IN CASE YOU’VE been living under a rock for the last few years, swing is back with a vengeance. Whether it’s reissues of classic discs, or new recordings by the likes of Brian Setzer or the Cherry Poppin’ Daddies, swing music and the dancing that goes with it have made a stunning reappearance. Local dance studios are full of wanna-be lindy hoppers learning the distinctions between East and West Coast swing, while PBS pledge sessions are packed with ballroom dance extravaganzas. Swing, the Broadway music and dance review arriving in Seattle, is just another sleek example of this phenomenon’s resounding popularity.

Swing

January 16- 21 at Paramount Theater

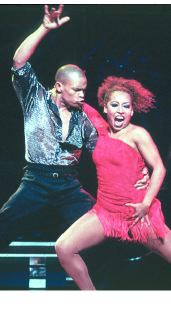

A descendant of 1920s jazz, swing music—and the syncopated rhythms from that time period—is signified by the distinctive way a swing dancer pounces on the downbeat. It’s no coincidence that the development of swing overlaps one of the great eras in tap dancing; they’re both about playing with timing. In the lindy hop, as in many swing-era dances, you see the upbeat reflected in the shoulders of the performers, like a little gasp before they launch themselves into the next step, or like a skier at the top of a slalom course. As this phrasing repeats, we start to bounce along with the pattern, and this powerful motor is the connection between the dancers and the audience. The incredible gymnastics of the partnering are stunning, occasionally making Jackie Chan look like a featherweight, but it’s the rhythm that holds it all together.

Like Dancin’ and Smokey Joe’s Cafe, Swing is more a collection of song-and-dance numbers than a book musical. Some of the sections are staged almost as they might have been originally, with smooth vintage choreography for the vocalists matching the liquid quality of their harmonizing. But historical accuracy is not the major goal of the production—a few of the numbers use as many contemporary tricks as they can manage, including something suspiciously similar to bungee jumping. In this context, swing dancing seems like a precursor to the “high-risk” choreography of Eduoard Locke or the uncompromising gymnastic challenges demonstrated by Elizabeth Streb.

Scholarly types have several explanations for the current interest in swing. There’s our nostalgia for the World War II generation and its culture, enthusiasm for athleticism and virtuosic movement, or just the infectious quality of the rhythmic patterns themselves. Whatever the actual reasons, with a playlist that reaches from Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman to Hoagy Carmichael and Count Basie (with stops for Harold Arlen, Louis Prima, and Johnny Mercer) and choreography to match, Swing looks to be a riotous survey of a fabulous era in song and dance.