the venue knew she was there. I hadn’t played with Kira since 1985. Everyone in the place freaked. And we raised $10,000, which is going to be put directly towards DNA testing in the West Memphis Three case.”

Since learning of the case through the documentary Paradise Lost, Rollins has been active in raising awareness about the West Memphis Three. “But what I’m discovering is that the wheels of justice turn very, very slowly, if they turn at all. I don’t want those boys to be released on a technicality, like Jessie Misskelley not being given his Miranda before his questioning. I think they’re slam-dunk innocent, and I’d love for that to get proven in court, with the state having to pay them many millions of dollars. Those years, when you’re between 16 and 20, are supposed to be the time of your life. Those are the years when I was playing shows and going to cool places, when the girl leaves you and you cry and scream and all that . . . as opposed to my age now, where the girl leaves, and you grunt and throw something in the microwave and go back to check your eBay bid. These boys are spending those years with murderers and rapists in a tiny room with no natural light. Even if they are released, something’s been taken away from them that they can’t be given back. But we’re fighting a good fight, and it looks like there are bright spots on the horizon. We hope.”

FOR A MAN who once mused that he might have four more albums left in him—this was several albums and books and spoken shows ago—Henry Rollins seems to find that the more work he does, the more there is to do.

“I think so, definitely. With the writing, mostly. Editing is a bitch, which is the reason most writers are assholes,” he laughs, “because it’s incredibly hard work. Not like when you were young and wrote down everything that came to you. You keep learning how little you know. All I can really hope is that I’ll be smart enough to know when I’m done. I don’t want to hang around after that. But then there’s Henry Miller—I have a copy of Black Spring in my bedroom right now—I can’t read a page of Miller without wanting to get up and go write. The guy had an ‘on’ switch that he tripped when he was 35, and he didn’t go ‘off’ until he died. What a testimony.”

To what?

“To living. To living until you stop.”