On March 28, the day that President Donald Trump issued an executive order that aims to repeal a slew of Obama-era climate change policies, Environmental Protection Agency Region 10 staffers got a mass email from national administration staff. The subject line: “Our Big Day Today.”

That was confusing. “What do you mean, ‘Our Big Day’? Whose big day is this?” recalls former Region 10 EPA staffer Michael Cox, who spent more than 25 years at the agency and the past four years as a climate change adviser before sending a scathing letter to Administrator Scott Pruitt and retiring on March 31. Region 10 is headquartered in Seattle, and serves Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and 271 Native Tribes. “I remember people reading it,” he says, and all around the office, “I could just hear the ‘Oh my gosh, is this a joke? Is this an Onion thing?’” To Cox, it utterly defied reason that anyone at the agency at any level “could truly think they could send a message [about the executive order] saying ‘Our Big Day,’ implying that we should be joyful.” In reality, he felt, it was more like being “flipped the bird” and told “we’re here to dismantle you guys.”

Though it wasn’t the first disorienting or demoralizing moment for the agency (or for Cox) since Election Day, that email “sent me and many others over the edge,” he says. Until then, “we had hope” that the climate-change skepticism and anti-environmental-regulation rhetoric at the helm of both the White House and the EPA wouldn’t take things too far. “This kind of put a damper on that.” Instead, it had become clear that “these people don’t really understand, or care, about EPA staff or employees, one. And two, they’re just incompetent.”

Cox can speak openly now that he no longer works for the agency, but a current staffer at Region 10 EPA who spoke on condition of anonymity confirmed that emotions are still running high in the department these days.

“This is an agency full of scientists and attorneys,” the staffer says. “You can imagine the depression, the upset, the concern – the wide range” of emotions following Trump’s election, given how strongly the President had railed against environmental regulations and dismissed the veracity of climate science during his campaign.

There was some hope after the election that Trump’s campaign rhetoric was mostly talk, but then he named Scott Pruitt the head of the EPA. “At that point,” the staffer says, “it was sort of a collective, ‘Ahhh, fuck.’” The new administrator had built a career off of suing the very agency he was now asked to lead. Over the next few months, Region 10 employees looked “for glimpses of hope, and at every turn, [Trump and Pruitt] have done what one would unfortunately expect them to do.” The clearest effort so far on the part of the new administration to downsize the agency is a June 1 memo declaring its intention to “realign our workforce to meet changing mission requirements” through voluntary buyouts or early retirements. Trump’s budget, if enacted, would slash the total number of EPA employees from about 15,000 to about 11,500.

To Cox, this is a way the administration can start moving in the direction of major cuts in advance of any clear directives from Congress. “The agency has every right to do that,” he says. “They can go and ask for buyouts and try to get attrition that way.”

But former EPA Region 10 Administrator Dennis McLerran, an Obama appointee who left his position on Inauguration Day, says these efforts are “rather presumptive… The President does not yet have a budget, but they’re acting like… there is going to be a significant reduction in staffing and resources. Congress actually controls the power of the purse and is going to have a strong say in that.”

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has “certainly created an atmosphere [at the EPA] where people are hesitant to bark back,” the Region 10 staffer says. “And maybe that’s the smartest thing they can do, just create that atmosphere… so [EPA employees] just hunker down and say, ‘Well, this too shall pass.’”

But when Trump pulled out of the Paris climate agreement, and Pruitt followed the president’s announcement with a press conference during which he dodged the question of climate change over and over, that marked a serious change, the staffer says. Now, “I think there’s an increasing amount of ‘fuck you,’ I will say that. … Pruitt really blew it.”

These feelings are not likely unique to this particular Region 10 staffer; chances are high they’re shared by the vast majority of the 15,000 people who currently work for the EPA anywhere in the country. And while the staffer suggests that EPA employees will be inclined to leak the most draconian federal directives to the public — and possibly orchestrate some kind of internal revolt — the most concrete form of resistance from within right now is simply to do their jobs as best they can.

“People can’t just sit on their hands for years; they’ll go crazy. That’s not the people I know,” says Cox. “Many of them are going to keep pushing until they’re told not to. … The last couple of weeks I was there, I put on two climate change workshops. I kept pushing. I’m going: ‘We’re gonna do this. I don’t care.’…. My advice to friends [still at the EPA] is just keep going. Make them say no.”

Another mild form of internal resistance, Cox says, would be for EPA staff to inform EPA partners, like states and tribes, of the specific effects that certain program cuts would have on them, and encourage them to agitate about it. “Just to say, you know, if this money is cut, we’re not going to be able to do X and Y,” Cox says. “Just facts.”

Like Cox, other ex-employees of the EPA — including a national coalition of former EPA employees calling themselves the Environmental Protection Network — have spoken out in recent months. Last Monday, for instance, that group released a withering analysis of the proposed EPA budget’s effect on scientific research.

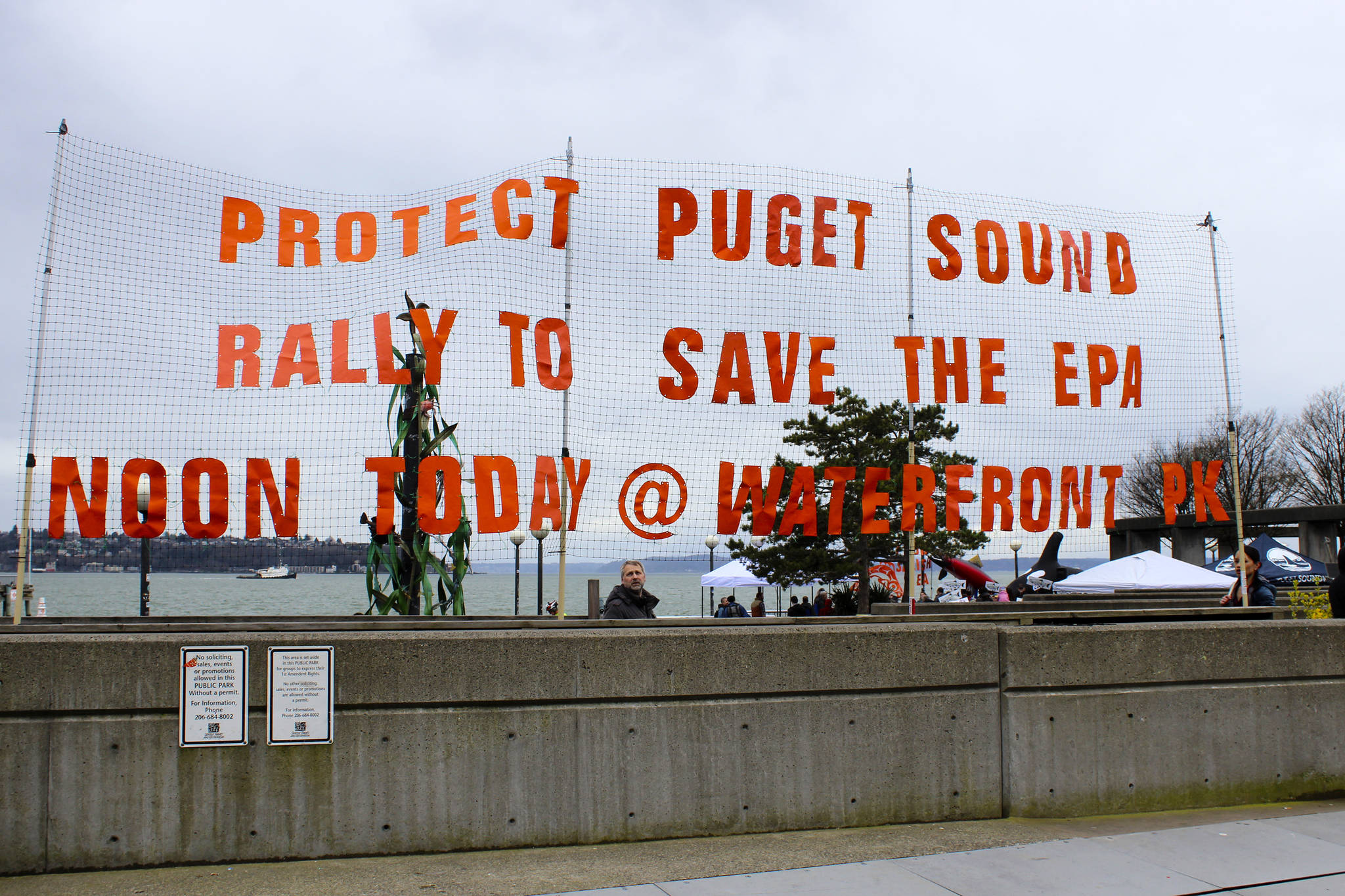

All three current and former EPA staffers Seattle Weekly spoke to for this story emphasized that we shouldn’t worry about the Duwamish Superfund site. The EPA has already done the heavy lifting on forming a cleanup plan, and it shouldn’t be at risk of derailing. Region 10 efforts most at risk with a weakened EPA, they say, include long-running collaborative projects to restore salmon habitats and to improve the health of riparian corridors (the land alongside rivers and streams) — some of which have been developed through long, painstaking communication among famers, tribes, and local governments, and are finally ready to go and just need a bit of funding to kick them into gear. There are also concerns that there will be no climate change research budget to speak of; a drastrically reduced pollution-violation enforcement budget; and, among many other things, zero dollars for Puget Sound.

But perhaps among the most affected would be Native tribes. Region 10 includes more tribes than any other EPA region, says the staffer. “Half the tribes in the country are here in Region 10… That’s an enormous concern for us.” Trump’s proposed budget eliminates all funding to EPA programs that support Native villages in Alaska, including one that helps install and maintain safe drinking water and sewage systems. The staffer adds, angrily, that the proposal to cut that funding — not to mention the myriad grants to Native tribes that federal EPA dollars provide— is a way to “continue to hose people that [the U.S.] has hosed for 200-plus years.”

Cox, McLerran, and the Region 10 staffer all agree that Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski will not stand for that, in the slightest.

Which brings them a key point that begs repeating: When it comes to the budget and staffing, it’s Congress that has the final say, not the president. Of note is that in 2008, the EPA’s budget was $7.5 billion with about 17,000 staff; by 2017, the total number of employees had fallen to about 15,000, thanks in part to GOP-led cuts. Similarly, in Region 10, there were about 600 employees prior to the Obama Administration and about 500 now.

Not to say that there aren’t fears – tears, hand-wringing, fearing for one’s job or program – but a 31 percent budget cut, the largest slash Trump proposed for any federal agency, “while shocking …. [is] just bad politics,” the Region 10 staffer says. “People dig clean water. We’re quirky that way.”

It does seem that this EPA budget is extremely unlikely to pass Congress as planned. Pruitt’s first attempt to defend it in front of the House Appropriations Committee last Thursday signified as much. “I can assure you you’re going to be the first EPA administrator that’s come before this committee in eight years that actually gets more money than they asked for,” said Rep. Tom Cole, a Republican Congressman from Oklahoma who’s worked closely with Pruitt in the past.

McLerran adds that he believes the courts will side with environmental laws, too. EPA rules — including, for example, the 2009 endangerment finding, a court-backed rule that states that greenhouse gases threaten public health and welfare — are based in science and data and facts, and courts care about that. McLerran believes the same logic applies to the Clean Water Rule — another rule at the butt of a Trump executive order — or any EPA rule. All the hand-wringing around the executive orders, the rhetorical pronouncements, and the proposed budget ignores procedural requirements under the federal Administrative Procedures Act.

“If you’re going to withdraw a rule and propose an alternate,” he says, “you have to have a fact base for that.” He adds that the language in each anti-environmental-regulation executive order is couched in “’reconsidering’ and ‘reviewing.’ They’re smart enough to have lawyers in the room to tell them that you can’t just say you’re going to abandon [the rules]. They’re going to reconsider it; they’re going to review it… You can’t do that arbitrarily. You’ve got to do that with the proper procedures and the proper findings and the proper process. If you don’t, that’s ripe for a legal challenge.”

Still, McLerran says, “it’s all very concerning because it’s setting a direction, it’s setting a tone. It’s definitely trying to reverse 40-plus years of progress in implementing these statutes driven by science and driven by data… It shows that elections have consequences.”

The Region 10 staffer agrees, adding that the administration’s actions have consequences, too. The exit from the Paris Agreement and its subsequent press conference was “a huge miscalculation on Pruitt’s part. He’s likely lost any ability to get the career staff at the agency to do what needs to get done for his agenda.”

While “morale is pretty low, no doubt about it,” the staffer says, “if I know people at the EPA, we’ve gone from being resigned… to ‘They’re not going to get away with this.’ This shit is on.”

sbernard@seattleweekly.com