It shouldn’t take a rocket scientist to comprehend the state’s public- disclosure law. But Armen Yousoufian, 57, who once helped build missiles for Boeing, had to go where no man had gone before. He ran an eight-year gauntlet of closed King County government doors, bureaucratic roadblocks, and finger-wagging officials. They told him he just didn’t understand a state law that is intended to splash sunshine on the schemes of public servants.

Later this month, he is likely to show just how wrong they were. Yousoufian could be awarded up to $825,200 in public funds, although out of the goodness of his heart he is asking for merely $742,680. State law allows up to $100 per day in fines against public agencies that fail to disclose requested records. In Yousoufian’s case, King County—under executives Gary Locke and then Ron Sims—dallied for no less than 8,252 days, based on multiple types of documents Yousoufian sought over five years. The stalling dates back to the time of Yousoufian’s first request in 1997 for documents related to the proposed new Seahawks stadium, now called Qwest Field, which was built largely with public money for team owner and Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen. Frustrated by the runaround, Yousoufian sued, and a King County Superior Court judge in 2001 found the county’s actions “egregious,” handing out a $5-a-day penalty.

Sore winner, Yousoufian appealed and won a rehearing on the penalty amount. Today, he says, “We’re asking for $90 per day versus the original award of $5, which both appellate courts said was too low—and for the additional legal fees.” Those would be his attorney bills, $330,000, he says. Altogether, at a penalty hearing set for Aug. 19 in King County Superior Court in Seattle, Yousoufian could be awarded up to $1,155,000 in public money because a public agency thought it didn’t have to tell the public how it was spending public money.

That should be a stinging reminder to government officials and a victory for the little guy—although Yousoufian, a former Seattle hotelier, had some bucks to spend. Yousoufian’s landmark victories have also strengthened the state Public Disclosure Act (PDA). In two subsequent court rulings, his case was cited in the awarding of daily penalties of $50 and $75. Legislative amendments have also pumped up the disclosure law this year. State Attorney General Rob McKenna, who has made a strong PDA a priority, has launched a statewide tour to inform the public about new aspects of the disclosure law. Among them is a requirement that officials must help citizens narrow the scope of requests and not flatly reject them as too broad, an easy out.

The recent efforts to make governments more respectful of the public-disclosure law, whether through litigation or outreach, are a good thing, but the law itself could use more work. The PDA still contains a loophole big enough to swallow up roomfuls of filing cabinets. A government official who wants to lock a record from public view can copy it to a government attorney and argue that it is attorney- client privilege that precludes disclosure. That aspect of the law was challenged last year by Seattleite Rick Hangartner, who sought documents from City Hall about light-rail permits. In Hangartner v. City of Seattle, the state Supreme Court (attorneys all, mind you) ruled against him and allowed the city to withhold records on an attorney-client basis, even though their release posed no threat of litigation.

“The nonlitigation-based attorney-client privilege the Supreme Court created in Hangartner will continue to be the great hiding place for information the government does not want to disclose,” says Michele Earl-Hubbard, whose law firm, Davis Wright Tremaine, represents Seattle Weekly and The Seattle Times, among other media outlets. “This will continue until the Legislature, the Supreme Court, or the voters of Washington take the law back to the way it was before.” Earl-Hubbard, who serves on the board of the nonprofit Coalition for Open Government (www.washingtoncog.org), says all that’s needed is the insertion of four words. To be exempt, records should have to be “relevant to a controversy”— relevant to completed, existing, or reasonably anticipated litigation. But proponents of such a change have run into the “government-lawyer lobby,” as Earl-Hubbard calls it—lobbyists supported by taxpayers to oppose opening records to taxpayers.

Obviously, there’s need for more public and media access to records. Apparent or actual fraudulent and incompetent government practices abound. But it wasn’t just high-profile bureaucratic shortcomings that voters sought to shine a light on when they passed the measure in 1972. The introduction to Chapter 42.17 of the Revised Code of Washington says it should be a matter of routine: “The provisions of this chapter shall be liberally construed to promote complete disclosure of all information respecting the financing of political campaigns and lobbying, and the financial affairs of elected officials and candidates, and full access to public records so as to assure continuing public confidence of fairness of elections and governmental processes, and so as to assure that the public interest will be fully protected.” Reads the preamble to the public-records statute and a companion law, the state Open Public Meetings Act (Chapter 42.30), passed by the Legislature in 1971: “The people of this state do not yield their sovereignty to the agencies which serve them. The people, in delegating authority, do not give their public servants the right to decide what is good for the people to know and what is not good for them to know.”

That said, both the open-records and open-meetings laws have numerous exemptions, many of which have been added by the Legislature over the years, effectively chipping away at their original intent. For among other reasons, elected bodies can hold closed, “executive” sessions to consider such matters as those affecting national security, real-estate transactions and contract bids, and certain personnel matters. The meetings law also allows closed sessions to discuss “potential litigation,” but not in the blanket sense—there has to be an actual threat of litigation or a lawsuit. There’s no way to know if city councils and boards and the like are adhering to the law—we have to trust them. Actual votes, at least, must be public.

The open-records law has exemptions, too. Exempt are some material in personnel and law-enforcement investigative files, certain records containing personal or private financial information, and proprietary business data and trade secrets. There are dozens more exemptions to disclosure that are arcane and debatable, but nothing with an effect as sweeping as last year’s Hangartner decision, which makes it possible for a public official to send a carbon copy of an e-mail, memo, or document to a government attorney, for no particular reason but to keep it confidential.

If the public can’t demand access to such documents, citizens and journalists increasingly must rely on agency employees to blow the whistle on mis-behavior or unjustifiable secrecy. Populist Olympia attorney Shawn Newman and the Evergreen Freedom Foundation’s Jason Mercier think one answer is a state false-claims law, similar to an existing federal whistle-blower’s law. It could allow citizens to obtain denied documents through court proceedings while also pursuing civil charges against an agency. The public or government workers would have the ability to come forward in a protected status and collect damages— the latter a “major incentive for such citizen involvement,” they say.

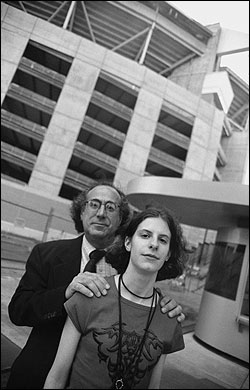

Yousoufian, though, wasn’t thinking of such payoffs when he wrote a public- records request on May 30, 1997. His inquiry was inspired in part by his daughter, Marysia, who wondered about Safeco Field. Why was it built next to a perfectly good stadium, the Kingdome, that already had a roof on it? He didn’t understand it himself, so he went looking for explanations for that and plans for the new football stadium to replace the Kingdome. As a businessman interested in taxes that might affect the University District hotel he has since sold, his initial records request was for “studies indicating that the ‘fast food’ tax had not been passed on to consumers (referred to by Ron Sims in an interview on KUOW)” and other studies on the stadium proposal. As the bureaucracy went into full stall, the native New Yorker became increasingly curious about the deeper backstory of the state’s and King County’s deal with Allen. Yousoufian used his self-described “nerd” credentials to obtain and pore over government contracts, e-mails, and letters. The closer he got to the truth, the harder the government pushed back, taking weeks, then months, then years to respond to his records requests.

Instead of giving up, Yousoufian was energized by the rejections. “They picked on the wrong Armenian!” he liked to say. He evolved from businessman to crusading documents diver. Among other developments, the records he unearthed helped Seattle Weekly report how billionaire Allen engineered a deal for a $430 million stadium that wound up costing taxpayers close to $1 billion when interest is figured in. Allen, relying on a loan from the National Football League, paid a comparatively small amount out of his pocket (see “After Further Review,” Feb. 12, 2003).

Ironically, the Public Disclosure Act itself became an obstacle. When Yousoufian rightly tried to wield its penalties to pry loose more records, the court tamped down fines intended to inflict pain on deceptive public agencies. His initial victory in 2001 earned him just $25,450 based on a fine of $5 per day for each of the 5,090 days the county stalled. He also got about $89,000 in attorney fees. To Yousoufian, that didn’t pay for his time nor send the right message. He appealed. A state appeals court and then the Supreme Court both agreed a higher penalty was necessary for the county’s gross negligence and added 3,162 penalty days to the clock. The original trial court now must decide, Yousoufian says in court papers, “the third factor in the equation based on the circumstances of King County’s failure to comply with the law, its culpability, and what it will take to deter a large, wealthy jurisdiction like King County from future violations.”

In a trial brief, Yousoufian’s attorneys note that the county has now agreed the original fine should, in all fairness, be doubled—to $10 a day. Well, if the court “is to use the full penalty scale, and if culpability, along with deterrence, is to be the measure of where a violation fits on the penalty scale, what would a case look like that fell somewhere in the $85–$90 range?” the attorneys ask. “It would be a case that looked like Yousoufian’s, a case of repeated and prolonged gross negligence. . . . ” They point out that the Supreme Court said King County told Yousoufian all documents had been produced when they had not, told him archives were being searched when they were not, told him documents were being compiled when they were not, told him hundreds of hours were spent retrieving requested documents when they were not, and told him only the county executive’s office was responsible for retrieving executive documents—again, not.

Observed the high court: “When the county did make an informed effort to find the documents, they were located and produced within a couple of days. . . . ” As Yousoufian describes it: “I was stonewalled.” In two weeks, he finds out how much the county spent to build that wall. He thinks he’ll be satisfied. But he can always appeal.