Rick Harlan stood in a corner of Benaroya Hall’s lobby Tuesday evening, strumming a ukulele and singing songs as Seattle educators formed a long line that snaked around the room. An instructional assistant at Leschi Elementary School, Harlan had adapted folk hymns to drum up morale as educators prepared to vote for a potential strike, the second one in three years.

“Solidarity forever, for the union makes us strong,” Harlan sung to the tune of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” “We went on strike three years ago and made them feel red heat. The district dared us once again to go out on the street. So today we rise united and again will not be beat,” he continued, punching his fist in the air.

Later that evening, thousands of union members voted to authorize a strike. Harlan’s sing-along will continue this upcoming school year if Seattle Education Association (SEA)—a union that represents 5,000 teachers and other school employees— doesn’t reach an agreement with the school district before classes resume on Sep. 5.

Prior to casting their votes, educators interviewed for this story expressed desires for increased pay, longer paid family leave, the rollout of an ethnic studies course throughout the district, healthcare for substitute teachers, and a reduced nurse and counselor to students ratio.

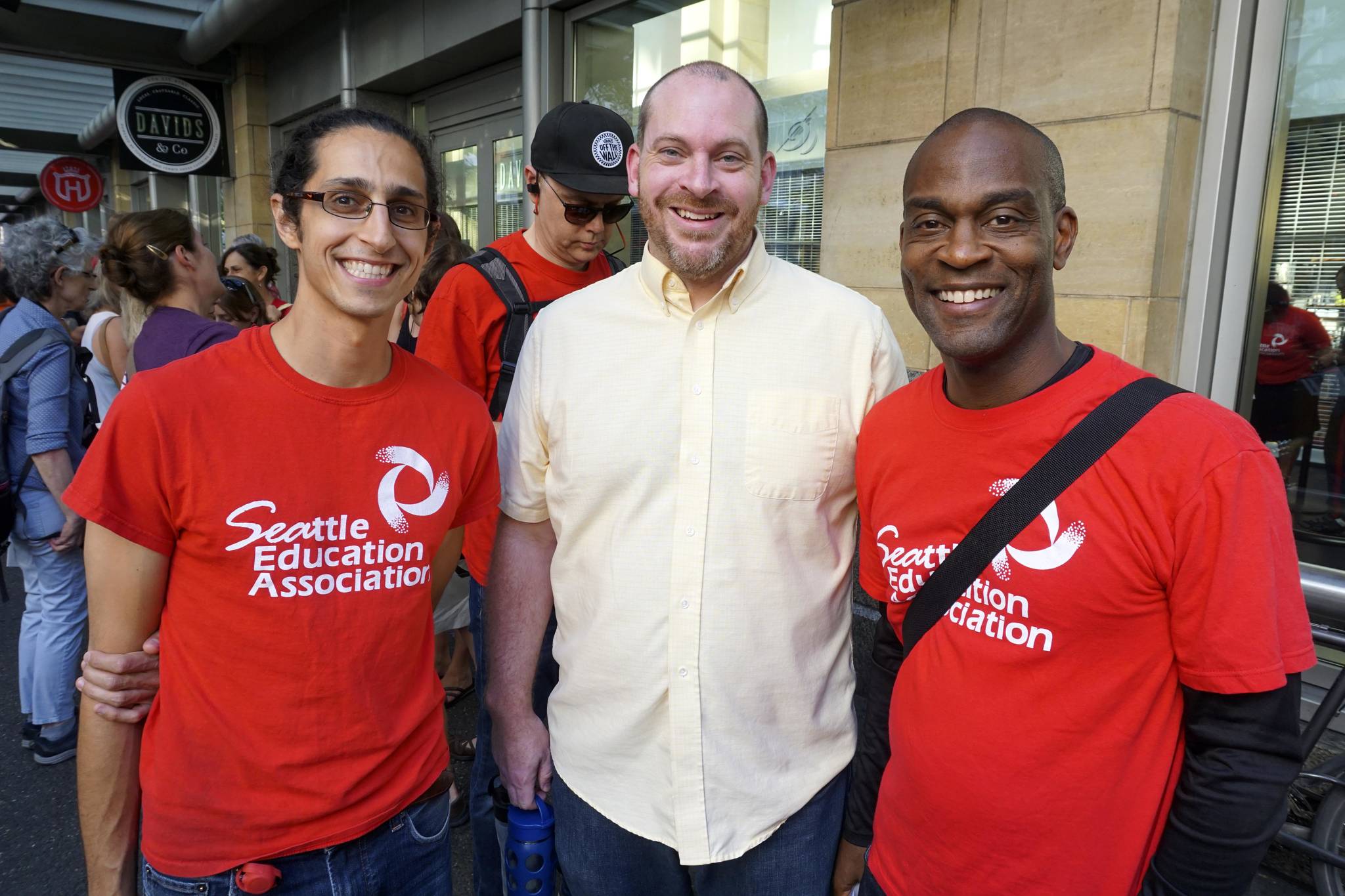

Seattle educators play music as others stand in line to check in for the vote to authorize an #SPSstrike, just three years after the last one. pic.twitter.com/8wB84vqkvn

— Melissa Hellmann (@M_Hellmann) August 29, 2018

District employees are seeking higher wages after state Legislators infused $776 million into the state budget for teacher salaries statewide to help settle a nearly decade-long legal battle called the McCleary decision. In 2012, the State Supreme Court found that the state was violating its constitution by underfunding the K-12 school system.

In an effort to end reliance on property taxes to fund basic education, lawmakers limited school districts’ ability to collect local education levy funding. Now the state will only allow SPS to collect $2,500 per student each year through the voter-approved local education levy, down from $4,000 in previous years.

Despite the increased funding for teacher salaries, SPS says that the decrease in revenue from local levies will lead to a deficit in upcoming years that could cost some staff their jobs. SEA, in contrast, argues that the state gave the districts enough money to increase educators wages, and that competitive salaries are needed to retain talented staff.

SEA is one of over 200 unions throughout the state in contract negotiations, according to statewide teachers’ union Washington Education Association (WEA) spokesperson Rich Wood. If an agreement is not made within the next week, Seattle teachers will join the ranks of striking educators in Washougal and Evergreen. Four districts in southwestern Washington have also postponed the first day of school or cancelled classes this week to picket at their campuses.

“The dozens of contract settlements in districts across the state prove that school districts have the money and opportunity to invest in competitive pay for teachers and support staff,” Wood wrote Seattle Weekly in an email. “School administrators have the money, now they need to invest it in great teachers and staff for our students.”

The outcome of a strike in Seattle could have ripple effects throughout Washington. “Seattle is the biggest district in the state. There’s a lot of smaller districts who are looking up to Seattle to see what Seattle will get so that they are in a better position to bargain,” Cynthia Nkeze, an english teacher at Seattle World School, told Seattle Weekly as she stood in Benaroya Hall’s lobby. “So Seattle cannot afford to fail those districts.”

Nkeze also fears that Seattle will lose talented teachers to surrounding districts if the union doesn’t secure a contract that reflects the city’s cost of living. “And that will leave the students of Seattle Public Schools in the classrooms, while the best teachers are elsewhere,” she said.

SPS teachers’ salaries range between $51,500 to $100,700 under the current contract, the district’s assistant superintendent for business and finance, JoLynn Berge, told Seattle Weekly in an Aug. 6 interview. Meanwhile, teachers on Bainbridge Island negotiated a 21.2 percent wage increase to earn between $53,905 and $105,096; Shoreline’s union also secured salaries ranging from $62,088 to $120,234 through a 24.2 percent wage increase, according to WEA data.

SPS officials declined to provide negotiation details during bargaining, but the district’s website noted that formal bargaining with the union will resume Wednesday morning. “We believe we are making good progress and will continue to work out compensation details as we face a very difficult financial situation,” SPS officials wrote in an email to Seattle Weekly.

In the district’s eyes, the state lawmakers’ plan wreaked financial havoc on Seattle, causing a projected budget shortfall of $43.8 million in the 2019-2020 school year, $55.7 million the following year, and $68.1 million in the 2021-2022 school year. In order to fund teacher salary increases, the district “will need to make reductions across the organization including staff and student services and programs,” SPS officials wrote.

Despite the district’s projected financial woes, educators preparing to vote at Benaroya Hall on Tuesday expressed dismay that they would need to go on strike again, just three years after the last one. In 2015, Seattle teachers picketed for five days following stalled contract negotiations. The city’s first systemwide strike in three decades concluded with an agreement on guaranteed recess for all Seattle elementary school students and the first cost-of-living raises for teachers in over five years.

Darryl James, a school counselor for Licton Springs K-8 School, hopes for similar outcomes in this year’s potential strike. Along with salary increases, James would like the contract to include a lowered counselor to student ratio. Although he only helps 180 students in his school, James said that the average counselor in the district sees up to 420 students. Such high caseloads result in the counselors being inaccessible to students in need. “The problem is that you won’t be able to see certain students, so you have kids who might end up not coming down to the counselor’s office because they know you won’t be able to see them,” James said.

Robert Eagle Staff Middle School speech language pathologist Judson Kane stood beside James in line, stroking his young daughter’s hair as he discussed the difficulties of living in Seattle on an educators’ salary as a single parent with exorbitant student loans. “I don’t have money to pay for childcare,” Kane said. “It would be between me coming, or not coming,” he said about his decision to bring his daughter to the meeting.

High caseloads also plague special education teachers like Westwoodland Elementary School’s Courtney Butorac, who said that her workload has increased to 14 students—four more than the current contract’s limit. “My student’s require a lot of support—that’s why they’re in my program. But the more students we get, the less time we can devote to each child,” Butorac said.

She recently bought a home in Beacon Hill, which she said has made it even more difficult to make ends meet on her salary. “We’re drowning in bills and house payments, and trying to keep ourselves afloat. And to know that I could just go across the water … and get paid more in Bellevue.”

Although Butorac said that she is committed to remaining in Seattle, she’s heard other teachers express a desire to move to neighboring districts.

According to the district’s budget update in early August, staff reduction in upcoming years may be inevitable. Yet SPS officials maintain that they are seeking a resolution before classes commence.

“Seattle Public Schools values and supports our educators and believe they deserve a fair and competitive salary that includes every dollar the state has provided for compensation,” SPS officials wrote Seattle Weekly in an email. “The joint SEA and SPS teams are working really hard towards a positive resolution. We remain optimistic that school will begin on time.”

mhellmann@seattleweekly.com

: