THE SUSPECT acted erratically, had earlier displayed a gun, and lunged at him, the Seattle cop said. The officer feared for his safety. He fired once at close range. The suspect fell dead.

That’s the scenario of the controversial police shooting of David J. Walker, 40, slain by Seattle police officer Tom Doran near Seattle Center last month. Allegedly firing a gun after a shoplifting incident, Walker was brandishing a knife when he later made what police termed “a lunge” at pursuing officers. While raising his empty hand in the air, he was fatally shot in the chest.

But that’s also similar to what happened last July when Seattle police officer Carl Chilo shot and killed a man named Michael J. Okarma in South Park. An inquest jury later concluded Chilo acted in self defense after Okarma “lunged” at the officer.

The little-noticed shooting was ruled justified, even though the officer shot Okarma in the back of the head.

The similarities of the two killings—as well as some striking differences—raise challenging questions not only about the shootings, but also about the prosecutor’s and community’s reactions to them.

Walker was black and the cop who shot him is white, again underscoring the role race plays in police shootings. Of 33 people who died at the hands of Seattle police—shot or choked—since 1980, 19 were white and 14 were minorities. At least two protests have raised the issue of whether Walker would have been killed if he had been white.

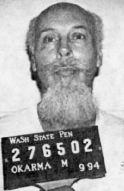

Okarma, however, was white. And the cop who shot him is black. According to coroner’s inquest records, Chilo was making what he called a routine 6am residential checkup on Okarma, a registered sex offender. The officer says Okarma, preparing to head off to work in his truck, pulled a gun after Chilo asked for ID. A struggle ensued. Okarma dropped his gun. Chilo pulled his and killed the 56-year-old laborer.

The shooting got only brief mention in the news media and the outcome of Okarma’s inquest has gone unreported until now. There was no community outcry over the killing, described in daily newspaper reports as the shooting of an armed suspect who had a long record (Okarma was sentenced to 10 years after pleading guilty to second-degree rape and possession of stolen property 18 years ago; he also did three more months for parole violation).

There was no widespread debate over why an ex-con who had not reoffended since his 1994 release would pull a gun on his way to work and attempt to kill an officer who had asked him for ID. Police found Okarma’s ID at the scene of the death, along with two guns belonging to the ex-con. (Possession of firearms is illegal for a convicted felon.)

Most startling, unlike Walker who was shot in the chest, Okarma was struck by one bullet in the back of the head, from a range of two feet or less.

THE QUESTION in the Walker case is whether police were justified in shooting a man armed with a knife. In Okarma’s case, was there justification for shooting a suspect from behind at close range, after he had dropped his gun? And was that how it happened?

“Our expert told us,” says Seattle attorney Tony Savage, who represented Okarma’s family at the December inquest, “the officer was hanging onto Mr. Okarma’s wrist when he shot him in the back of the head.”

Walker was shot as TV cameras caught the action, but Okarma was shot in an otherwise deserted alley. Records show Chilo claimed Okarma was stalling while looking for his ID. The officer said he opened Okarma’s truck door, Okarma stepped out with a gun, and the two of them began fighting. Chilo recalled, “I mentally prepared myself to be shot.” In the struggle, Okarma’s gun fell to the ground, according to the officer. Chilo, a six-year veteran, testified he was able to draw his gun, knock Okarma away, and shoot him in the head. “I attempted to check for a pulse on Okarma but my hands were shaking too much to feel anything,” Chilo said.

Unlike the Walker case, where a review of the news video can provide balance, evidence in the Okarma inquest was presented mostly by the officer—represented by an attorney—and his fellow officers who investigated the shooting.

Theoretically, the prosecutor is a neutral presenter of inquest facts and evidence. “Whichever way you feel,” Mark Larson, chief criminal deputy, said last year, “the inquest can help answer your questions. That’s the triumph of the system.”

However, in the Okarma case the prosecutor’s office fought against attorney Savage’s presentation of expert testimony that contradicted the police officer. District Court Judge Darcy Goodman went along with the prosecutor’s request to suppress the testimony. Ironically, the expert was Kay Sweeney, a 33-year veteran of police forensics now in private practice, who had served as the prosecutor’s own expert in the past. A report Sweeney prepared notes that the Okarma “shooting could not have occurred in the manner the officer asserts.”

“If you can’t get your expert to testify,” says Okarma’s sister, Lee Rees, who is also an attorney, “I don’t see where that supposed fairness exists in this system.”

While both she and Savage agree that Okarma had a violent past, the bigger issue was whether the inquest was a balanced attempt to find the truth. That question looms anew in the upcoming Walker inquest. Does a system that has not found a police killing unjustified in 20 years so favor law enforcement that it serves no legitimate purpose?

“All they had to do was tell the jury it was cop versus predator,” says Rees, referring to the Okarma jury, “and they were sold. Just another criminal down the tube.”

“Generally, at inquests, you don’t have sympathetic victims, and that was certainly the case here. But after sitting through four days of hearings, I still can’t tell you why my brother was at one moment going to work and the next lying dead on the ground. Nor can anyone else.”

Read Rick Anderson’s License to kill.