HOW CAN THE self-respecting, eco-correct, Nader-voting, car-dependent Seattleite sop his or her environmental conscience in our prosperous, SUV-loving age? This year’s gas pump shock—like the OPEC crisis of yore—serves to remind us that smaller, cheaper transportation alternatives are now being bundled into very high-tech packages. But as with so many other utopian fantasies of the ’70s, the all-electric car has fallen by the wayside (like Yes, the ERA, and Jimmy Carter). Limited range, pathetic performance, and huge, heavy space-hogging batteries kept it from reaching mass production. Although a few manufacturers now market such vehicles, they’re expensive and unsuited to America’s lead-footed driving habits and wide-open spaces.

In their place, the year 2000 has seen the introduction of two affordable gas-electric hybrid automobiles, the Toyota Prius and Honda Insight, both of which are being marketed in the US on a limited scale. (Both also meet NTSB crash-test safety standards.)

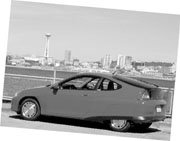

Honda reached these shores first, in December of last year, and has sold roughly 1,900 units to date, with plans to produce 6,500 worldwide this year (probably more in 2001). Priced under $21,000, the Insight is cheap compared to an Excursion, expensive compared to a Geo, but its window sticker certainly doesn’t reflect actual manufacturing costs. Like the Prius, this Insight is something of a public relations loss leader; both cars have received Sierra Club awards for “excellence in environmental engineering.” (Moreover, while Japanese hybrid car buyers receive a $3,000 government rebate, our Big Three auto makers aren’t expected to market their first hybrids until 2003—despite $1.4 billion in direct government assistance over the last five years.) You may already have seen a few of these rare, sleek Hondas cruising around the streets of Seattle— including mine.

Well, not mine, but a bright red loaner Honda used for various around-town errands and trips last week. Learning how it works, and buttonholing strangers who variously gawked and scoffed at the thing, provides some, er, insight as to whether Americans are ready for the small, light, frugal vehicle—and whether it’s ready for us.

FIRST, THE SPECS: 61 city, 70 highway—those are the official EPA mileage estimates. How does the low-emission Insight manage that trick? Its streamlined teardrop shape minimizes wind resistance. Made of plastic and aluminum, the two-seater weighs less than 1,900 pounds, requiring only a one-liter, three-cylinder, 12-valve engine producing a mere 67 bhp. That’s the first power plant. The second unit under the hood is a small parallel magnetic-electric motor attached to the crankshaft—either contributing or pooling extra power, depending on conditions.

Hence, hybrid. The Insight goes to an ordinary gas station like any other car running on unleaded fuel. Its 10 kilowatt, six bhp motor transmits energy to the nickel batteries located behind the seats—that’s all the charging you need to worry about. (And, no, you won’t be electrocuted upon turning the key.) While driving, the car isn’t silent like an all-electric model, but it is eerily quiet—lending to its space-age cachet.

During my impromptu road test, the electric power assist kicked in when needed to rev up steep, cobblestoned Virginia Street to First in low gear. Bolting from a stoplight on Mercer, the Insight ably allowed me to out-drag and change lanes in front of a large, slow Chevy Suburban. (Sucker!) Certainly the engine(s) were taxed when grinding up Queen Anne, but downshifting to second meant no one was honking behind me. (Unlike the pronounced lag of a turbocharger, it’s less obvious when the electric motor lends a hand.)

Meanwhile, the Insight’s endlessly fascinating gauges monitor energy expenditure (ASST) and preservation (CHRG), creating a virtue meter feedback effect. Orange means you’re spending (bad) and green means you’re saving (good) when you coast, brake, or decelerate. Moreover, a little bar graph provides a constant, real-time estimate of your gas mileage (up to 150 mpg!)—further reinforcing responsible, cost- and conservation-minded driving habits. (However, my real-world, in-city driving yielded something like 48 mpg.)

But “How fast will it go?” was one of the most commonly asked questions about the Insight. Its digital speedometer easily nosed above 70 in I-5 traffic, but Montana was too far away for an honest pedal-to-the-metal top-end evaluation. Suffice it to say that it’s as fast as any small economy hatchback.

Economy, not performance, is what the Insight is about. That official 61 mpg figure for the city is also achieved by one remarkable yet unsettling feature. Possessed of two motors, the Insight actually turns off its internal combustion model at traffic lights and long bridge waits when in neutral. Every driver’s worst fear is seemingly realized as the tach drops to zero and a little blinking “Auto Stop” light comes on. Then, as the traffic signal turns to green, one puts the car into first and the gas engine miraculously returns to life—every time. (My Insight did stall once or twice after I overeagerly slammed it into first; again, it’s no drag racer.)

But what does the public think?

“I LIKE IT,” said a guy in-line skating along Alki Boulevard, although he expressed reservations about the car’s covered rear wheel-wells (for less aerodynamic drag—and hence, better mileage). His companion wasn’t so sure. “They gotta change the name,” she declared. “Kids aren’t gonna want a car called the ‘Insight.’ That’s a New Agey name.” (We personally recommend the alternate spelling Incite—which sounds a little more kick-ass.)

Another older onlooker didn’t like the futuristic, Jetsons-like design. “I hope it grows on you,” he chuckled. Told of the car’s fuel economy, he amended his position. “It looks a whole lot better now.”

At Green Lake, one observer commented, “It looks like a Citro뮮” Indeed, the Insight owes an obvious styling debt to that iconic French car of the ’60s and ’70s, and to Honda’s old Civic CRX model. Nobody approached the vehicle at the U District Dick’s, although several teen girls did point and giggle. (Then again, it may’ve been the driver they were ridiculing.) Tooling around Seattle, however, there were stares, smiles, and thumbs-ups aplenty. Young male drivers of souped-up Honda hatchbacks were particularly interested (natch), while the reaction of those at the helm of SUVs couldn’t be gauged—since their doors are at eye level to the Insight.

“It’s a great second car,” said one thoughtful young father at Golden Gardens. Still, he wondered, “Where do you put your baby?” Without a rear seat or storage capacity for more than a few grocery bags, the Insight can’t be used for hauling lumber, kids, or large rambunctious golden retrievers. “It’s a lifestyle thing,” he concluded, since progressive Seattle families can feel good about parking the Insight next to the low-mileage, pollution-spewing sport ute in the garage—using the one for pee-wee soccer practice, the other for routine errands and commuting.

NOT A HOT ROD or an SUV, can such a small, slick, but uncheap vehicle find a market in the US? Sure, according to one expert who sees a lot of cars pass through the Pink Elephant car wash where he works: “It’s nice, man! People will buy it.”

But will it get you chicks? In other words, if the macho, bulked-up SUV represents the idealized American self of our selfish, affluent age, where’s the sex appeal of being modest, sensitive, and environmentally correct? The Insight draws approving comments, but not lust—which is the essence of automotive marketing. It asks American drivers to accept less horsepower and forgo fantasies of off-road adventure. Yet for a particular class of green-minded Seattle motorists, its steep price—compared to, say, an $8,000 Daewoo—pays a certain moral-ecological dividend. Early adapters to hybrid gas-electric technology can feel smugly superior about saving the planet, even as they’re driving in the slow lane.