PAT GRANEY RETROSPECTIVE

Moore Theatre, 1932 Second, 292-ARTS $25.50-$36 8 p.m. Fri.-Sat., Jan. 11-19

MORE OFTEN than not, artists don’t do retrospectives until their careers are close to the end. Though this guarantees a big chunk of material to work with, it comes with a sad feeling, like reading the last book by an author who won’t write any more. As usual, Pat Graney has got it right, providing us with a midcareer look around, a chance to remind ourselves of old favorites while we can still hope for more.

The work on last week’s program stretches back almost 20 years. Table, from 1983, is an almost textbook example of deconstructing pedestrian material—in this case, a standard business meeting—slowing it down and breaking it up into tiny pieces like the movement equivalent of the phoneme, each moment distinct and almost meaningless until strung back together with the others and brought back to normal speed. The bits become a whole, and the erratic ticks and twitches of the dancers become ordinary social behavior. Up to this point, the work would be a perfectly reasonable assignment in a composition class, but Graney continues to play with speed and agitation so that we start to wonder if we were really just seeing these people in a slowed-down film, or if they are truly disturbed.

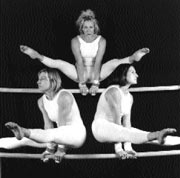

This happens repeatedly in Graney’s choreography—she begins with a relatively simple idea only to add layer on layer of detail and reference until we question the original premise and see that world with a changed perspective. In 5/Uneven (1989) she is drawing again from existing movement, this time the grueling practice of gymnasts on the uneven bars, and for a great deal of the piece we are caught up in their skill and strength. By breaking up the longer movement phrases, Graney takes away the momentum that usually helps propel the athlete, and so we are shown moments from their bar routines, almost like photos or sculptures. In their white briefs and shirts, the dancers glow in the stage light, but they are strangely not theatrical—their performance is so matter-of-fact they seem to be still in a gymnasium. This impression is reinforced throughout the piece as they take breaks to drink water and chalk up their hands, and it looks like the work will continue in this vein until almost the very end, when the lights fade on a single woman perched high on the top bar. She has pressed herself up on her hands, legs outstretched while she turns slowly from side to side. From the gym to our imaginations, she could be almost anything: a weather vane, a lookout, a flag left out after sunset. We’ve moved from pedestrian to metaphor in a heartbeat.

When she’s not manipulating movement taken from other sources, Graney’s actual “dance steps” are relatively simple. It’s the structuring of those steps that is the challenge for the performer and for us. In Colleen Ann (1986), which will be performed this weekend, she takes a shorthand version of Irish step dancing and combines it with American Sign Language. As the dancers literally “tell” the story of Graney’s family and their migration to the U.S., they hop and stamp, but their timing is more complex than the straightforward series of 8s that we know from Riverdance and its descendants. It is disturbing in a subtle way. Mitzi’s Dance, which premiered last weekend, also draws from a folk dance vocabulary, a curious blend of step dancing, flamenco, and Balkan material. Instead of the Catholic schoolgirls of Colleen Ann, these women, wearing sparkly dresses and swishing their skirts as their heels hit the floor, could be our mothers back when they dressed up for a party. Giggling and chasing each other, their competition comes close to confrontation but never goes over the line.

In Pagan Love Song (1989), Graney takes the image of the bathing beauty, male and female, and smartly trots it around the stage to a bubbling W.A. Mozart score. We laugh at first, simply because they look so silly, all these women in skirted bathing suits and colorful caps, and men in Charles Atlas singlets. But as they continue to wheel and slice through the space, the nonsense wears off and we see that they are actually a corps de ballet, in the same kind of flanking maneuvers that we might see in Swan Lake or Nutcracker. Graney has taken Marius Petipa to the beach, and after solidly establishing herself as a contemporary choreographer, she’s reminding us that her roots go much further back.