THE LAST TRUE BELIEVER

Seattle Center, Seattle Repertory Theatre, 443-2222, $10-$44 7:30 p.m. Tues.-Sun.; 2 p.m. matinees Sat.-Sun. ends Sun., March 24

TOLD YET AGAIN that his father, a spy who died under murky circumstances, simply committed suicide, protagonist Kevin Anderson responds, “That argument’s very stale.” Ah yes, my boy, it is, and, unfortunately, it will continue to be for the next two hours. Robert William Sherwood’s The Last True Believer, a world premiere that opened last week at the Rep, has an idea about how dangerously unsettled the world’s post-Cold War angst has left us all—and, yawn, it remains an idea.

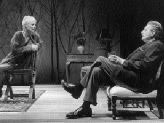

Kevin (Coby Goss) has come to London to delve into the mystery of his father’s demise and ends up trudging through a mire of political and social ambiguity, including the possible duplicity of his father’s oldest friend, rigid old-school diplomat Philip Daniels (Terence Rigby). Hoping that an answer will clear up concerns about his own fragmented existence, Kevin is ready to wage war with the man. Daniels, meanwhile, has battles to fight with his brittle, melancholy wife, Margaret (Lisa Harrow), who has her share of furtive regrets. Oh, and an East German colleague of Daniels (Peter A. Jacobs) pops up to pronounce his “w”‘s like “v”‘s and refer to bad U.S. beer as “zis Amer-i-can dreenk.”

Sherwood has pointed questions about who we are in a world less and less sure of its beliefs, but he’s a little stilted in the asking, and you don’t buy any of it. Believer resembles some stiff drawing-room thriller from the ’50s, in which veddy proper people fix themselves scotch and volley clipped, stinging accusations at one another from across the room. Every speech is either an explanation or a request for an explanation. Sherwood seems so intent on shaping his modern-day tale with midcentury aesthetics you might think he’s winking at you: When Harrow enters and proclaims, “I’ve been out in the garden—the dahlias are in bloom again,” you could swear he’s kidding.

Director Leonard Foglia’s forced hand with the verbal tennis matches doesn’t help loosen things up. No one’s really talking to each other; almost everyone on stage looks grim and dutiful, as if politely waiting for a chance to speak. Goss can’t find a way to portray a man self- described as “a handshake, a haircut, permanent pressed” and spends the entire first act clenching his jaw and demand- ing “Tell me why . . . !” in weepy anger. Harrow, a fine actor, has magisterial presence, but except for a sorrowful, accusatory rage late in Act II, Leonard has her snapping lines in half and spitting them out to no one in particular (a problem accentuated by Rigby, whose stolid British reserve appears to be on autopilot).

The only person who radiates any real human warmth is Liz McCarthy, playing Philip and Margaret’s daughter, Jessica. Reaching out to Kevin, McCarthy’s Jessica best conveys Sherwood’s earnest sense that our current socio-political climate now consists of people carefully hiding their shuddering confusion about the world and their uncertain roles in it. “I’m more afraid than they were,” Jessica says, reflecting on her parents’ generation to Kevin. “And I have less reason.” That’s nice, but it’s all we get. Sherwood may have an active desire to contemplate living in a world where truth is less true, but Believer is all talk.