EACH MORNING he boards the bus in his customary fog. He is never ready for the world, its shapes are too sharp, its words too loud. Without coffee, he is nothing. With it, he isn’t much more. Each day he travels to his office where he breaks up data along hard lines that someone else created. He breaks it up and sends it into the ether. Bits of hope and art and longing and news and importance and irrelevance. Events, journeys, details, bland theories, pictures of ponies, nothing. On this day he chooses a seat near the back that seems, at first glance, safe from strangers. He is going nowhere. Just as he pushes himself into the small space allotted him for this day’s trip, into the small space where his dissatisfaction is warm and safe and comforting, he is aware of a woman’s voice behind him.

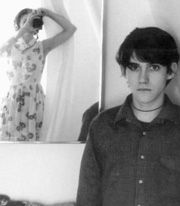

Bright Eyes

Paradox, Saturday, September 30

“Conor. Conor Oberst from Bright Eyes,” she says to her companion. “His latest record, his third actually, is called Fevers and Mirrors, and it’s amazing. He was at home in Omaha, Nebraska, when I called him. Nebraska.” Like it was the moon. That’s how she makes it sound.

“He’s just a kid, really. Only 20. But he’s been telling his stories forever. He’s sorta like Isaac Brock, Elliott Smith, Nick Drake, Vic Chesnutt. All those unlikely lotharios. You love them because they’re complicated. And beautiful. Beautiful on the inside and you hope that someday, someone will return the favor.”

She continues, “He plays guitar the way Elliott used to; slight hands banging and strumming on acoustic strings, stopping suddenly and often to pick out pretty, moody little notes. Some songs are just that: bare, acoustic, dark, and alone. Others have more layers. Pretty violin paths, choirs of organs, and sometimes odd electronic noises. And then his voice, the stories. He screams, he whispers, the stories arrest you. He obsessively creates tragedy and somehow it’s comforting. It’s unbelievable.

“He said he always feels exposed. I suppose his fans believe that the stories he tells are always about him, that they found his diary and he agreed to read it out loud. He said—” and here she rustles through her papers, looking for just the right thing. Already the man’s ears feel numb from the strain of listening. “‘People kinda want the tabloid nature of it, the depressed, drunk kid part of it. Obviously, that’s in the music, so I only have myself to blame for that, but I mean, yeah, it’s difficult because it’s not such happy subject matter.’

“He has this song, ‘Padraic My Prince’ from Letting Off the Happiness, his second full-length. It’s the story of a big brother whose younger sibling drowns in a bathtub and their mother who just lets it happen. It’s awful. Awful because you suspect that it’s real. His delivery, the pain; it’s so genuine. He said that when he was going to college, after that album came out, his classmates would stare at him and whisper.”

She rustles through the papers again and uses her read-out-loud voice, “‘Like everyone comes to see the animals in the zoo, freak shows, stuff like that. It’s like, Look how sad he is! It was fucked up, for sure.’

“Then you realize that these songs, the affliction, the rumination, the reverie, they’re mostly just tall tales sewn around some loose theories, vivid dreams, and stark metaphors. You can’t figure out if he’s a haunted genius or a depressed maniac. I guess he’s probably a bit of both.

“We talked about his depression and why his fans are so ardent,” she says, and reads from her notes, “‘There’s pleasure in sadness. There’s comfort in it. I know I can slip into times when I’m really depressed, and I could find a way to be less depressed, but there’s a part of me that enjoys it and that must be because I spend so much time feeling that way. There’s something that keeps you going back to it. That’s why people buy sad records and that’s why people watch sad movies. Maybe the same reason that people slow down when they see car wrecks on the interstate. There are people that like seeing the horrible, upsetting part of life.'”

She continues with the quote and suddenly the man has forgotten how this all started. He can’t remember where the hell he’s going and doesn’t have a clue what he is to do once he arrives. But he is calm.

She keeps reading, quoting. “‘Making music and writing these songs, there’s a healing aspect. It makes me feel better and it fills up my time. It makes it easier for me to keep on keeping on, or whatever. But there’s a part of me that wonders if I’m making it worse by dwelling on these things. Like driving around the country and singing these songs every night. Even kinda packaging your sorrow and selling it after the shows in CD form. Maybe that isn’t the smartest way to feel better.'”

The woman is quiet then. Someone pulls the chord, the bell rings, the Stop Requested sign lights up. He recalls The Thousand and One Nights, the sultan Schahriar and Scheherazade. How sometimes stories keep you alive. The morning fog is thick and dense by the city’s waterfront. It has no intention of dissipating. He feels that he is, for the first time, in good company.

For more on Bright Eyes, visit the Saddle Creek Records Web site where you may access sound files and purchase CDs.