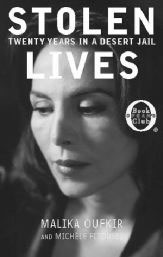

STOLEN LIVES: TWENTY YEARS IN A DESERT JAIL by Malika Oufkir and Michele Fitoussi (Hyperion, $24)

BEAUTIFUL WOMEN, gorgeous palaces, daring escapes, and plenty of bad guys: The particulars of Stolen Lives: Twenty Years in a Desert Jail, the autobiographical tale of Malika Oufkir and her family, belong in the latest 007 thriller. Indeed, by choosing this book as her May Book of the Month Club selection, Oprah Winfrey has nearly guaranteed it will show up at your local cineplex— or at least on your TV screen—soon. Read as a treatment for a film or miniseries, Stolen Lives is a perfectly entertaining and breezy—if bleak—summer read. But if you stop to think about the book, you may find you have more questions than answers.

Co-authors Oufkir and Michele Fitoussi, the literary editor for French Elle, tell this harrowing tale like an old-fashioned daily newspaper story: who, what, where, when. Annoyingly, they never get to why: What does it mean, or so what? Still, it’s a gripping story.

Oufkir recalls being raised with a level of privilege that makes George W. Bush’s upbringing seem indigent. Her father’s a big muck-a-muck in the Moroccan government (a monarchy?—the authors fail to give even the most basic primer on modern Moroccan history), and her mother is upper, upper-class as well. At 5, Oufkir’s “adopted” by the king as a companion for his daughter in a type of feudal family bonding arrangement. She lives in a series of palaces, where she’s taught by governesses, surrounded by concubines, and pampered by every means possible. When the king dies, his son takes over but continues to care for the girls in a similarly lavish fashion. Finally, at 16, Oufkir objects to her forced separation from her family, which has now swelled to include five other kids. She receives two years at home, and spends a good chunk of the time sneaking out to dance clubs and flitting off to Paris, whooping it up ’60s-style. But in August of 1972, her father attempts a coup and is shot. Oufkir, her mother, her siblings (the youngest a 3-year-old boy), and two family retainers are immediately bundled off to the first of a series of grim desert jails, where they remain for almost two decades.

THE MAJORITY of Stolen Lives details the painful reality of staying sane and alive under concentration camp-like circumstances. While the Oufkir clan’s general fortitude is laudable, their story feels one-dimensional without the context of what was going on politically in Morocco and the rest of the world—or even within the family. Oufkir mentions that her mother, who’s much more independent than the average Moroccan woman, was “the only person to stand up to . . . [the king] and defy him,” but never says when and how this happened. Likewise, she doesn’t discuss her father’s politics, nor does she elaborate upon brief references to other political prisoners and former friends who abandoned the Oufkirs once they were incarcerated. You could argue that background information doesn’t matter—of course imprisoning children is wrong, and the politics behind such an act are irrelevant. But this would be a much more compelling book if Oufkir had grasped the whole story, and made us understand what happened and why.

Perhaps Oufkir’s arduous experiences in jail—acting as her family’s support and protector, standing up to the guards, fighting for every scrap of grub-riddled flour, creating complex fantasies to distract and entertain herself—has left her unable to fully explore her memories. A little more distance from her imprisonment might have helped, but she was desperate to get the book published before the king died. She got her wish, but was her goal revenge, retribution, an apology, an explanation, or even lasting change to Morocco’s political system? Like too much of Stolen Lives, the answer remains unclear.