A FEW MONTHS AGO I was at the Crocodile, looking over a pack of heads at the Fastbacks’ Kurt Bloch as he bounced across the stage with his guitar. Then, all of a sudden, in the middle of a song, he just disappeared from view.

“The next thing you know,” he told me later, “I’m on the ground and my leg is just on fire. I look down and my kneecap is on the side.”

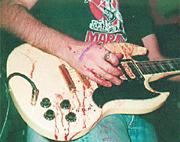

A blown knee is just one of the many injuries that can occur in a line of work that sometimes includes stage-diving, speaker-climbing, guitar-swinging, knee-sliding, and general jumping around. Bloch himself has suffered an array of calamities: a broken arm from on-stage pig-piling, chronic back pain from a heavy guitar, and a head injury that made the rest of one particular show look like the Texas Chainsaw Massacre. “I was covered in gore and my hair was matted down with blood,” he recalls.

His experience isn’t atypical.

Smashed heads, for example, are far more common among today’s rock musicians than smashed hotel TVs. The Presidents’ Chris Ballew seems to be going for the record. There’s the time he cracked his head on an overhang at the very end of a show—”As the last chord faded out,” he remembers, “nobody moved or said anything. Just shock and silence.” Then there’s the time he smashed his head against a monitor during an important show for music industry folk—”I thought it would be funny if I just kept playing these songs about kitties and bugs while I was dripping with blood.”

In spite of the obvious pain, nobody stops performing if he or she can help it. I’ve heard about musicians who kept playing with a fractured arm, with burning cigarette embers in an eye, with a split palm. Limping off stage in the middle of a set doesn’t seem to be an option. Maybe that’s why, despite the much-celebrated recklessness of rock, being injured is not part of the rocker image. The mystique tells us that only death stops them, nothing less. You may have seen a dozen minor rock injuries without knowing it, because the band played on.

Or maybe you’ve unknowingly cheered one on. Tad Hutchison still has the scars—and 15 stitches—from a Young Fresh Fellows gig. “I was standing on my drums,” he says, “dancing around like I was some kind of a smarty-boots, and then I started to fall forward. It was surreal because I could hear the crowd yell for joy as I fell, like they kind of wanted me to do it.”

Still, sometimes the show can’t go on. Murder City Devils bassist Derek Fudesco has taken his share of cuts and bruises in the line of duty, but when he crawled to the edge of the stage and saw his foot hanging by tendons—bent in the wrong direction—it was enough to bring down the curtain. It happened during a Devils show this past spring, in the middle of a song, when he jumped and slammed the back of his head on a steel beam. He was knocked out cold in mid-air, then broke his leg upon landing. “My leg just exploded,” Fudesco recalls. “The doctor said that since I was unconscious all my muscles were relaxed. That’s why it shattered like dropping a glass.”

A six-inch metal bar and a few bone-screws haven’t changed his resolve, however. The hardware will stay in for five years, but it will not make him more cautious. “This won’t change a thing,” he says.

IN ADDITION TO THESE kinds of on-the-spot injuries, musicians are subject to other maladies that develop over time. Many of these fall under the umbrella term “repetitive stress injury,” which refers to any problem that arises from doing something over and over again, like playing an instrument for hours a day. RSIs can affect various parts of the body, depending on the instrument, but the most familiar is carpal tunnel syndrome, a swelling and scarring of the nerves that run through the wrist. It causes pain and circulation problems, and it isn’t just for computer nerds anymore.

Leslie Hardy doesn’t wear a pocket protector, but she has such serious carpal tunnel syndrome that at times she has been unable even to wave to someone. Hardy has been playing keyboards and bass for nine years, most recently alongside Fudesco in the Murder City Devils. In the past two years her condition has flared up. It has recently been complemented by tendonitis in both shoulders, as well as back pain. Visits to the chiropractor used to be a weekly routine, but the success of her band has meant more activity and less treatment. She lifts weights and takes prescribed steroids for the carpal tunnel, but it’s hard to follow a routine that includes icing before and after gigs and wearing special wrist braces. “The doctor told me I should play in them, but they look so ridiculous that I just won’t do it,” Hardy says.

The alternative is surgery. If she does go under the knife, she’ll join a long list of other musicians, mostly drummers. They’re the most vulnerable to the unholy rock trinity of carpal tunnel, tendonitis, and back pain.

After years of playing with the Fastbacks, the Posies, and others, Mike Musburger is a first-rate drummer, but twisting around in a trap set has damaged his spine and the pain and swelling in his wrists sometimes make his hands go numb during a show; even simple things such as holding a pencil or a phone are difficult. He goes to a massage therapist once a month and makes trips to the chiropractor three times a week. “If I didn’t do that stuff I’d be a wreck,” he says. “I couldn’t get out of bed in the morning.”

His massage therapist, David Gibson, has treated dozens of rockers like Musburger and has even been hired on to tour with Pearl Jam. There’s a whole culture of therapists—kept behind the scenes, of course—who travel with musicians who can afford to take them. As Gibson puts it, “We see our rock gods leading these anarchic lives, pouring everything out onstage, partying and all that, but we don’t want to see them getting acupuncture.” Both professional musicians and athletes make a living with their bodies, he observes, but where football and baseball players focus on the physical, musicians concentrate on creative expression, neglecting their bodies until they need more than just a stiff drink to bounce back. When a Seahawks tackle strains a muscle, he ices it up, sits in a whirlpool, and gets worked over by a trainer. When a young, up-and-coming rocker strums his wrist into oblivion, the response is usually aspirin, booze, and the kind of drugs you can’t get at Bartell.

PETE TOWNSHEND famously switched to acoustic guitar in the ’90s because of hearing loss—which is a whole subject in itself when it comes to musicians—but younger artists have a harder time giving up THE ROCK. “I’m not done with that visceral feeling of playing loud rock drums,” Musburger says.

Unfortunately for Musburger and his ilk, this type of dedication doesn’t always pay off. It’s becoming something of an old saw that musicians are shut out of the health insurance system. Even for those signed to a major record label, there’s still no coverage, or even a company rate. The Fastbacks’ Bloch describes the predicament: “They lend you the money to make the record, they own the record, they give you maybe 15 percent of what they make off it, and then you’re not covered by the same company policies that the rest of the people who work there are. Does that make sense?”

Next time he’s playing a solo on a blood-splattered guitar, Bloch would like some reassurance that he’ll be able to pay his medical bills. So he’s got a proposition: “We’ll tell the insurance companies that the Fastbacks will wear their name on stage if they cover us.”