Herewith, the five “easy” steps that made Seattle Weekly—or, at least, the steps that happened during the 21 years that I was its editor or publisher. You might detect a master plan in all this, but believe me, at the time it just felt like improvisation to a tune we didn’t know existed until we made it up.

1. In 1976, it had been a half a decade since the city had a quality magazine, so there was considerable appetite for one more try. This time, rather than an expensive slick monthly, (three of which had recently failed), we decided to be more topical (weekly) and more affordable (newsprint, not slick). It was also cheaper to start this way, so off we went in our first offices, a former gypsy shoe-shine parlor that is now the Bookstore Bar in the Alexis Hotel. We lacked money, but not ambition—modeling the rag on The New Yorker, The New Republic, and Atlantic with their insiderish, literary, knowing tone.

Speaking of The New Yorker, we stole the idea of critical calendar listings from that magazine—which meant hiring good arts writers to pull it off. The dailies duly copied this idea but, before they caught on, evaluative and reliable listings really launched the second generation of alternative weeklies (antiwar politics launched the first generation).

The other launching idea was personal classifieds, which we started as an afterthought and immediately discovered produced much of the best writing in the paper (for obvious reasons). We never even made up one ad, I swear.

Our first designer, Terry Heckler, convinced us to use conservative Swiss newspaper design, with squared-off ad blocks (not zigzags) to bring visual order to a tabloid page cluttered with small ads. The advertising strategy was to give slick magazine readership at tabloid newsprint prices, and to help small advertisers reach their market at low cost and without needing an ad agency.

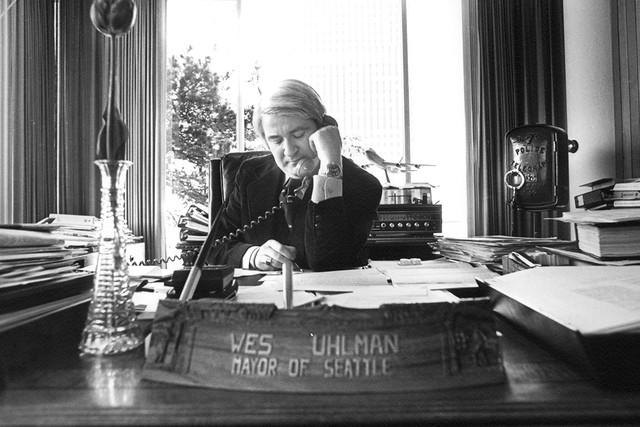

Back in the 1970s, Seattle was still an “island culture,” controlled by a local elite and very different from the globalized economy of today. Our owners, many drawn from the political and cultural leadership, gave the paper that sense of devotion to local betterment—something that would today seem too cozy, too co-opted.

2. Roger Downey, a Weekly writer from issue one, was absolutely critical to our early reputation for tough, learned, passionate arts criticism. In turn, this brought other writers—and gave the paper a key difference from the dailies. And the excellent arts coverage earned the Weekly admission to a more conservative readership than our politics would have permitted.

We also lucked out early on with literary sportswriters: Alan Furst and Fred Moody on football, Roger Sale on the Sonics and horse racing, William Dunlop on soccer, and Bruce Barcott on baseball. This was another aspect of the “literary journalism” these alternative papers (at least, some of them) were practicing, back before sports writing became more an exercise in blue-collar populism.

As for politics, the critical good luck came with editor Barry Mitzman’s discovery of Rebecca Boren, who set a style for edgy, massively informed political writing and became the best political writer in town. John Arthur Wilson kept up the tradition, which gave the Weekly a must-read reputation with the government crowd. Politics has faded in importance since then—and alternative weekly stances have become more alienated and outsiderish.

In the mid-80s, we started Sasquatch Books, building on The Best Places guidebook series I had started a decade earlier. Having a books division was an important part of being a writers’ paper, since it gave our staff a next step in their development as writers. Journalism for serious writers tends to dead-end at age 40, and I wanted to have a natural upward rise part of the appeal for coming to work at the Weekly. Back in those days, writerly journalists could not get jobs at the dailies, so alties could nab them and try to hold them. Now the dailies, too, want more opinion and edge in their reporting, so the weeklies have a harder time recruiting.

3. Our biggest non-Weekly venture was starting Eastsideweek in 1990. The gambit was to reach a bigger audience with a free publication and to tap that hot market. With these increased circulation numbers, I hoped, we could keep the Weekly a paid publication (with a more loyal audience). And we could pioneer, as Skip Berger did brilliantly, the notion of edgy journalism in the suburbs.

Voice personals came along in the last decade—one more effort by the alternative weeklies to goose revenues with a new invention (also duly imitated by the dailies). It worked for a while—as did some early adapting of the Web (becoming the portal to alternative culture)—but the days of technological innovation by the weeklies seem past, just as the days of purchase and consolidation are upon us.

At the same time, the Stranger was starting up and I made a big business mistake of ignoring its potential to attack us by being cheaper for advertisers, younger, freely circulated, and musically hip. In other cities, when “alternative alternatives” crop up, the first-born has tended to crush the rival in the crib. Poetic justice, I guess: We sneaked into town under the radar of the dailies, which scoffed at our challenge.

4. Like most editors, I tended to lose touch with the changing culture of Seattle— which had gone from Save-the-Market reformers to Storm-the-WTO radicals. Silly me, I thought alternative culture was fading, when instead it was becoming an essential part of the new blended bohemian/bourgeois (or BoBo) lifestyle. The Weekly was born at a time when we middle-class strivers were trying to master the high style. I knew it was time for me to lay down my editing pencil when it became clear that low, transgressive style was the new mark of success— the sure sign that the new elite was not going to resemble the overthrown WASP elite, even if it was richer and more materialistic.

So, over my objections and belatedly, the paper shifted to free circulation like all the other weeklies in the country. That made it a different, younger, broader paper—and it needed an editor who liked this kind of formula. And, as I feared, it meant that the original ownership of the paper grew less connected with the paper, and less willing to invest in its growth.

5. Which brings us to the last step in Weekly-making on my watch: sale to the Village Voice/LA Weekly folks in 1997. That brought new capital and marked a natural end to the “island culture” phase of Seattle and this paper. The alties are now an essential part of hip cities, preserving the anthems of resistance that accompanied their birth 30 years ago. For me, it was great fun doing it with a marvelous set of colleagues. That the outcome was different from my imaginings only goes to show that newspapers properly reflect far more powerful social dynamics than are imagined in one editor’s philosophy.

David Brewster founded Seattle Weekly in 1976 and was its editor and publisher until 1997. He now is executive director of Town Hall Seattle, a cultural center on First Hill devoted to the arts and discourse.