There seems to be a single basic question being asked in Olympia this week about the Washington Department of Corrections’ early-release bungle: Who should get fired, or, in the case of Gov. Jay Inslee, voted out of office?

So far we’ve been told that the technical error that resulted in roughly 3,200 of the state’s inmates being released an average of 55 days early began back in 2002. But it came to the DOC’s attention only in 2012, and, by the administration’s telling, to the attention of Inslee in December, when he promptly made it public.

At least two major crimes occurred on dates when their suspects should have been behind bars: In November, an ex-convict driving under the influence in Bellevue allegedly crashed his car and killed his passenger; he was supposed to have been in prison until December 6. Last May, another man shot and killed a teenager within two weeks of his release; he was supposed to have been in prison until August 10.

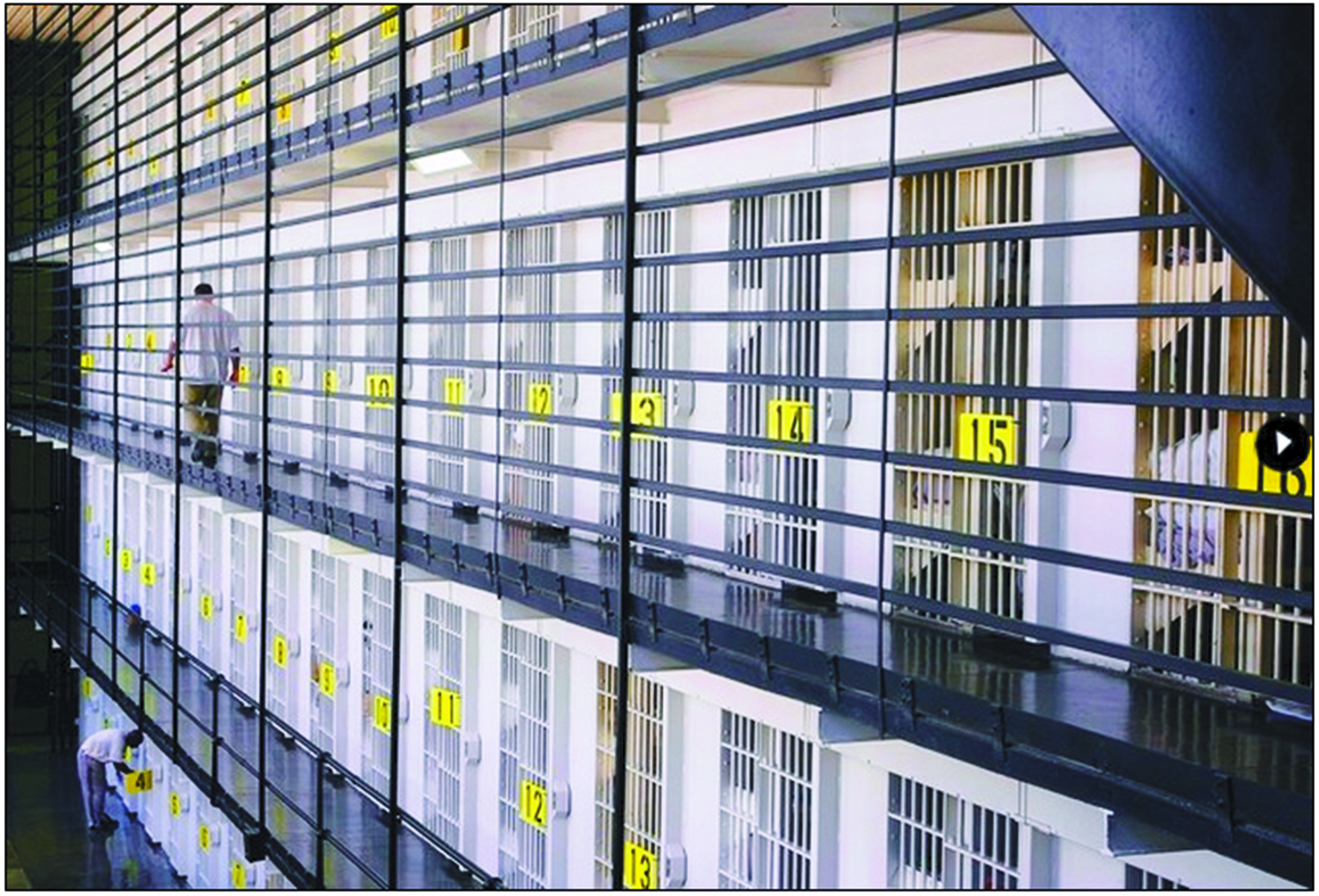

By some logic, then, the early release of these men is culpable for the loss of human life. Isn’t our criminal-justice system designed to improve public safety? Aren’t we to keep offenders off the streets, immobile, until a specific, court-ordered amount of time has passed and they’re deemed fit to rejoin society? That didn’t happen, and lo and behold: The criminals committed more crimes.

Heads must roll.

Hence the tense mood Monday during a Senate Law & Justice Committee hearing convened to investigate the matter, during which a Republican-led panel grilled DOC Secretary Dan Pacholke about who knew what when.

“Were you aware of this error in December 2012?” demanded Sen. Steve O’Ban (R-University Place).

“No,” Pacholke replied.

“It was a mistake you were made aware of by a victim’s family [in 2012]. Why didn’t [a fix] happen then?” asked Sen. Mike Padden (R-Spokane Valley).

“That’s a great question, Senator,” said Pacholke.

The gravity with which everyone is approaching the early-release scandal is surely intended to signal to voters that officials are being responsive to a DOC blunder tied to two deaths. Along with the Republicans’ prosecutorial line of questioning during the hearing, Pacholke called the error a “tragic event,” while Jamie Pedersen (D-Seattle) called it “a breach of the public trust.”

But everyone involved seems to be entirely ignoring the true scandal here: When convicts get out, they frequently reoffend.

In both homicides tied to the early release, the crimes were committed a mere month or two before the prisoners’ “real” release date. Would another month or two behind bars have made the difference? Why are we blaming the Department of Corrections for shoddy math, as opposed to shoddy “Corrections”?

The real problem here isn’t a technical error, it’s a fundamental one. If the majority of prisoners commit more crimes, some within weeks, it doesn’t seem as though our justice system is doing very much to address the root of the problem. And this isn’t just in Washington: Across the country, recidivism rates are through the roof. A recent study from the federal Bureau of Justice found that more than three-quarters of inmates released from state prisons in 2005 were arrested again within five years.

The risk of the current narrative surrounding the early-release scandal is that politicians, with elections approaching this fall, may revert to the lock-’em-up posture that has until very recently dictated America’s criminal-justice policy. Hearings like the one held Monday seem tailor-made to demonstrate how many votes can be lost in a world with too few people behind bars.

If that happens, it could come at the expense of the good work being done in this state to actually rehabilitate convicts, rather than simply keep them incarcerated.

As Sara Bernard reports in this week’s cover story, there are ideas out there that could help heal the wounds and overcome the circumstances that often contribute to an inmate’s crimes. Among them is a program called Yoga Behind Bars, which seeks to make inmates’ time in prison less traumatic. Too often, Yoga Behind Bars executive director Rosa Vissers tells Bernard, we as a society “punish, punish, punish and expect a different outcome.” If that’s the case, it shouldn’t scandalize us that offenders often reoffend, regardless of when they’re released.

Yes, technical errors that take the Department of Corrections 14 years to address should give us pause, and it doesn’t seem fair to allow faulty data management to decide an inmate’s fate. But using recidivism as political capital—suggesting that more time in jail is, without question, the key to deterring crime—seems just as unfair and, worse, unfounded.

editorial@seattleweekly.com