Ryan Leaf, the pride and shame of Washington State University football, didn’t take many snaps in the NFL. But he took a few more than he probably should have thanks to painkillers.

As Leaf’s life spiraled into post-career drug-addicted chaos, he would recall a time, while playing for the San Diego Chargers, that he suited up with a broken wrist. To make this bearable, he did what many NFL players had done before him—popped a pill, killed the pain, made it through another game.

In a way—and more so with every passing season—Leaf’s ill-advised game-day coping mechanism is analogous to the one employed by millions of NFL fans. It seems that no matter what we may have heard about football’s dire effects on the brains of the men who play it—the stammers, the inability to remember where they are, the suicide-inducing debilitation—come kickoff, we numb ourselves to these facts in order to make it through four heart-pounding quarters. Just as Leaf used pain pills to deceive his body into thinking it was fit to be on a field, we pop tortured rationalizations to deceive our consciences into thinking that our viewership has no bearing on the brutality we are viewing—“They’d play whether we watched or not” or “They chose to be on the field” or “The league is dealing with it.”

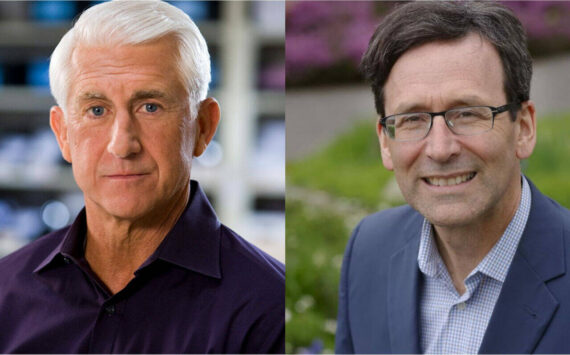

Yet complicit as all football fans are in this mass deception, few seem to occupy a more rationally tenuous place than Paul G. Allen, owner of both the NFL’s Seahawks and a brain-research institute.

For all the good work Allen has done through the Allen Institute for Brain Science, he’s been notably shifty about football brain trauma in the few opportunities reporters have had to ask him about his two seemingly divergent passions.

Speaking to The Seattle Times a few years ago, Allen seemed to take a “let-the-league decide” approach. Addressing a brutal hit on wide receiver Percy Harvin, he said that while he personally might think the player who leveled Harvin should have been penalized more than 15 yards, ultimately it’s “for the league to evaluate and figure out in the future.”

Elsewhere, he’s pointed to the brain research he’s helping fund while deftly not acknowledging the problem that’s prompting the research. “We’ve talked extensively with the league about the kind of research that should be done and that we want to do,” he told Forbes in 2014. “You can have concussions and trauma from all sorts of things, like IEDs in Iraq and motorcycle accidents. We’re going to look at some of this tissue and see how it differs from some of the tissue we’ve already scanned and have in our data banks.”

While we can’t say for sure, Allen’s equivocations on the subject were likely related to the fact that the NFL itself, which answers to team owners like Allen, had never acknowledged a connection between football and the degenerative brain conditions that many former players say have plagued them. But that changed this week, and it’s now time for Allen to be more forthright about the effect football is having on the minds of its players and to become the leader on the subject he is in the perfect position to be.

On Monday, the league, for the first time ever, officially acknowledged a connection between football and the neurological condition known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. In Washington, D.C., U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.—no doubt a Bears fan) asked Jeff Miller, the NFL’s senior vice president for health and safety, whether CTE and football had been linked.

“The answer to that question is certainly yes,” Miller said.

That response contradicted comments made by NFL officials as recently as Super Bowl Sunday, ESPN reports.

To a passive observer, this may just seem like a matter of semantics. After all, the NFL for years has been taking steps to address brain injury on the field without fully acknowledging the underlying problem. To the chagrin of some fans, helmet-to-helmet hits have been outlawed, and a nasty hit on the quarterback is liable to cost you 15 yards.

Yet as Schakowsky noted, the NFL has been subjecting its fans to subtle deception, aiding in their rationalization.

“The NFL is peddling a false sense of security,” Schakowsky told ESPN. “Football is a high-risk sport because of the routine hits, not just diagnosable concussions. What the American public needs now is honesty about the health risks and clearly more research.”

Honesty and research: Paul Allen is already providing the latter. Now he should provide the former. Because as a WSU alum himself, he knows that the Ryan Leaf approach to life is not sustainable in the long run.

Seattle Weekly delivers a fresh perspective on Seattle news and culture every week. Love it or hate it, let us know at editorial@seattleweekly.com. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. And get a new editorial every week by subscribing to our weekly newsletter.