“Ladies, let’s hear it for Will Ryder!”

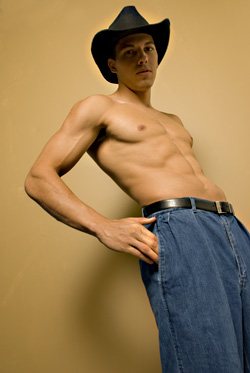

A gaggle of frenzied women hoot and clap as Ryder, a dancer at Centerfolds, the only all-male strip club in Seattle, strides toward a solitary silver pole to the opening strains of a Kid Rock song (“Cowboy… cowboy…”). As layers of clothing come off, the women get frenetic, pawing at Ryder as he works the crowd, picking up tips. Within a couple of songs, he’s back on the stage—only a crumpled cowboy hat stands between the audience and his birthday suit.

Ryder pumps at the air and, after allowing a couple of peeks at the family jewels, takes his bow. “That was Will Ryder,” the MC says. “Lap dances are $10, ladies.”

Centerfolds Inc. began operating under an adult-entertainment license in 1995, according to Katherine Schubert-Knapp with the city’s Executive Administration Department. In so doing, its owner, Mark Overton, snagged one of only five adult-cabaret licenses allowed under a moratorium the city maintained for more than 18 years, before U.S. District Judge James Robart struck it down in September 2005, finding “that the City’s current licensing scheme is unconstitutional.” (The moratorium wasn’t formally lifted until last June.)

But without a serious cash injection, bachelorettes in Seattle may have to look for other ways to get in a last hurrah of wanton debauchery before settling down, as Overton has struggled to keep the business afloat.

Since 1994, the state departments of Revenue, Labor and Industries, and Employment Security have filed 27 tax warrants for unpaid taxes against Overton and Centerfolds, according to King County Superior Court records. Department of Revenue spokesperson Mike Gowrylow says warrants are only filed after extensive attempts to reach the owner. But despite such efforts, the department still files about 5,000 per year. “Unfortunately, it’s fairly common,” says Gowrylow.

In many cases, the warrant is enough to get people to pay the bill; and for a while, Overton was no exception, usually taking care of the total shortly after the issue showed up in court. Except in 2004, when a warrant was filed for $11,680. That warrant is still outstanding, Gowrylow says, although he concedes it is possible that Overton has been making installment payments, which would not show up in court documents.

That 2004 warrant is significant for Overton because, two years earlier, he dissolved Centerfolds as a corporation and obtained a new license as a sole proprietor. Under that designation, Overton is personally responsible for any debts incurred by Centerfolds. Gowrylow says some people choose the sole-proprietor route to avoid the costs associated with incorporation. Overton’s corporation was maintained by attorney John Hess, who was disbarred in 2001 for legal malpractice, one year before Overton became a sole proprietor.

Overton has a history of getting himself entwined in financial snafus. In 2004, he was evicted from his Federal Way home. Overton claimed that he had entered into an agreement to eventually buy the house he was living in and had been overpaying the rent, but the landlords claimed he owed them $2,100. The financial issue was eventually resolved, but Overton pursued an additional claim that he was the rightful title holder of the Federal Way home. The judge ruled against Overton on his claim of a right to ownership last February, writing: “Plaintiff Overton indicated he would be earning money from various enterprises to purchase the property, but those funds never materialized and his expressed intent to purchase the property never became a reality.”

Furthermore, in 2006, Overton was sent to collections by a San Diego–based company, Transwestern Publishing Co. LLC, for failing to pay for Centerfolds ads in phone directories. He never responded, and a judge granted Transwestern the right to collect $6,252.46 plus interest.

While Overton did not return repeated requests for comment, the traditionally good-looking (6-foot-2, tan, perfect teeth), 27-year-old Ryder talked about his experience at Centerfolds over a mint mocha at a downtown coffee shop, dressed in an orange sweater and brown slacks.

The Pacific Lutheran University graphic design grad was fired from a job in retail and looking for something to pay the bills while he interviewed for more traditional daytime employment. “I was thinking, ‘Well, if girls can do it, why not a guy?'” he says of his decision to pursue a career in exotic dancing.

He landed an audition at Centerfolds, and started working the door that night. The next day, he got his adult-entertainer license and started working the stage. Ryder says he makes up to $300 a night. And despite the occasional rowdy customer—one woman took a bite out of his backside—he isn’t looking to get out of the business any time soon.

“It’s more money than a regular job,” Ryder says. “And I’m having fun doing it.”

But the dancers are all independent contractors, so their success does not necessarily reflect Centerfolds’ revenue. Overton makes his money from the $17 cover charge. The only men at Centerfolds are the ones taking their clothes off. And per their contract, the dancers pay a house fee and make all their money off tips.

Centerfolds’ hours also have been cut back. While some online club directories list the club as open seven nights a week, it is currently only open Fridays and Saturdays—though if there are requests from bachelorette parties, the club may also open on a Thursday.

And now, the very nature of the venue might be in for an overhaul. Last August, on one Centerfolds dancer’s MySpace page, Overton wrote: “Hey, LADIES and Gentalmen im [sic] looking for entertainers for my CLUB.”

Ryder says he has heard Overton might be looking to take Centerfolds in a more Vegas-style, coed revue direction, but didn’t want to speculate on what it might look like or when it might happen.

Even without the moratorium, there hasn’t been a rush to open new adult cabarets in Seattle, male or otherwise. Zoning severely limits the locations for new venues, and strip-club regulations in Seattle remain fairly stringent (for example, dancers must be on stages well removed from the audience by the time they drop trou). Since the moratorium was lifted, only one application for an adult-entertainment license has been filed, by local architect David Hasson, says Schubert-Knapp. According to city records, Hasson filed the application for Fantasy Unlimited on Westlake. A member of the Déjà Vu chain, Fantasy Unlimited provides patrons with adult-themed products and a live peep show, a designation that falls short of a strip-club license.

“We’re hoping within the next five months to be completed and open,” says Wendy, a manager who answered the phone but would not give her last name. She adds that because of the Déjà Vu connection, Fantasy Unlimited will operate in a similar format with female entertainers, but does not yet know if they will adopt the Déjà Vu name.

Otherwise, the lack of interest in new venues may be due in part to the reality that any nightclub willing to finesse the letter of the law can put on nearly the same show as Centerfolds, without succumbing to the rules that prohibit alcohol at full-fledged adult cabarets.

Capitol Hill’s R Place, for instance, hosts an amateur strip show with a $3 cover charge and a $200 cash prize for the winner every Thursday. Unlike Centerfolds, which can be pretty sparse if bachelorettes don’t show up, R Place’s third floor is packed by the time the show starts a little after midnight. The onlookers are mostly young gay men, but all types are welcome. Before the action begins, Hostess Lady Chablis, a matron of the Seattle drag scene, explains the no-touching rule, then yields the sound system to pulsing dance tunes.

The first amateur up is Mr. Ed, a paunchy guy who awkwardly gyrates down to a thong. Chablis laughingly dismisses him with “we’ve seen enough.” But the next contestant, Preston, is well built and has rhythm. As he works his way down, swinging around a pole, the distinctions between the entertainment at Centerfolds and R Place grow pretty narrow.

The Seattle Municipal Code is explicit about what defines adult entertainment: being “unclothed in such attire, costume or clothing as to expose to view any portion of the breast below the top of the areola or any portion of the pubic region, anus, buttocks, vulva or genitals.” At R Place, the skivvies stay on, though contestants occasionally skirt the law with a flash of a backside. For the women performing in burlesque shows at places like the Pink Door, a set of pasties is enough to stay in compliance. With these shows packing in fans, Centerfolds and Overton may struggle to expand their audience, even with a face-lift.

But Ryder isn’t worrying too much about the future right now. He’s been focusing on his characters, who, in addition to the cowboy, include a cop, a mechanic, and a disco dancer. His success, he says, is less about the sexual aspects of stripping than about putting on a good show.

“We don’t want it to be sleazy,” he insists. “We want this to be classy.”

href=”mailto:lonstot@seattleweekly.com”>lonstot@seattleweekly.com