Following the deadly protest in Charlottesville, Va., on August 12, the daughter of a former Kent Police chief knew it was only a matter of time before people started asking questions about her father.

That protest, which was attended by white nationalist groups and resulted in the death of an anti-racist activist and the injury of 19 others, was triggered by the impending removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. A national conversation about the suitability of such memorials has since ensued, resulting in the quick removal of Confederate statues in numerous locales. That debate has extended to Seattle as well, where Mayor Ed Murray has called on the proprietors of Lake View Cemetery to remove a memorial to Confederate soldiers there.

So it was only natural that Kent’s Robert E. Lee Memorial Building would come into question. The city had a ready response to those who would like to see the removal of the large letters on the west side of the City of Kent Police Department at 221 Fourth Avenue South. The Robert E. Lee memorialized in Kent is no traitor; though he was named after one.

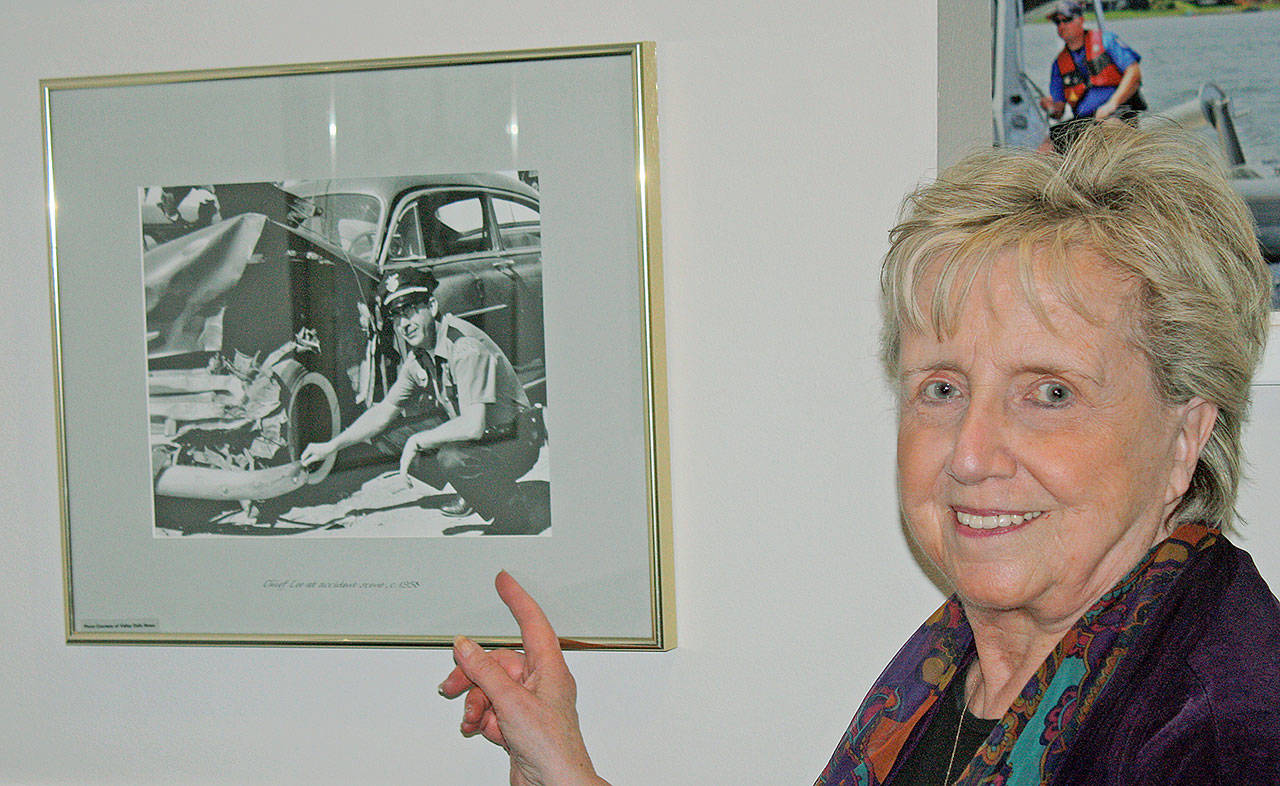

“Oh my gosh, I figured they’d get a million inquiries about my dad,” says Vicki (Lee) Schmitz, the daughter of the man who led the police force for 18 years, from 1948 to 1966.

While it did not receive quite that much attention, there was some concern expressed over the name. Enough that Mayor Suzette Cooke chose to talk about the former police chief during her August 15 report before the Kent City Council. She said she was responding to a comment on the Kent Police Facebook page asking what the department was planning to do about the name on its building following the events in Charlottesville.

“Considering the fact the most recent activities that have gone on over a certain Robert E. Lee statue, I thought I would bring to your attention to our own Robert E. Lee with whom we have a great pride in what he accomplished in this city,” Cooke said to the council.

The police headquarters were dedicated on Sept. 18, 1992, in memory of Lee, who died in 1985.

“Chief Lee was highly regarded in this community for both civic and law enforcement leadership roles,” Cooke said. “It is an honor that our Kent police headquarters are named in his memory.”

Responding to a request for comment, Schmitz, of West Seattle, was eager to share her father’s story. She says she wants people to know about the Robert E. Lee the police headquarters is named after.

Lee was born in 1911 in Kentucky to George and Alice Estes Lee, who died during the birth. He was named Robert Edward Lee after the general, says Schmitz, adding that doing so was a common practice at the time. Indeed, the popularity of the Confederacy was at a peak in the year that the future police chief was christened, despite the fact that it had been 46 years since the secessionists lost the Civil War and with it the fight for slavery. In the midst of racist Jim Crow laws and following the establishment of the NAACP a couple years earlier, 1911 saw the largest spike in the creation of Confederate monuments and memorial sites in the nation’s history, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

George Lee eventually moved his family to Montana, says Schmitz. Robert E. Lee grew up there, leaving in 1929 to join the U.S. Navy at age 18. He decided to live in Seattle after his four years of service. He married Ann Ellen Sund and they had two children, Vicki and Robert E. Lee Jr.

“It was 1933 in the middle of the Great Depression,” Schmitz says about her parents settling in Seattle. “My dad sold books and did odd jobs.”

In the late 1930s, Lee went to work for the King County Sheriff’s Office and moved his way up to chief of detectives. The City of Kent recruited Lee in 1948 to be its police chief.

“He was the most honorable man ever and one of the most respected men,” Schmitz says about her father.

Kent Police had only five officers when Lee took over as chief in the town of about 3,000 people. The force had 15 officers and three clerks when he retired.

“He put professional standards in place,” Schmitz said. “He only hired university grads, even though he didn’t have a degree.”

When Lee told the council he planned to retire to go into private work, City Attorney John Bereiter described what Lee had accomplished.

“I have had the opportunity to compare Kent’s police department with the others, and I have never found one to match Chief Lee’s,” Bereiter said, according to a 1966 edition of the Kent Independent newspaper.

Lee remained in Kent after he retired. He was a City Council member from 1968 to 1972 and worked for Mannesmann Tally, a Kent manufacturer of computer printers.

Cooke met Lee in 1981 when she was hired as the Kent Chamber of Commerce executive director.

“Bob, as we called him, was the commissioned membership salesperson for the Kent Chamber of Commerce,” Cooke said. “The Kent Chamber of Commerce Robert E. Lee Membership Development Award is given each year in his honor.”

Lee also served as the Kent School District hearing officer, and founded the Kent Juvenile Court Committee, Cooke said. His community service garnered him an award from the Kent Rotary Club.

Schmitz, who worked five years as a Port of Seattle planner and 20 years as a King County administrator, says that she would like to see some changes made to the building that bears her father’s name. She says she wishes the City of Kent had put “Chief” in front of her dad’s name on the building to distinguish him from the general. She also likes the idea of adding a plaque on the side of the building to inform people about her dad. She is scheduled to give a presentation about her father at the Sept. 19 meeting of the Kent City Council.

news@seattleweekly.com

A version of this story originally appeared in the Kent Reporter.