Three voicemails were waiting for me when I walked into my Seattle Weekly office last Wednesday morning. I already knew who it was and what they wanted. And I knew that they would keep coming throughout the day.

On the bus I had read the breaking news: 12 people killed at a weekly newspaper in Paris, apparently in response to the paper’s satirical depictions of the Muslim prophet Muhammad on its covers and in its pages. The gunmen were still at large. As the news unfolded half a world away, the U.S. media was on the hunt for a domestic angle to the horror, which is what led them to Seattle Weekly and to my voicemail.

They were calling because four years ago Seattle Weekly counted among its contributors a woman named Molly Norris, a cartoonist whose quirky jabs at the modern world could be found in this paper every week and who would, for a few months in 2010, become the flashpoint for the media’s clash with radical Islam.

Seattle Weekly was Norris’ best-known platform then, but not her only one. She also contributed regularly to City Arts, a monthly magazine here in Seattle where I served as executive editor during her time in the public eye.

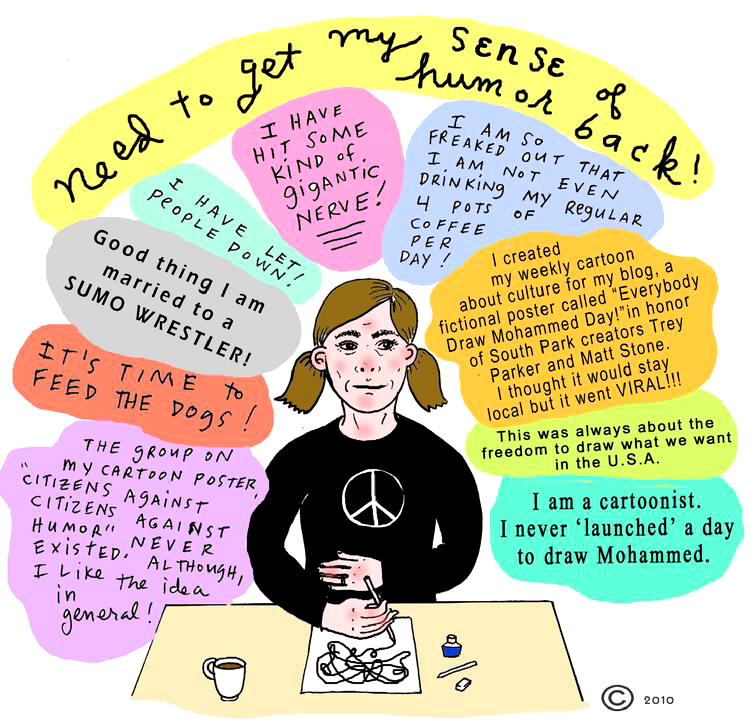

She also published comics on her website. It was there that the trouble started. Finding inspiration in the news of the week, she would often dash off a humorous drawing—replete with bright colors, thick dark lines, and off-kilter type—and post it, expecting little more than some feedback, maybe a commission, perhaps a share. In the spring of 2010 she was inspired by Comedy Central’s decision to censor an episode of South Park for fear that the show’s depictions of the Prophet Muhammad would ignite a religious shitstorm. Seeing an injustice, Norris summoned her powers of adorable antagonism and drew up a poster declaring May 20 “Everybody Draw Mohammad Day.”

Then she became the center of the shitstorm.

The comic went viral. Supporters sharpened their pencils while detractors sharpened their knives. Facebook pages decrying her depiction of the Muslim prophet—forbidden by some Islamic texts—popped up, and on May 19 a high court in Pakistan blocked Facebook, perhaps in fear that “Everybody Draw Mohammad Day” would take off. The social-networking site remained offline in that country for two weeks. By that point, Norris had called off the day of drawing.

“I didn’t mean for my satirical poster to be taken seriously,” Norris told City Arts’ Tim Appelo in mid-June 2010. “It became kind of an excuse for people to hate or be mean-spirited. I’m not mean-spirited.”

Norris’ intentions didn’t matter. On July 12, it was revealed that the comic artist had been the subject of a fatwa. According to his own interpretation of Islamic law, Yemeni-American cleric Anwar al-Awlaki told a magazine for radical Muslims, Norris’ “proper abode is hellfire.” I remember talking to Norris then. I remember her being scared. I was scared too. But we moved forward, continuing to publish Molly’s comics—as did Seattle Weekly—until September, when Norris disappeared.

The FBI called it “going ghost.” On their advice, Norris gave up her name, her home, her job, and her friends. No one here at Seattle Weekly or at City Arts has heard from her since.

Norris also gave up her narrative. And so we have seen her cause picked up by right-wing pundits like Larry Kelley, the author of Lessons From Fallen Civilizations: Can a Bankrupt America Survive the Current Islamic Threat? Following Norris’ disappearance, Kelley started the Free Molly Norris Foundation to draw attention to Norris’ plight as the first American to be driven into hiding by radical Islam and to raise money for her—though he has yet to find a means to get the money to Norris. In the days since the Charlie Hebdo attacks, Kelley—who had no prior relationship with Norris—has made numerous media appearances to talk about the cartoonist-at-large.

“We are no longer a free country if journalists can’t criticize a religion that, for example, believes apostates need to be killed,” he told Fox News, chastising the government for not providing Norris with financial support.

It’s difficult to argue with that, and to his credit, I agree with Kelley that the FBI should have given Norris more help. Yet I find myself unwilling to jump on board with Kelley or his fellow travelers who are in a rush to indict the entirety of the Islamic faith.

I believe everyone should be allowed to speak freely, and I expect the governments of this world to defend that right by prosecuting those who would threaten it. But I am also concerned about the gulf between the Muslim and non-Muslim worlds that appears to be widening as calls for freedom of speech become blurred with hateful speech that aims to denigrate the beliefs of a billion and a half people—the vast majority of whom are peaceful.

Given the choice between a world intolerant of certain images and another intolerant of certain beliefs, I choose neither. And in this moment, that’s a complicated stance to hold.

So what to tell all those news outlets searching for a soundbite?

Perhaps at this moment of great upheaval, tremendous sadness, and understandable anger, it is best to refer back to Molly Norris.

“Artists have to be not afraid when they create,” she told City Arts back in 2010. “You have to be responsible too with your freedom. It’s such a fine line.”

mbaumgarten@seattleweekly.com

This story has been edited from its original form for reasons of clarity.