NOVOCAINE

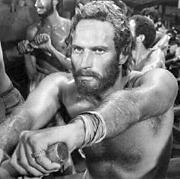

written and directed by David Atkins with Steve Martin, Helena Bonham Carter, and Laura Dern opens Nov. 16 at Metro and Uptown

STEVE MARTIN’S SIDE career as a straight man continues with this idiosyncratic and darkly comic noir that aims high but hangs itself on the line between homage and parody. The dichotomy seems appropriate for Martin, the stand-up comic turned movie star turned novelist and playwright who’s been on a quiet but dogged search for respect ever since he broke into show business writing gags for the Smothers Brothers some 35 years ago.

As a flawed but basically decent dentist named Frank, Martin adapts the subdued demeanor and deadpan delivery of any number of noir antiheroes, while freshman writer-director David Atkins alternately plays with and against the genre’s clich鳮 “The worst thing a man can lose,” says Frank in voice-over, “is his teeth.” It’s a perplexing but tone-setting line; film noir’s gravity is reduced to a cavity, its world-weariness riddled with absurdity. Novocaine coalesces only when—or if—one discovers that the statement is really a punch line.

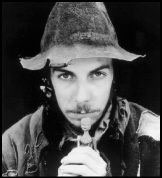

Engaged to his obsessive hygienist, Jean (Laura Dern), Frank gives in to a dentist’s chair dalliance with ragged minx Susan (Helena Bonham Carter), whose sawed-off brother (Scott Caan) involves him in dope dealing and murder. Caan’s turn is too short to be more than one careening note, but Novocaine‘s women complement each other remarkably well. Bonham Carter, recalling her Fight Club days, lends an alluring sleaze to her femme fatale, while Dern’s martial sexuality is no less inciting.

Atkins takes perverse pleasure in having Martin’s character bang two babes, no doubt. Similarly, he puts Martin through his Hitchcockian paces—the 56-year-old flees cops, scales rooftops, and navigates all sorts of other chaos—before a macabre finale.

But despite the initial energy, style, and invention of Atkins’ premise (all put to Danny Elfman’s bombastic score), his overplotting overwhelms his ensemble. One intrusive detour involves an uncredited Kevin Bacon as an egomaniacal actor studying the police; it offers some value as comic relief—but none as a red herring. A much more important subplot concerns Frank’s wayward brother (Elias Koteas) but only adds layers of confusion and implausibility to underlying double crosses and shifting loyalties.

In this way, Atkins may be covering his tracks, turning us around so many times that we lose sight of the holes in his story. But given Novocaine‘s many sly nods and self-referential moments, he really seems to be sending up those film-noir classics in which the hero’s every move sinks him deeper into moral muck. His movie’s finally an intellectual exercise, a genre study lacking in spontaneity—particularly next to The Man Who Wasn’t There—but still suited to the Renaissance man Martin.