The proposal to replace the dangerous, 53-year-old Alaskan Way Viaduct with a tunnel along Seattle’s central waterfront already has a disparaging nickname: the Big Dig. That nickname, of course, originated in Boston, where it described the replacement of an elevated portion of Interstate 93, which separated downtown Beantown from Boston Harbor, with a complicated series of tunnels. Boston’s Big Dig also earned infamy as the nation’s most expensive public-works project as its cost rose from an estimated $2.6 billion in 1983 to $14.6 billion today. While there are enough similarities between the two projects that the nickname for Seattle’s undertaking will undoubtedly stick, the differences are important for Seattle voters to grasp as the city prepares for November’s vote on how, or whether, to replace the viaduct: with another elevated structure, or with something on or below the ground.

From an engineering standpoint, it is absurd to compare Seattle’s proposed cut-and-cover tunnel to Boston’s Big Dig. The Boston project, writes Dan McNichol, its former deputy director of public affairs, in his book The Big Dig, “is the largest and most complex urban infrastructure project ever undertaken in the modern world. It is bigger in scale than the Panama Canal or Hoover Dam and more complex in its planning, engineering, and construction than the two combined.” Boston’s project consisted of three tunnels—a three-mile tunnel under saltwater Boston Harbor, a 1.5-mile tunnel under Boston’s commercial district, and a 1,100-foot, 11-lane tunnel connecting downtown and South Boston. Oh, they also built the world’s widest cable-stayed bridge. Seattle’s tunnel would be just over a mile long, would be under a street with no structures above—much less water—and would have six lanes. “It’s kind of a Small Dig,” says Clark Williams-Derry, a researcher with Northwest Environment Watch and an adamant tunnel opponent.

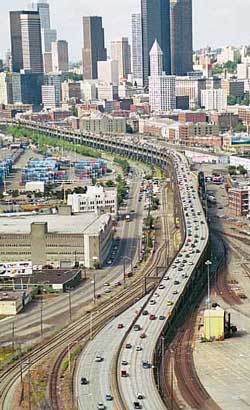

Boston’s Big Dig is eight miles long with 121 lane miles, 80 of which are in a tunnel. Seattle’s full project “corridor” would begin in the north on Aurora Avenue North at the intersection of Ward Street—four blocks north of Mercer Street on the eastern slope of Queen Anne Hill—and would run south to a point on Highway 99 three blocks south of Qwest Field. That corridor is four miles, with 20 lane miles, 6.9 of which will be in a tunnel (5.2 lane miles in the new tunnel, 1.7 lane miles in the existing Battery Street tunnel).

Lately, just to make things more confusing, Mayor Greg Nickels, the most prominent backer of an underground solution, and the Washington State Department of Transportation have proposed a “core tunnel” project that would essentially be the first stage of the work proposed for the entire corridor, leaving out the expensive sinking of Aurora Avenue north of the Battery Street tunnel. Comparisons in this article are to the entire project corridor, not just the core tunnel.

Boston’s Big Dig involved digging up 16 million cubic yards of soil; Seattle’s entire project, including the tunnel, would displace around 2 million cubic yards.

University of Washington civil engineering professor Steven Kramer specializes in geotechnical earthquake engineering and first exposed the dangers of soil liquefaction during an earthquake under the existing viaduct. Kramer says the soil in Boston presented much greater challenges than the soil along Seattle’s waterfront. “The level of risk is a lot lower than in Boston, where they are dealing with that Boston clay,” says Kramer, pronouncing the final two words as if they were the vilest insult imaginable. Kramer explains that Seattle’s tunnel area has between 20 feet and 60 feet of fill on top of compacted glacial till. WSDOT plans to scoop out the fill—all 2 million cubic yards of it—and build directly on the glacial till. “The glacial till material would be very competent,” Kramer says. “Twenty-five thousand feet of ice was sitting on it about 12,000 to 13,000 years ago. It is very dense and strong.” Kramer says this construction technique involves no actual boring, so he hesitates to even call it a tunnel, preferring to refer to it as an excavation. “We build excavations all the time,” he says. Kramer compares the process to building a Seattle skyscraper, where a huge trench 60 feet deep is dug for a building’s foundation, to be tied into the glacial till underlying the city. “You are using conventional construction techniques,” says Kramer.

Kramer did a study of the seawall that keeps Elliott Bay from flooding the filled-in central waterfront and found it decrepit and, like the viaduct, in danger of collapsing in an earthquake. He expresses confidence in WSDOT’s plan to use the tunnel’s western wall to replace the part of the seawall that runs from King Street in Pioneer Square to the proposed tunnel’s northern terminus near Pike Street and the Seattle Aquarium. “It gives you a real strong, beefy wall,” says Kramer.

WSDOT documents explain, “The wall would be constructed of 4-foot-diameter drilled (concrete) shafts that would extend up to 90 feet below the ground. The shafts would overlap to form a continuous wall. . . . ” This is a common structure called a secant pile wall. Essentially, the wall is built before excavation. Kramer says water leakage through a secant pile wall is not much of a concern. In contrast, Boston’s Big Dig has had major problems with leaks. In Boston, contractors used an experimental technique to save money and space in an I-93 tunnel under Boston’s commercial district. Most tunnels like this are built by constructing reinforced concrete walls called “slurry walls” as you dig a trench. Then a full concrete box is poured between the slurry walls to form the final walls of the tunnel. Seattle’s tunnel would be constructed in this conventional fashion. Boston’s I-93 tunnel skipped the final step of pouring a concrete box and relied on slurry walls alone. Boston’s slurry walls, which are 12 stories deep in some places, have not performed well.

Engineering is not the only aspect of a megaproject like Seattle’s tunnel, however. The enormous costs of megaprojects and the inexorable tendency for them to increase are something that every critic of Seattle’s tunnel mentions. WSDOT takes this problem seriously and is being very rigorous in its effort to address it. The department has a link on its Web site (www.wsdot.wa.gov/projects/projectmgmt/riskassessment) to a tough-minded study of this tendency for megaprojects to bust their budgets. In 2002, Bent Flyvbjerg of Aalborg University in Denmark concluded an examination of 258 large public-works projects between 1910 and 1998. His results are startling: The costs of nine out of 10 projects were underestimated. Bridges and tunnels were underestimated by an average of 34 percent. No improvement has been made in cost estimating over the past century, while scientific knowledge has increased greatly in the same period. So Flyvbjerg attributes this continuing failure to accurately predict costs to the fact that estimates were lies rather than erroneous.

State Transportation Secretary Doug MacDonald’s experience as the executive director of the Massachusetts Water Resource Authority from 1992 to 2001 gave him two invaluable experiences with megaprojects. First, he completed a 10-year, $3.8 billion megaproject called the Boston Harbor Cleanup Program—on time and on budget. Second, he had a ringside seat as Bostonians went ballistic over the Big Dig’s cost overruns. “The project was mismanaged,” says MacDonald. “The Big Dig suffered a terrible political environment. It was turned into a fund-raising machine for the governor.” MacDonald says he is determined not to see those mistakes repeated in Washington. “The project culture we have tried to instill is the ‘not-Big-Dig’ culture,” he says.

MacDonald and his department have developed a new budgeting tool called the Cost Estimate Validation Process. They are so excited about it, they copyrighted the name. WSDOT brings together a group of experts for a week and asks them to assess the risk elements of a project. In the case of the waterfront tunnel, the experts examined 80 elements of the project. Each element is assigned a dollar value and a probability of occurring. WSDOT then builds a mathematical model that gives a range of cost estimates for the completion of the project—$3.7 billion to $4.5 billion for the entire project corridor and $3 billion to $3.6 billion for the core tunnel project that excludes work north of the Battery Street tunnel. The range means that there is a 90 percent probability that the core tunnel project will cost $3.6 billion or less. WSDOT is very careful to note that the cost is an estimate based on a design that is only between 2 percent and 10 percent complete.

UW professor Kramer says, “It’s a tremendous development. It’s a rational, objective way to try to quantify the risks. It’s not foolproof, but it’s better.”

Boston’s Big Dig used a cost estimation process that did not, among other things, account for inflation. Since construction in Boston began in 1991 and continues to this day, inflation costs are a significant part of the whole. In addition, the scope of the project kept expanding, and the design kept changing as the Big Dig was under construction. Costs were hidden to placate the federal government that was picking up most of the tab.

Still, WSDOT’s new cost estimating process has not been used on a project that has been completed. Only time will tell if the Cost Estimate Validation Process really represents progress in cost estimating for public projects or is just a trendy tool. Seattle City Council member and tunnel skeptic Peter Steinbrueck is dubious. “Nationally, megaprojects are 40 percent over budget,” Steinbrueck says.

Steinbrueck is concerned that the Seattle tunnel and Boston’s Big Dig suffer from the same fatal flaw: The more and better highway capacity a city provides, the more vehicles show up to use it. Steinbrueck observes ruefully that the Seattle tunnel “will probably be congested on the day that it opens.” While everyone agrees that the current viaduct is unsafe and must be taken down as soon as possible, not everyone thinks we should spend money replacing it.

Boston’s Big Dig certainly provides some sobering news in this regard. Travel times have decreased significantly throughout the Big Dig and by as much as 85 percent on some of the roadways, according to the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority. At the same time, the number of vehicles that are using the Big Dig has jumped much more quickly than anticipated, according to Frank Salvucci, the man who began the project as Massachusetts secretary of transportation. Salvucci, now a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told Bloomberg News in 2005 that parts of the Big Dig already carried as much traffic as was projected for 2010.

The Seattle tunnel would replace all the highway lanes that currently exist, but it would not increase vehicle capacity. WSDOT hopes that shoulders and wider lanes will improve traffic flow.

Steinbrueck argues that since the region is experiencing such explosive growth, we must radically depart from transportation policies that favor cars over mass transit. If Seattle decides to spend seven to 10 years and billions of dollars to rebuild another highway, Steinbrueck believes we will have missed a key opportunity to end our “love affair with the automobile.”

Seattle City Council President Nick Licata thinks it’s vital to replace the viaduct’s capacity, although he prefers a viaduct rebuild to a tunnel. “There is no option anywhere for mass transit,” he says. While he acknowledges that the region will reach a point of congestion where mass transit is the only solution, he believes that replacing the viaduct’s capacity can give us the time we need to develop such a plan. “It took eight years to finally reject the monorail,” he says. “It will take time.”