On a Tuesday evening last May, federal inmate Bianca Bowler watched as one-legged Roxanna Brown, wearing a shirt and towel and supporting herself with a plastic chair, inched along toward the women’s shower room at the Federal Detention Center in SeaTac. Arrested in connection with antiquities smuggling and wire fraud, and being detained for transfer from Seattle to face a judge in Los Angeles, the petite, 5-foot-1 Brown had been suffering from nausea and diarrhea for most of four days, and badly needed to bathe.

Brown slid the chair like a walker as she moved across the floor of the hulking eight-story prison. Then, as inmates remember it, she stumbled and fell in front of a corrections officer.

“The officer watched this happen and simply gave her dirty looks,” Bowler recalls. She and another inmate came to Brown’s aid, Bowler says, lifting the respected scholar and dragging her into the showers. They were worried about her survival, Bowler says.

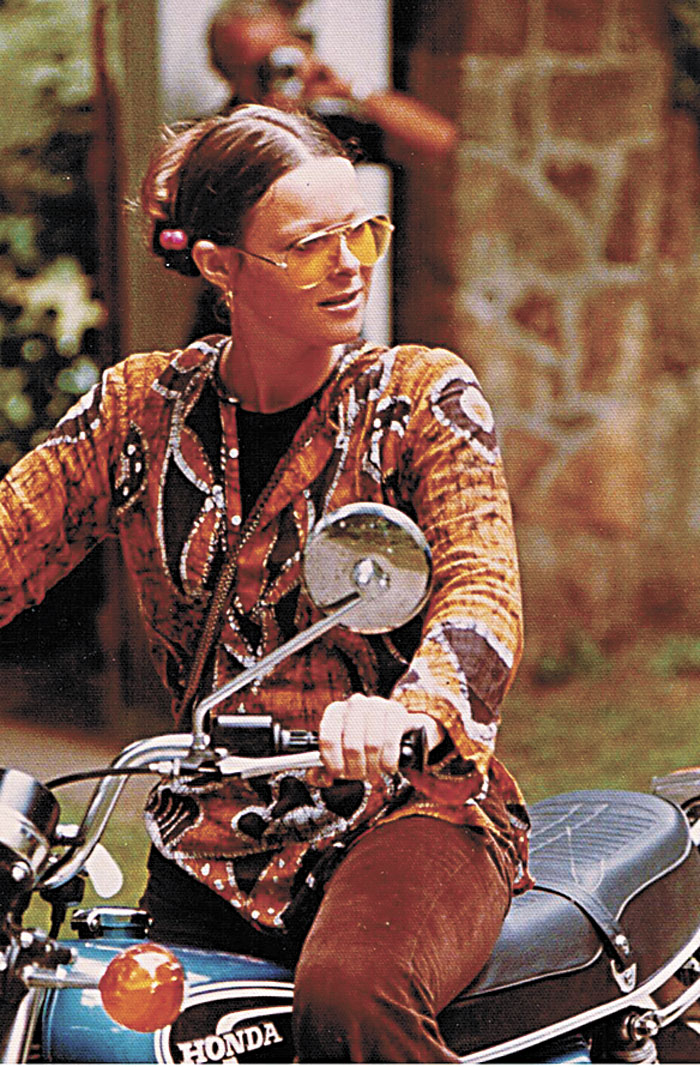

At least someone was. Brown was brought into the detention center on one leg and five days later carried out foot first. The American-born, Bangkok-based museum director had survived Vietnam as a war correspondent, hanging with the likes of David Halberstam and Ted Koppel, and had been close to death after losing her right leg in the wake of a motorbike crash in Thailand in the ’80s. But it was from a modern American prison that the globetrotting Southeast Asian art historian would emerge in a body bag on May 14, 2008. Twelve days earlier, she had turned 62.

In dire need of emergency care, Brown died about seven hours after inmates say she collapsed in front of the officer. Inmates say they, not the detention center staff, went to her aid in her final hours—they had to support Brown’s head the way you “support an infant’s,” Bowler says, to feed her antacid. Federal officials dispute the prisoners’ versions, and contend that Brown, who was apparently the first inmate known to die unexpectedly at the 10-year-old detention center, had showed initial signs only of a minor gastrointestinal “bug.”

But all agree that the adventurous woman who skirted death in the Third World was killed in the First World by a perforated gastric ulcer known as peritonitis. “It’s surprising,” says Brown family attorney Tim Ford of Seattle, “that anyone in a country with such access to medical care dies from an ulcer.”

The King County Medical Examiner ruled the death “natural.” Ford calls it negligence.

“They [detention staff] did basically nothing to help her,” he says. In July, Ford filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Seattle against the Federal Bureau of Prisons for alleged violation of Brown’s civil rights. The suit asks for unspecified money damages on behalf of Brown’s son, Jaime Ngerntongdee of Bangkok.

In documents filed in the case last week, retired King County Medical Examiner Donald Reay, now a legal consultant, says his review of Brown’s autopsy report indicates her peritonitis existed and began progressing “probably 24 to 36 hours, no less than 12 hours” before her death. “She likely would have appeared very ill and in great pain,” with intestinal fluids leaking through a perforation into her abdomen, “and she probably would have been unable to tolerate palpation [exam by touch] of her abdomen during this time.” Such a condition required emergency treatment, Reay concludes.

Brown’s family thinks she shouldn’t have been in the 500-bed detention center south of SeaTac Airport in the first place. Federal prosecutors “obviously took something to a grand jury that was sitting around on a Friday afternoon, and returned the world’s vaguest indictment,” says attorney Ford. The one-paragraph document issued by a Los Angeles grand jury accuses her of aiding and abetting a scheme to defraud the IRS. It claims she allowed her electronic signature to be used on appraisal forms with inflated, tax-deductible valuations. The continuing probe, centered in Los Angeles, involves a group of antiquities dealers and wealthy donors who trade in ancient ceramics, stone, glass, and brass.

Brown had cooperated with federal agents as they developed their case over five years, helping them identify suspects and providing information. Court records show she opposed removing valued objects from their homeland, and said that if her signature had shown up on fraudulent documents, it was without her knowledge.

But she became a suspect when additional evidence surfaced early this year. In a series of January raids, agents found an e-mail she’d sent to a gallery operator suspected of defrauding the IRS. He’d asked her to sign and fax blank appraisal forms he could fill out later. In her message, Brown said she was “delighted to be [the gallery operator’s] partner in this.”

That didn’t necessarily mean she was a knowing partner in crime, says her family. But on May 9 agents swooped into her Seattle hotel room, where she was waiting to speak the next day at a University of Washington academic conference. Brown made contradictory statements to agents, they say, though she held to her story that others misused her signature, according to a federal court affidavit.

Once the government’s confidant, Brown became—and remains—the only person charged in the fraud probe, says Thom Mrozek, spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney’s office in Los Angeles. Without her, the feds appear to have a weaker case against other suspects. In court, prosecutors called her death “tragic.”

“What makes this even more tragic,” says her brother Fred Leo Brown of Chicago, “is that between Roxanna, my mother [now 92], and I, we have done so much for this country.” Wounded in Vietnam, Fred Brown is a writer and performer who travels around the U.S. presenting a morality play called The Lessons of War.

The Browns were “the all-American patriotic family,” he says. “And this is howour country repays us?”

Roxanna Maude Brown’s intrepid life unspooled over six decades, from the American Midwest to the Asian Southeast, before it ended abruptly in Seattle.

She grew up on an Illinois chicken farm; her family branded the finished product as Brown’s Fried Chicken, which is still around today, says Fred. A high-school cheerleader and senior class president, she went on to study journalism at Columbia University in New York and graduate with a degree in philosophy. At 21 she rode cross-country on a motorcycle to California, from where in 1968 she headed to Australia, then to Vietnam to see her brother.

“She just found Asia amazing, exactly what she’d been looking for her whole life,” says Fred, who became an Army sergeant. “She told me she felt that in another lifetime she must have lived there.”

Bilingual and a budding writer, Roxanna wrangled freelance reporting jobs during the Vietnam War, working at times for the Associated Press; Fred Brown says she was offered an AP bureau job in Phnom Penh, but turned it down. Besides reporter/author Halberstam and TV journalist Koppel, for whom she served as a French interpreter, she was mentored by AP reporter Peter Arnett and actor/photojournalist Sean Flynn, son of swashbuckling movie star Errol Flynn. Sean Flynn, along with John Steinbeck IV, namesake son of the author, operated the Dispatch News Service, which issued Seymour Hersh’s groundbreaking My Lai massacre exposé.

The dashing Flynn and the sweet-faced Brown, a teenage Miss Illinois finalist, also had a romance going, says her brother. “She and Flynn spent the night together in Cambodia on April 5, 1970,” Fred says. “The next morning he was captured.” Flynn was later presumed killed by the Khmer Rouge.

Brown ultimately decided she couldn’t make a living freelancing, says her brother. His photo collection and several YouTube videos on recount his sister’s Southeast Asia life in installments, ascending from the cute 20-something in a Department of Defense press-card photo to the mysterious woman in shades and a bamboo sun hat who scoured rice paddies for ceramic remnants. Roxanna found Asia the gateway to her future and the world’s past: By 1975, after witnessing the fall of Saigon, she moved to Singapore, studying Asian art and antiquities, eventually earning her master’s in Asian art at the University of London.

Subsequently, she produced the first of seven books she would author or co-write, and edited an arts magazine in Hong Kong. But while living there, she became addicted to opium, and was eventually arrested, detained, and ordered to leave the country. She soon went off to Thailand, laboring to kick her habit and return to her studies, says her brother.

She ended up marrying a former Buddhist monk, with whom she had a son. In 1982, when Brown was 36, she was riding her silver and red motorbike on the congested Bangkok streets when she was hit by a truck, eventually losing her leg. “The truck ran her over and was backing up to finish her off,” says Fred, “when bystanders stopped the driver”—who apparently thought he could lessen his blame by eliminating Brown as a witness.

“A surgeon on lunch break happened by, and, taking a knife, cut her open and stopped the bleeding of a main artery,” adds Fred. “She was probably about 60 seconds away from death.”

She spent six months in a hospital, with her Illinois mother at her side. Brown later flew to Chicago and went through almost three years of rehab, says Fred. Her recovery “left her feeling she had experienced a miracle,” he says.

Roxanna’s marriage ended, but she trudged on, a one-legged single mom who, upon returning to Bangkok, ran a small bar and worked part-time as a ceramics teacher. She got around by wheelchair or prosthesis and cane. After 2000, she returned to the U.S., where, aided by friends, she enrolled in grad school at UCLA. She left with a doctorate in 2004, at age 58, having become an expert on the recovery of ceramics from historic shipwrecks.

Brown regularly produced scholarly articles on Asian plate and vase production around the 15th century, and was best known for her book The Ceramics of South-East Asia: Their Dating and Identification. She lectured often on the “Ming gap,” delving into the economics of ceramic trade cycles during the Ming dynasty.

By 2005, she returned to Thailand and became an advisor to Surat Osathanugrah, founder of Bangkok University. He later appointed her director of the Southeast Asian Ceramics Museum at the university’s Rangsit campus, where she oversaw a collection that included 2,500 ancient ceramics.

All was good. But in contrast to her open book of a life, the story surrounding Brown’s death is as murky as the truth about her alleged crime.

This past January, federal agents raided museums in Los Angeles and San Diego, seeking evidence of a long-suspected southern California smuggling scheme. The case involved antiquities from China, Burma, and Thailand, dating back millennia to the Ban Chiang culture. Though the scheme has been only sketchily outlined by the feds, agents suspected some objects had been looted from Asia and smuggled in clandestinely, or represented to customs inspectors as replicas when in fact they were valuable originals.

Many were small objects— ceramic remnants, for example—passed around by a loose-knit group of collectors and dealers. Some were donated to museums at inflated valuations, the feds believe. An object worth $1,000, for example, could be bumped up in value to $5,000 through a dishonest appraisal, handing the donor a larger tax write-off.

The case grew out of an undercover investigation by the National Parks Service, which probes artifact thefts. Among those named in court papers was Jonathan Markell, co-owner with wife Cari of L.A.’s Silk Roads Gallery, who both decline to comment. Los Angeles U.S. Attorney Thomas P. O’Brien claimed the couple “used Brown’s electronic signature on several occasions to falsify appraisal forms.”

Brown was portrayed by the feds as an expert whose signature had been misappropriated. When Fred met Roxanna for lunch in California, he says she seemed tired and pale, her eyelashes weighted with mascara. Roxanna told Fred the government had begun investigating her, he recalls.

“She said she’d already talked to the FBI and that was good enough, there shouldn’t be any problem,” Fred says. “But they might continue to do something, and they could ruin her reputation, and there was nothing she could do to stop them. It broke her heart.”

The investigation pushed on. The feds found new documents during the January raids that caused them to believe that Brown not only was in on the fraud scheme but had herself smuggled Burmese art into the U.S. They claimed there was evidence that six years earlier she had sold some antiquities to a man investigators believe was a smuggler. Additionally, gallery owner Markell had asked Brown in 2007 to sign a half-dozen blank appraisal forms for his future use. Markell, in an e-mail, “stated that he would be sending her $300 for using her, ‘as it were’, as the appraiser,” since, due to recent federal rule changes, he couldn’t sign an appraisal himself.

“If you are nervous about doing this,” he wrote, “please realize that Republicans are still in office, the IRS does not have enough personnel to review small-time appraisals, and the appraisals are very well written and will never be challenged even if they do.”

“No problem!” Brown responded. “I am delighted to be your partner in this.”

The feds suspected Brown knew Markell allegedly inflated his valuations, thus lending her signature made her party to the scam. Brown’s family says she was just doing a favor for the Markells, who were friends and who even witnessed Brown’s 2001 will, according to records in King County Superior Court. (The will is now in probate. No value is given for Brown’s estate, but her brother says she was poor.)

In May, on the day Brown arrived in Seattle for the academic conference, a grand jury in Los Angeles had secretly indicted her on a charge of wire fraud, related to the faxing of her signature that allegedly enabled the scheme, punishable by up to 20 years in prison. Fred Brown thinks she was being squeezed by prosecutors: “I believe they wanted her to rat out everyone,” he opines.

In her room at the University District’s Watertown Hotel, Brown was confronted by agents from the IRS, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the Parks Service. Federal tax agent Bonny MacKenzie says in an affidavit that Brown contradicted herself at times during the meeting, and couldn’t remember details about certain sales, mostly those from 2004 and earlier. But Brown said she did not believe any of the appraisals in question were overvalued, and she approved of donations because the objects went to museums.

That was pretty much what she told her brother during their California lunch, Fred says. She conceded that providing her signature up front was like a blank check, but the case revolved around the appraisals. “And she said that, like in real estate, they’re subjective,” Fred recalls.

Not to the feds: They told her she was being arrested that day in Seattle. They didn’t cuff her; she needed a hand free to use her cane.

Brought to the detention center on a Friday after the courts had closed, Brown faced a long weekend. “Just by looking at her” when she was brought in, said Bianca Bowler, who was finishing up a sentence for ID theft, “you could tell that she was unwell. She was doubled over with terrible stomach pain and asking for medical help.”

Bowler, according to the Brown family lawsuit, wrote down her recollections of Brown’s confinement on May 24, 10 days after her death. By then, assistant federal public defender Mike Filipovic had begun picking up on what he termed “disturbing reports” about Brown’s death. In an e-mail to the Bureau of Prisons, Filipovic said he’d heard that Brown, just before she died, had tried to get medical attention from her cell for more than two hours, “and that cries and banging were either ignored by staff [or] she was told to wait until the morning…It seems to me that an investigation from an agency outside the building is what should be conducted.”

The Bureau of Prisons is not commenting in light of the Brown lawsuit, and has not responded to a Seattle Weekly Freedom of Information request made in August, seeking documents from any investigation. But the U.S. Attorney’s office in Seattle is attempting to have the lawsuit dismissed for lack of proof of any “deliberate indifference” to Brown’s condition, which must be shown if the government is to be held liable. Brown family attorney Ford is challenging the motion, arguing the government’s version of events is not backed by the record.

According to a detention center health screening form, filled out when Brown was booked May 9, she appeared normal, alert, and oriented. She was also depressed, and her prosthesis was causing some pain. Brown was given an antidepressant, acetaminophen, and simvastatin, which she apparently had been taking to control her cholesterol level.

Inmate Bowler says Brown, housed in a cell next to hers, “just seemed to get worse and worse.” Come Monday, she was too sick to make it to court. A medical record from that day states she was suffering from nausea and vomiting, but suggests the ailments began on Monday morning rather than over the weekend. The record notes that Brown “claims” she went to the bathroom “8–10 times since this morning.”

A medical officer, with a clinic doctor’s approval, concluded she was suffering from gastroenteritis, a stomach or intestinal inflammation. He gave her an injection of promethazine to control vomiting and prescribed loperamide capsules for diarrhea symptoms.

The record indicates a touch test was done on her abdomen. It concluded: “Tenderness on palpation (no).”

On Tuesday the still-ailing Brown made a brief appearance in court, seated in a wheelchair. A magistrate set over the detention hearing for the next day to determine if, once Brown arrived in Los Angeles, she might be released under certain conditions. That evening, around 7 p.m., Brown, weakened further, fell on her way to the shower, according to inmates. Bowler and another prisoner helped her to a stall, “even having to turn the water on for her because she was so weak from her pain,” Bowler recalls.

The corrections officer, Priscilla Vaughn, denies she snubbed Brown prior to the shower. A Sept. 30 affidavit, presented by the government in its dismissal motion, gives no indication Brown fell at all. Vaughn merely saw Brown “hopping” along, and two inmates “helped guide” her to the shower, then back to her cell, Vaughn says. The officer says she knew Brown was sick—she had helped her get a clinic appointment the day before, she says—but did not speak with Brown after the visit.

Another inmate, Briana Waters, who in June would be sentenced to six years for her lookout role in the 2001 eco-terror arson of the University of Washington Center for Urban Horticulture, recalled in a statement that she had reported Brown’s deterioration to Officer Vaughn that evening, and was told the clinic would be informed. Vaughn claims she contacted the medical department, and a technician said she would call another medical officer at home. Vaughn also claims she checked on Brown around 8:20 p.m. and found her sleeping. Later the technician dropped off two pink bismuth tablets to combat an upset stomach, telling Vaughn they weren’t needed unless Brown woke up. Vaughn left the pills for her replacement officer and went home at 10 p.m., she says.

Meanwhile, inmate Bowler says she fed Brown some Maalox while another inmate supported Brown’s head. They also gave her water and ibuprofen, Bowler says, to help her sleep. At 10 p.m., the prison was locked down.

Around midnight, inmates heard Brown intermittently pounding on her door. A graveyard-shift officer appeared, Waters recalls. She says she heard the officer telling Brown, “Why are you on the floor…Get off the floor…Wait until the morning…I can’t open the door.” Another inmate, Sharon Carter, being held on drug charges, heard similar words, she says. So did Bowler, but she says the officer sounded “caring and concerned,” and did slip the pink bismuth under Brown’s door, telling her to go back to bed. It’s unclear whether Brown was able to get back into bed.

Sometime after 2 a.m. on Wednesday, May 14, Bowler was roused by a clamor outside her door. She got up and peered through a window. “The ambulance guys are here,” Bowler recalls thinking, referring to SeaTac Fire Department paramedics outside her door, gathered around with their rubber gloves. They had been summoned to perform emergency resuscitation, to no avail. Brown, Bowler says, was “on the floor, with her eyes open, but clearly dead.”

Nine days later, U.S. Attorney Tom O’Brien dropped all charges. “Defendant took ill with an apparent gastrointestinal bug on May 12,” his office soberly reported in a dismissal notice. “Defendant received medical treatment for her illness while in federal custody during the morning of May 13,” but “as a result of an undiagnosed perforated gastric ulcer, defendant died in custody.”

Brown family attorney Ford still shakes his head at that comparatively mundane conclusion to a life so audacious. “If only Roxanne had been in her part of the world, rather than in Seattle,” he says, “she might be alive today.”

As for the investigation that led to her demise? “It’s ongoing,” says O’Brien’s spokesperson, Thom Mrozek. “That’s all I can tell you.”