Sharon Maeda is on TV. The date is August 3, 2015. The Seattle activist and former White House staffer is standing in the press conference room on the seventh floor of City Hall, surrounded by the mutual-appreciation society that is Seattle’s political elite: Mayor Ed Murray, more than half of the City Council, the city attorney, and the chief of police, plus a row of leaders of immigrant communities so long it crosses the room.

Before her, the floor is jammed with reporters and observers, pens and pads and recorders and cameras poised, waiting to hear what the stout, earnest mayor beside her has to say. Hours before, Maeda had heard that Murray was going to release a statement on the recent murder of local hero Donnie Chin. She dropped everything and hightailed to City Hall, where she took a seat and waited to hear the big news. Then one of the mayor’s staffers asked Maeda to join the human backdrop for Murray’s announcement.

She’s expecting some kind of announcement about Chin, whose killers have not been arrested: something like “We found the shooter” or “We know which gangs were involved” or even “We’re close to announcing new information on Donnie’s death.” The cameras are already rolling by the time she glances down at the prepared notes on the podium in front of Murray. CLOSE HOOKAH LOUNGES, it reads in big letters at the top. Maeda looks again just to be sure she’s not hallucinating, but the letters are still there, taunting her from the page.

“Oh, ‘blank,’ ” she thinks. “I gotta get out of here.”

But standing in front of a live video feed, there’s no way to tactfully retreat—no way to leave without storming out. So Maeda stares hard at the floor, her hands clasped in front of her waist as though at a funeral or a disciplinary hearing. Murray begins to speak into the podium microphone.

“Good morning,” he says, “and thank you for being here today. In the last few years, Seattle has seen an alarming rise in violence and illegal activities associated with hookah lounges.”

Maeda understands the connection. The shooting took place in the early morning about a block away from King’s Hookah Lounge on Lane Street, where late-night revelers were known to congregate.

But she doesn’t like it.

As she’ll later say, Murray’s plan to shut down hookah lounges isn’t much different from the political rhetoric that arises later in the year. “ “[This] is like Donald Trump saying, ‘We’re not going to let any Muslims in,’ ” she later says. But she’s trapped. She grits her teeth, keeps her eye on the carpeted floor.

Maeda’s misgivings were well founded. Following Murray’s great roar against violence at hookah lounges came equally loud roars of racism. Over the next month, the Murray administration squirmed in the face of public controversy, trying desperately to please competing constituencies.

Almost half a year after Chin’s death and the hookah non-crackdown, few are satisfied with the results. No arrests have been made in Chin’s case, and the hookah lounge that first incensed the International District remains open. The aborted attack on hookah lounges left many East Africans feeling scapegoated by a city administration that needs to look tough, while the residents of the ID who’d called for sanctions in the first place have nothing to show for their efforts.

All the while, memorials for Donnie Chin remain piled outside his small shop in Canton Alley—sad and drenched reminders of the most shocking crime of 2015, and the bizarre City Hall spectacle that followed it.

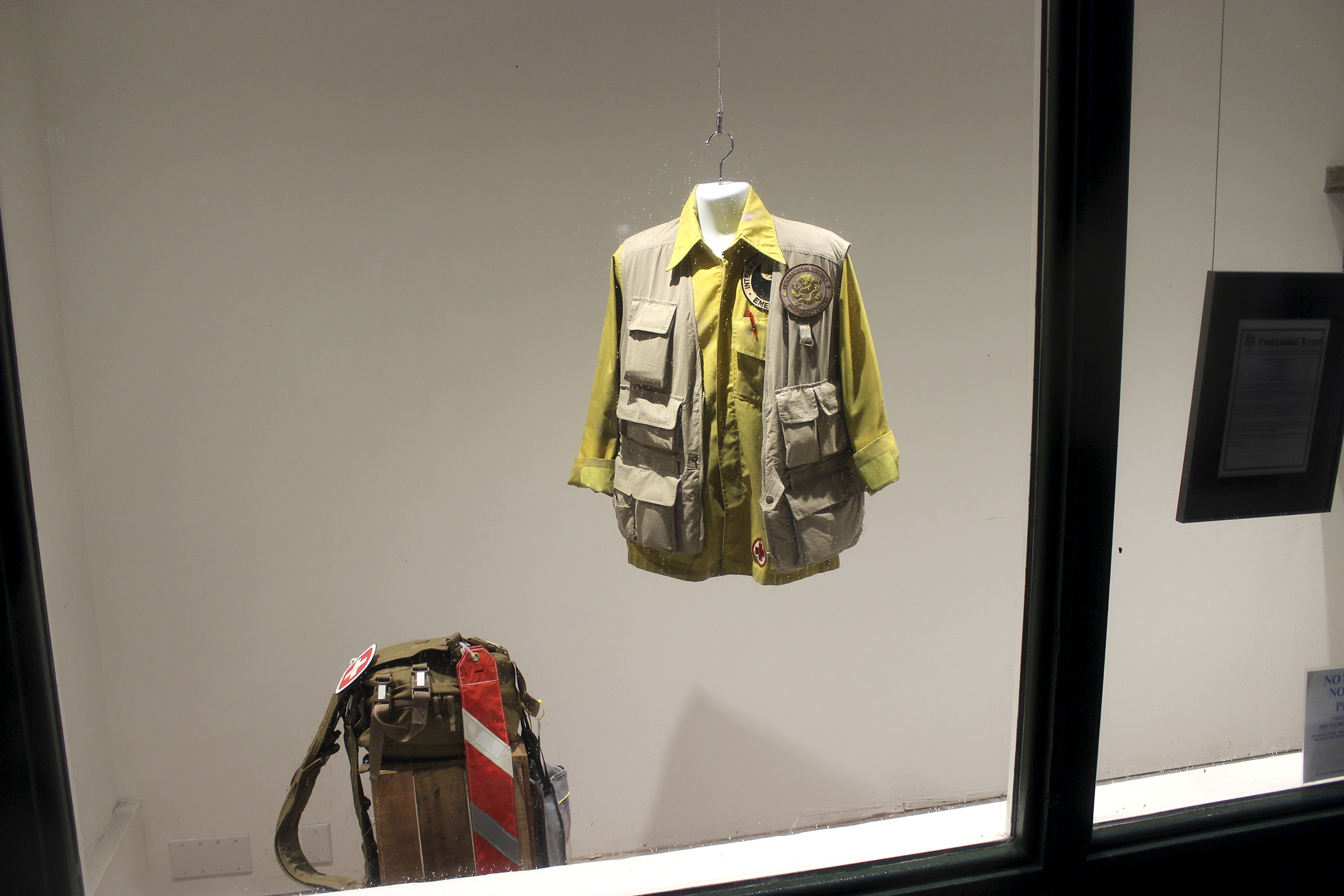

In the wee hours of the morning of July 23, Donnie Chin was gunned down in his car, caught in the crossfire while responding to gunshots in the International District. He died as he lived: serving the ID as a one-man emergency response unit, on call 24/7. The weight of his death hit everyone who knew him like a gunshot to the chest. A cloud of grief descended on Chinatown, which even today hasn’t fully dissipated.

With grief came the demand for justice. While the killers seemed to disappear into the night like fading smoke, many believed the conditions for Chin’s death were laid by King’s, where anyone 18 or older could while away the night time hours inhaling fancy tobacco fumes through an octopus of twisted inhalation tubes. Open later than bars, residents near King’s were accustomed to hearing late-night carousing, fights, and occasional gunshots. To some, the problem and the solution seemed equally simple: Hookah lounges cause violence, so shut down hookah lounges.

That logic was what led Bob Santos, the legendary activist, to lead dozens in protest against King’s during the nights that followed Chin’s death. “What do we want?” he chanted to protesters. “Close it down!” they replied in unison.

Some East African leaders joined the call, penning a letter of support saying they endorsed closing the lounges because they attracted violence and because smoking is unhealthy. “Despite the long history of violence surrounding hookah lounges,” they wrote, “we have not seen any of these business owners take serious steps to address our community concerns.”

Long history, indeed. Deputy Mayor Hyok Kim says that while angst over Chin’s death was the most obvious spark for August’s firestorm of anti-hookah sentiment, the smoky lounges had been on Murray’s mind since last year. That’s when he found himself comforting the mother of another shooting victim, Mohamed Osman, who was killed in early June 2014 near Casablanca Hookah Lounge, also in the ID. According to Kim, Osman’s mother personally asked the mayor to do something about violence near hookah lounges—a request that “has been weighing heavily on the mayor ever since his first year in office,” she says.

Chin himself repeatedly raised alarms in the ID over what he considered blatant criminal activity emanating from hookah lounges.

However, Murray felt his hands were tied, mayoral staffer David Mendoza says. “The ability for the city to actually close businesses is incredibly limited,” he says.

Following Chin’s death, though, inaction was no longer an option. At a community meeting the day of his death, Kim says, “There were some very strong voices who expressed their deep concerns about what was going on in Chinatown/ID with a couple of problem hookah bar lounges.”

But neither the ID nor the ethnic groups within it are a monolith. No sooner had Murray uttered the words “alarming rise in violence and illegal activities associated with hookah lounges” than local resistance, and suggestions of racism, took root in the body politic. An August 10 City Council meeting was filled with commenters decrying the crackdown.

“The closure of hookah lounges,” said lounge owner Nabil Mohamed, “is orchestrated to make the mayor appear decisive about ending violence without addressing the actual issues” undermining public safety in the in the ID.

One week later, both pro- and anti-hookah factions again lobbied the Council to support and oppose Murray’s plan.

Despite what the mayor’s office says was a resolve against hookah lounges that had reached back to the beginning of his administration, Murray struggled to maintain it in the face of protest. After reciting statistics on hookah-proximate fights and shootings, Murray was asked for comparable statistics on violence near bars. Murray had no answer. Neither did anyone else. (A more recent geographic analysis of the location of police 911 responses shows that the lounges are not particularly associated with violence and crime.)

Missing that key statistic, the Murray administration pivoted concern toward the health impacts of indoor smoking (which is banned in Washington state, though hookah-lounge owners say that they run private clubs, which are exempt).

This argument had the advantage of holding weight in the East African community, and in science. Ubah Warsame worries about peer pressure on young people to smoke hookah. “I am a mother of three children,” says the local health educator and interpreter, “and I think of all the youth who think this is the thing to do.

“They can be there three to five hours, just sitting there,” she says. “It destroys their health, lungs . . . It’s not good for them” and costs precious time and money.

However, to the public, talk of the health impact of hookah-smoking was all the more baffling. Was the crackdown on hookah lounges still about Donnie Chin? Or lung cancer? As Josh Kelety of PubliCola put it in early August, seizing the irresistible metaphor: “Murray’s motivations are hazy.”

Whatever the effects of hookah lounges on health and violence, the Murray administration switched tone again on August 28, one day after meeting with hookah-bar owners for the first time. “Yesterday’s meeting was the first opportunity for everybody to sit at the same table and understand fully what the regulatory landscape looks like and recognize pathways to get into compliance,” mayoral staffer Brian Surratt told The Seattle Times. But weren’t hookah bars a pressing threat to public safety—a danger so clear and present that shutting them down was an integral part of “stopping violence in our streets,” as Murray put it on August 3? “My conversations with the [hookah] businesses right now are strictly confined to helping them get into compliance,” Surratt told the Times.

Examined through the lens of that August 3 press conference, the Murray administration’s shift was striking: What had been a top-level public-safety priority had, within a month, become a matter of bureaucratic box-checking.

Today, asked what steps the city was taking to address hookah lounges short of closing them, mayoral staff point to a couple of things. One is a pending Racial Equity Analysis from the Office of Civil Rights based largely on discussions with affected community members, trying to suss out the implicit effects of shuttering hookah lounges on East African Seattleites and other marginalized communities. Another is a pending King County Superior Court decision on a case between Seattle/King County Public Health and a Medina hookah-lounge over whether the latter is operating in violation of state smoking laws. A spokesperson for Public Health says they’ve contacted a dozen hookah lounges overall, but none has yet changed its operations to comply with state law.

Still, in an interview with Seattle Weekly, Murray says progress is being made. Last week, the mayor convened a new ID task force to “build on Donnie’s legacy” and advise on local economic and safety issues, according to a press release.

Murray also says he’s already started to hear good things from ID leaders about their hookah-lounge neighbors. “I am hearing from some of the leaders in Chinatown and Little Saigon that they’re having a very different relationship with [King’s],” he says. “Hopefully what we’re seeing is a willingness to find a model that would get them into compliance . . . [and] engaging with the neighborhood to become better neighbors.”

This all sounds good, but none of it’s very concrete: a pending analysis, a pending court case, a fledgling advisory group. All in all, the city’s current relationship with hookah lounges can be summarized in a word: “conversations.”

One big question—the central question in this saga since the beginning—remains. When Murray called that August 3 press conference, was he motivated by a true belief that the presence of hookah bars represented a serious public safety threat, or by a desire to look responsive to the killing of Donnie Chin? After all, Chin had been complaining to the city for months about violence outside King’s, so it’s plausible that Murray feared that public opinion would blame him for Chin’s death. Alternatively, did Chin’s death gave the Murray administration an excuse to go after hookah lounges? In short, did Murray play politics with the death of a beloved citizen?

In response to the suggestion that he hijacked the publicity around Chin’s death, Murray and his staff stress that the short-lived crusade against the lounges was brought to them by affected residents, not the other way around. One staffer provided a copy of a petition against hookah lounges received by the city. There are hundreds of handwritten signatures. A letter signed by 18 East African community leaders, dated August 12, urges the mayor to “support enforcement of the law and the closure of unlawful indoor smoking establishments.”

“Probably the mistake I made,” says Murray, “was acting. Because if I hadn’t acted, the [news] stories would be about Chinatown and Little Saigon up in arms, and the Chinese and Vietnamese communities up in arms because I wasn’t acting.

“So if I made a mistake, it’s probably I acted too soon. The political thing for me to do would have been for those communities to turn on me and then have acted.”

Maeda agrees that Murray acted too fast on the Chin issue, but cautions against blaming the community. For her, the Murray administration just needs to impress people, all the time. “If you haven’t noticed, he does that a lot,” says Maeda, referring to Murray’s tendency to be visibly on top of the issue du jour. “I was actually very impressed [with Murray] the first few months he was in office. I said, ‘Oh my God, he’s gonna be OK.’ ”

There seems, she says, to be “a need to come out first,” to “get ahead of everything . . . ‘We’re going to be first, we’re gonna be on top of this, we’re going to be on top of everything.’ Well, it’s impossible to be on top of everything. I think that his office is driven by that focus to want to be first,” she says. To some extent, that drive to be first can be a good thing, pushing the mayor to respond to public feedback. But taken to an extreme, it becomes a liability, she says.

“I don’t expect my mayor to be everywhere there’s a news story.”