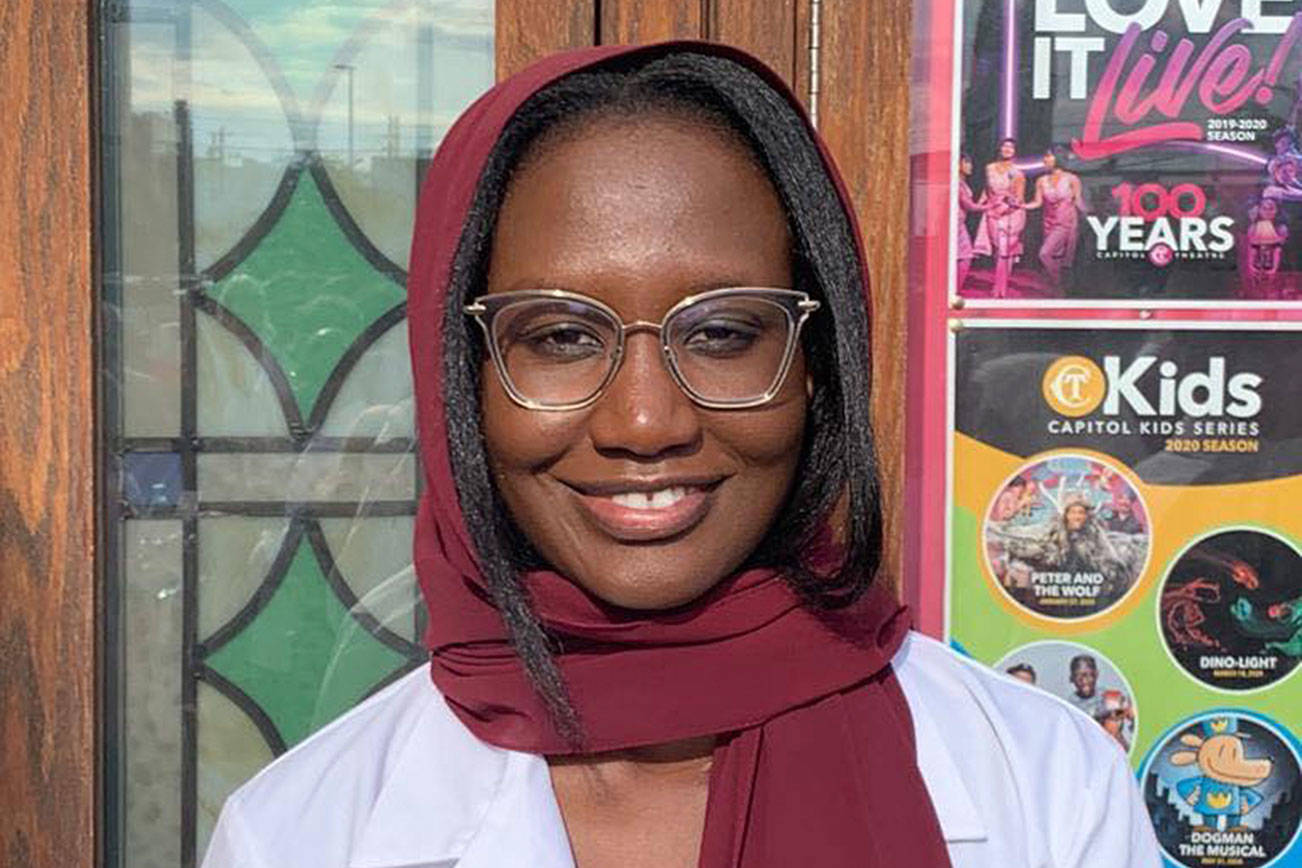

When Amineta Sy arrived in the United States in 2016, she did so with a bachelor’s degree in biology under her belt.

Sy, who is originally from the northwestern African country of Mauritania, had earned that degree at university in Morocco with the intention of going into medicine. But when she immigrated to this country, the Bothell resident had to take a few steps back before advancing her education.

Some of those steps backward included enrolling in English as a second language (ESL) classes at Cascadia College in Bothell.

“It was mostly frustrating,” Sy said. This was because there were a couple courses she had to retake in order for medical schools to recognize her degree, adding that she had the scientific knowledge — just not in English. “It wasn’t easy at all.”

Sy enrolled in her first ESL class about a month after her arrival. Within nine months, she retook the courses and earned the credits she needed to take the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT).

She now attends Pacific Northwest University of Health Sciences in Yakima and is currently interested in specializing in neurosurgery but said she is open to other fields of medicine.

Now. Let’s just take a step back real quick.

The MCAT and getting into medical school is difficult enough, but can you imagine doing all this in a language that is not your first language? And having to fill out all those applications and go through all the red tape?

“The system is not easy for people like us,” Sy said about immigrants.

Let’s be real. The system is not easy for people in general. So when Sy was detailing her journey to me, I was suitably impressed.

Learning from difference

While she was at Cascadia, Sy said her ESL classmates were a diverse group, though most were there just to learn English. She said there were two others who were seeking higher education.

Dave Dorratcague, who teaches ESL at Cascadia, said the demographics of the students in his classes are never homogeneous, ranging from people in their late teens to people in their 70s. He has taught people who have doctorate degrees as well as people whose education stopped in elementary school.

The ESL classes come in five levels, with level one being pre-literacy and level five including listening, speaking, reading, writing and grammar skills. Dorratcague’s classes are specific to immigrants and refugees. Cascadia also offers ESL classes for international students who are taking college credit courses at the school.

Dorratcague said people’s goals for learning English vary as well. There are those like Sy who are working to further their education as well as people who want to start their own businesses, help their children with their schoolwork or just improve their general proficiency.

He said this variety enhances the classes.

“Everyone has something to offer,” Dorratcague said. “Everyone can learn from someone else.”

And in terms of people’s home countries, they’re from “pretty much everywhere,” he said, adding that the demographics ebb and flow depending on the geopolitical situations around the world.

Dorratcague leverages people’s differences in class. For example, he said for a writing assignment, he might ask students to talk about a holiday they celebrate in their home country or describe certain traditions that may be different from traditions here in the United States. The students are the experts on their culture so this works in their favor.

I witnessed this in action firsthand growing up. At one point, my mother attended ESL classes at Edmonds Community College. She brought me with her as my father would be somewhere with my sister and I was too young to stay home by myself.

Like the Cascadia students, my mother’s classmates were adults of all ages and came from all over the world and I remember learning about bits and pieces of everyone’s home countries.

‘Without English, nothing’

Like Sy, Ana Louisa Leon came to the United States with a specialized professional background.

She had worked as an industrial engineer in Venezuela.

Leon, a Lynnwood resident who took ESL at Cascadia, said immigrants often have to start from zero when they arrive in the United States.

Because pretty much any job requires you to know English.

“Without English, nothing,” Leon said about job opportunities.

Her plan was to study and improve her English so she could continue working in her profession.

She and her husband brought their family to this country for a better quality of life for their children. Leon said they left a dangerous political situation in Venezuela and had applied for political asylum to be able to stay in the country. Unfortunately, they learned the week of Oct. 7 that their application was denied and they will have to return to Venezuela later this month.

Although they will be moving back home soon, Leon said she is thankful for the ESL classes as they helped her improve her English skills. Back home, she studied English and used it in her professional life when she worked with American companies.

Practice creates confidence

Karla Monica Loyola, a Kirkland resident who attends Bellevue College, was in the IT field in her home country of Peru, working her way up in the industry to become a project manager.

She came to the United States four years ago, initially living in California where she had family. Before moving up to Washington in 2018, she took ESL classes at a local college in the Oakland area of the Golden State.

At Bellevue, she is in her first quarter studying network services and computing systems with a concentration in cloud architecture and services.

For Loyola, the key to her gaining confidence in her language skills has been practice. She said when she was in California, she and her family would speak Spanish at home. It wasn’t until she moved up to Washington with her boyfriend — who doesn’t speak Spanish — that she has been able to practice the language on a regular basis.

And now she feels more comfortable holding a conversation in English and does not panic whenever the phone rings.

Sy said it’s easy to become introverted if you don’t speak English and it’s important for immigrants — especially if they are working toward advancing their education and career — to step out of their comfort zones.

And just because you do step out, doesn’t make things any easier.

Sy said as a black immigrant woman who is also a Muslim, that puts her in the minority at school. She often worries about her accent being too strong but realizes she isn’t the first person and won’t be the last person who speaks English with an accent. Sy also thinks about the reverse situation — how a native English speaker learning a second language would also have an accent in that second language.

She’s got a point.

How many of us have learned a foreign language in school (or elsewhere) and just butchered it? And how many of us would be confident enough to pursue a professional career speaking mostly that second language?

Windows and Mirrors is a bimonthly column focused on telling the stories of people whose voices are not often heard. If you have something you want to say, contact editor Samantha Pak at spak@soundpublishing.com.