Although South Park parent Rebecca Galarosa received several messages from Seattle Public Schools in recent weeks about potential school bus closures, “I really didn’t think it would go this far,” she said outside of Concord International Elementary School after picking up her two youngest children on Wednesday afternoon last week. Her 8th grade daughter normally takes the bus home in the afternoons, but on Wednesday, Galarosa picked her up at the nearby public library due to the one-day bus strike.

Once the drivers announced the protest on Tuesday, Galarosa called other parents in the neighborhood to discuss alternative arrangements. She planned on driving as many students who didn’t have a ride home as she could fit into her gray mini van. Single parents who lacked the money for a metro bus or worked full-time and couldn’t adjust their schedules were the ones most impacted by the strike, Galarosa said she observed.

On Wednesday morning, her husband had to clock in late to work as a customer service agent for a local roofing company to drop off their 8th grader and three additional students who lacked transportation for the day at Denny International Middle School. “We felt very upset,” Galarosa said.

Galarosa was one of the many parents who had to adjust their schedules due to the Seattle school bus strike on Wednesday that affected about 12,000 students. The Teamsters Local 174, the union representing more than 400 yellow school bus drivers, stood at bus lots turned into picket lines to demand more adequate healthcare and a retirement pension. The union has been in negotiations with Ohio-based school bus contractor First Student since July. Bus service resumed on Thursday, although the union and contractor still hadn’t come to a resolution by Wednesday evening, said Teamsters Director of Communication and Research Jamie Fleming. A longer strike could be called in the future if a negotiation is not made, which worries parents like Galarosa who have to juggle multiple drop offs and potential time off from work.

Galarosa has already discussed carpool plans with her husband and neighbors if another strike is announced in the future. “It’s going to probably affect me taking a little bit of time off to be part of that,” Galarosa said about the carpools.

Galarosa works for a health care provider from her home in Cesar Chavez Village and said that many parents decided not to send their children to school on Wednesday. The children were playing outside unattended, she said, which disrupted her workday. “They’re loud outside and I have to have my calls private, so I don’t at all look forward to the kids staying at their places,” she added.

Seattle Public Schools spokesperson Kim Schmanke said in an email to Seattle Weekly that the district informed the parents of a possible strike for several weeks. In lieu of school bus rides, families were relying on carpools, public transportation, walking, or car-for-hire services like Uber, she said. In a follow-up email on Friday, Schmanke said that the district found a three percentage point increase in excused and unexcused absences on the day of the strike compared to November 15, the most recent Wednesday when all schools were in session.

Although the district encourages First Student and the Teamsters to come to an agreement soon, the union continues to blame the contractors for leaving many drivers without healthcare and not providing sufficient retirement plans.

“We just want to emphasize that we’re out here fighting for something that’s so important and that most people take for granted that these people don’t have,” Fleming said about the few bus drivers left standing behind her at South Park’s First Student bus lot late Wednesday afternoon.

The drivers picketing at First Student bus lots in South Park and Lake City for 12 hours shared stories of filing bankruptcy because of medical costs, Fleming said. One 26-year-old worker had untreated cancer because she lacked medical insurance.

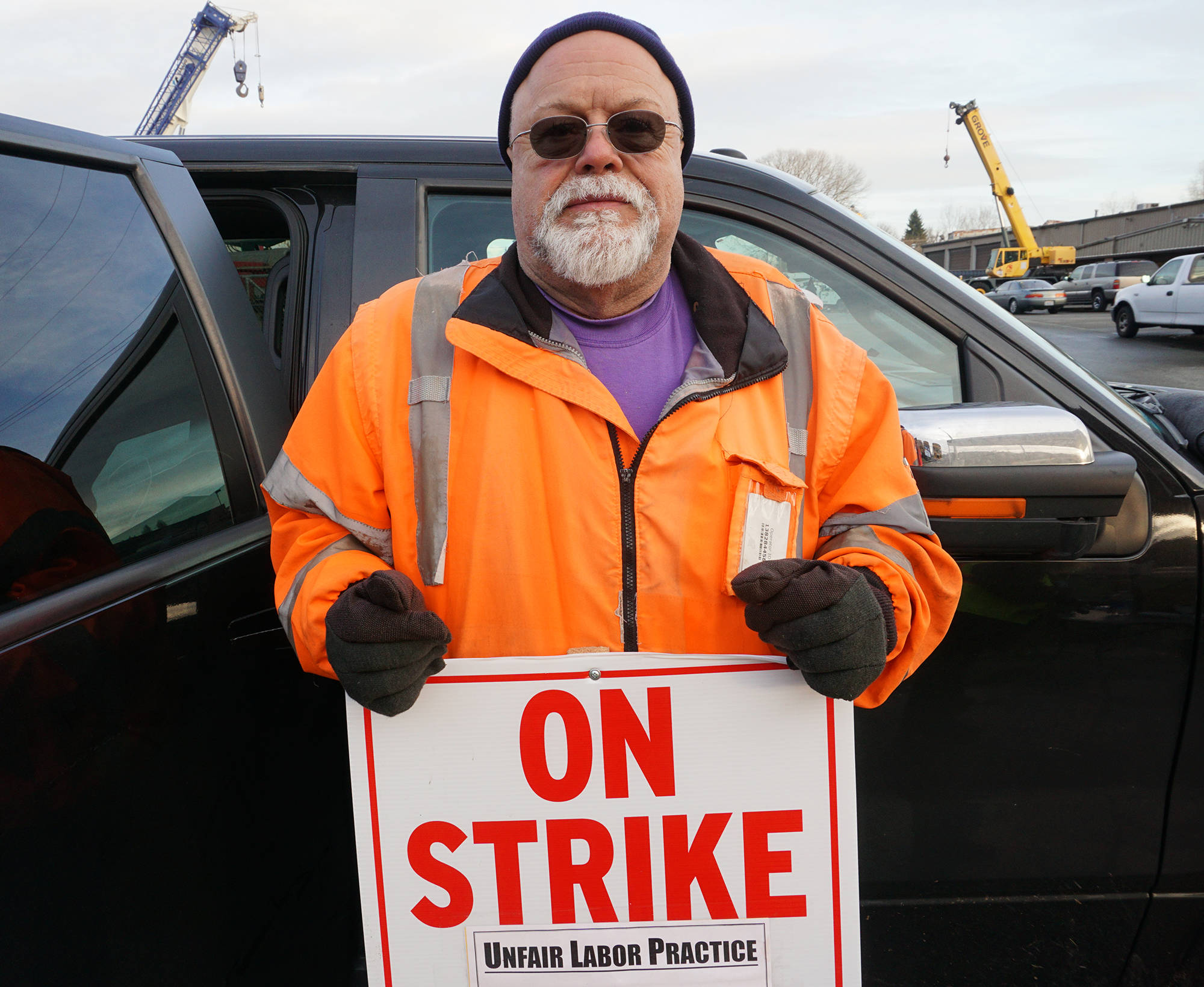

Dana Bland, 63, is one Teamster who had to declare bankruptcy in 2015 when he couldn’t shoulder the costs of his medical treatment for chronic pancreatitis. Although he’s been driving school buses for nearly four decades, he says that the medical insurance he receives through First Student is the worst he’s ever had. In November 2013, he spent three days in the hospital that cost him more than $40,000, but the insurance only covered about a quarter of it, he said.

“The drivers care about the kids, or we wouldn’t be doing it,” Bland said while shivering from the cold. He enjoys the job, but says that he would like health insurance that covers more than “an office visit and a physical.”

“The effects on people’s lives have been real and dire,” Fleming said as several green recycling trucks passed by and honked in solidarity. The remaining drivers circumambulating the sidewalk shook their signs bearing the words “on strike” in red letters. Fleming was one of about 12 Teamsters hit by one driver who crossed the picket line that morning. One was taken to urgent care, but no one was seriously injured, Fleming said.

In a prepared statement, First Student Senior Director of Corporate Communications Chris Kemper blamed the union for not meeting them halfway. He said that the contractor recently offered the union additional funding for healthcare and retirement, but the union rejected it. Kemper added that it’s standard for companies to not offer healthcare to an employee who works part-time for 36 weeks a year.

“We strongly encourage the union to join us in finding a resolution. Our goal is to reach an agreement that’s fair and equitable for all parties. We want to partner with Local 174 leadership to ensure the best possible outcome for our drivers, our students and the community,” Kemper concluded.

Meanwhile, parents are already preparing for prolonged deliberations.

In case there’s another strike, Galarosa says that she is considering enrolling her two elementary school students in a before-school program so that her husband can drop them off at the same time as their child in middle school to ensure that he’s not late for work again. “I hope this is resolved very soon because this is impacting our lives,” she said.

mhellmann@seattleweekly.com

This story has been updated with information on the increase in absenteeism during the strike.