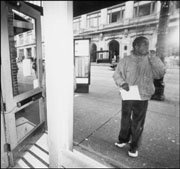

HOW LONG WOULD it take to get an offer of illegal drugs in the shadow of police headquarters? Three minutes? Two?

One. “What you waitin’ for?” says the rail-thin hustler in a ball cap as I arrive outside the Morrison Hotel at 6pm.

“Why?”

“Look like you want somp’n.” He smiles with gapped teeth.

“Like?”

“Smoke. Coke. Want cocaine?”

“The police station’s over there. Sheriff across the street. Security guard inside.”

“Don’t mean nothin’. What you want?”

No surprise, of course. Anyone who merely strolls past the 91-year-old red-brick Morrison, hostelry to the homeless, knows drug-seekers go to the neighborhood with the same expectation others go to Starbucks—to get their fix. It’s an old joke In the war on crime. A few paces from SPD headquarters in the Public Safety Building at Third and James, across the street from the sheriff’s headquarters in the King County Courthouse, along sidewalks brimming with prosecutors, judges, and city officials, the city-owned Morrison is Seattle’s handiest crime scene.

A recent safety assessment by the city notes that “the hotel is located in a high-crime area where drug dealing around the building is a daily reality.” But not all the problems are outdoors. From October 1998 to October 1999, for example, police were called 362 times to the Morrison for, among other things, 92 disturbances, 35 assaults, 16 thefts, six suicides, five robberies, and four dead bodies—natural or drug overdose deaths (the hotel also averages at least one 911 fire call weekly). In the first six months of this year, police responded to 158 calls—including 21 assaults, three rapes, and two deaths: a natural and a drug OD.

In the latter instance—a drug OD in May—police were called to the small room of James Mize, 54. He was found on his bed, shirt off, TV on. A rubber tourniquet, a blackened spoon, a needle cap, and needle tracks in his arm seemed to say it all. Almost. The cop who investigated the scene did not report finding a needle, indicating someone else had been in the room. But in a report, the officer noted investigators “did not find any suspicious circumstances surrounding Mize’s death.”

That’s correct in one sense. A drug overdose is something of a natural death at the Morrison, the rundown house that neglect built. The Seattle Housing Authority, a municipal corporation whose board is appointed by the mayor, operates the 205 units of subsidized housing and a first-floor shelter holding up to 250 a night. Residents include the addicted, the disabled, and the mentally ill, most living on disability and food stamps. Not all are saints—some are biding time between indictments—though the Morrison is mostly last-resort housing for the many down on their luck. But nobodies can be overlooked when convenient. The city has managed the Morrison for a quarter century and keeps losing its grip on progress. Up against the wall again, the SHA made a bold move in July: It formed a committee to study the problem.

Terrific, another blue ribbon panel, says Joe Martin, longtime Pike Market Clinic social worker. He tries not to be cynical as he recalls the many lives of the once-grand 1909 hotel. In the 1970s, “not even a hardened Skid Road denizen would think of renting a room there—too dangerous.” After a $4 million rehab in 1985 the place was “utter magic,” Martin remembers. Now? “Time and neglect have ironically brought this grand building back to where things were 20 years ago. Once again, it’s a matter of will, and money.”

He is backed by a mournful Morrison choir. “It’s a war zone,” says Rodney, a hotel resident who worries about having his full name published. He lives along a dim hallway of doorknobs. One day he left his room unlocked and returned to find a crowd of crackheads smoking away. “There’s fighting,” he says. “People come knocking on my door offering drugs.” He sees crack pipes on the windowsills.

Rodney’s response was typical as a survey taker from the Seattle Displacement Coalition moved through the building the other day asking residents how they were doing. “People throw syringes out the window,” said Richard, who moved in a week before. “It’s spooky, a lot of people have died in the building,” said Levi. Terri, there 13 months, said she doesn’t leave her room at night. Eddie, a one-year resident, wants to put a dead bolt on his door but can’t afford it.

The SHA’s own records show 31 of 79 residents recently surveyed felt unsafe. Some are more worried about the hotel’s condition—it needs $2.5 million in capital improvements, including a new boiler. In the lobby last week, an older woman told me she appreciates the roof over her head and isn’t frightened. But “my room has bugs, and the elevators always break down. That’s no good for the ones in wheelchairs.”

HE’S HEARD IT before, says John Fox of the Displacement Coalition, a local homeless-advocacy group. “What’s at stake is the future of this building and the health and safety of some of Seattle’s most vulnerable and disabled residents.” Repeated fix-its never seem to take, he says, while other efforts go astray. A $250,000 federal Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Safe Neighborhood grant in 1998 was to provide more security for the Morrison. But, Fox says, it was used mostly to hire a police community services officer and lease a car to patrol Pioneer Square while “ignoring the astronomically high incidence of crime in the building.”

According to SHA figures, $151,000 of the grant was in fact for one officer, whose position costs $5,853 per month. SHA spokesman Jim Kjeldsen says the grant reimburses police for an officer assigned “in and around” the Morrison neighborhood and wasn’t approved for “traditional ‘drug elimination’ activities.”

Though hotel policy is to not house anyone with recent criminal convictions for drug, property, or violent crimes, some get in anyway (residents have been known to allow unpermitted guests to enter and exit via fire escapes as well). The SHA, which has been trying to turn over the facility to a private management group since 1979, thinks crime is not as bad as it seems at the Morrison, although the SHA counts an incident only when a police report is written rather than when 911 is called.

Fox’s group has petitioned the Seattle City Council to appropriate $200,000 for improved Morrison security. He wonders why the SHA is “working on long-term plans while letting current conditions in the building continue to go to pot.” The SHA’s Kjeldsen says the city “is committed to housing this very difficult population, and our goal is to continue these services.” Staff has been added and the budget has been increased. Private security officers hired by local businesses also plan to set up an office at Third and Yesler. Seattle’s Office of Housing is stepping in, too. “We have experience with providing housing for populations with a lot of need for support services,” says spokesman Bart Becker. “That certainly describes the residents of the Morrison.”

The new reform committee will not have its first full meeting until the end of this month. A recommendation is even more months away. In the meantime, someone may want to walk over from police headquarters and speak to the pushers and players. It is not that far and there’s a place nearby to get doughnuts.